In 1971, when there were few employment opportunities for geography students beyond the classroom, Greg Babinski graduated from Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan, with a bachelor’s degree in geography. One of his teachers was William Bunge, who contributed to the understanding and application of quantitative geography. This research was later further developed with the expanded use of GIS technology. “Influenced by the social unrest of the 1960s, Bunge became a political radical,” says Babinski, “but he had great insight into the power of spatial analysis for social justice.”

Babinski decided to continue his education at Wayne State and earned his master’s degree in geography in 1977. Upon graduation, Babinski went to work as a drafting technician for the Michigan Wisconsin Pipeline Company before moving to California. He worked on the Prudhoe Bay Oilfield project for the Sohio Construction Company and later worked for Johnson Loft Engineers, where he oversaw computer-aided design (CAD) work. “Using CAD provided me with the opportunity to better understand how computer-based design and mapping could be best applied in the real world,” says Babinski.

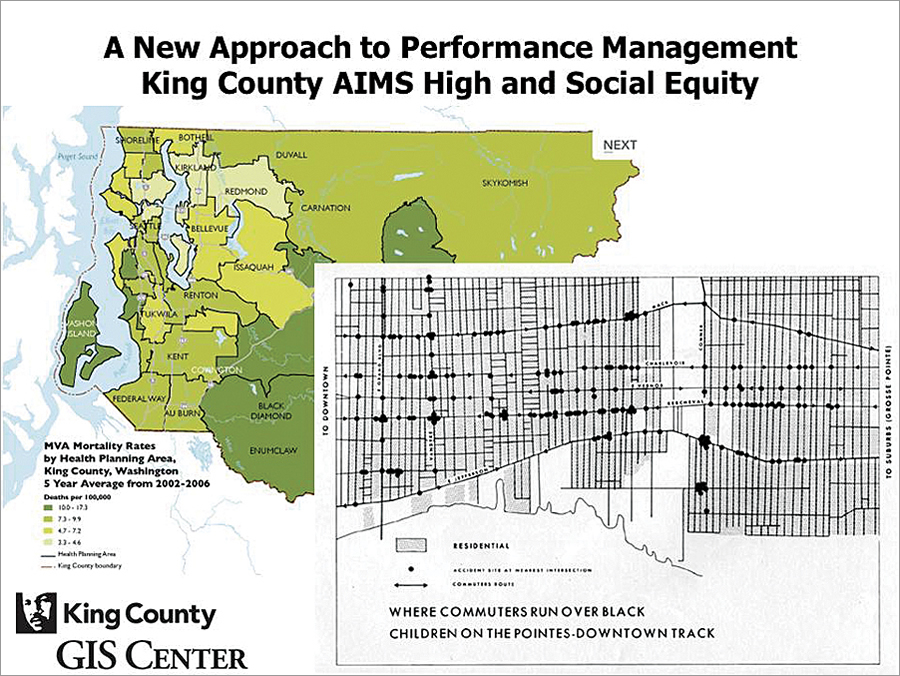

In 1989, Babinski went to work for the East Bay Municipal Utility District in Oakland, California, as the GIS mapping supervisor and began his lifelong affair with GIS. For the past 15 years, he has worked as the finance and marketing manager for the King County GIS Center in Washington State.

The King County GIS Center is set up as an internal service fund within the county. “This allows us to control our own budget,” says Babinski, “but also means that we have to pay our own way. We rent office space from the county and purchase our own equipment and materials, as well as pay for network services, and so on.” A key part of Babinski’s job is to explain the benefits of using GIS to other county divisions and how it would fit into their workflows and support their business models. “The center is steward of hundreds and hundreds of datasets and data layers, and we can help county agencies make better use of them for mapping, applications, and analysis,” says Babinski. “The business advantage is that we can help these agencies see their data differently, which allows them to use it more productively.” Because agencies understand the business benefits, Babinski has developed a GIS funding model based on objective usage metrics that provides financial support from 35 county agencies, as well as external customers. “It is important for GIS managers to show their customers the connection between their financial support and the benefits and services that GIS provides,” says Babinski.

The GIS center has three primary business lines, including enterprise operations for data management and system maintenance, matrix staffing for special long-term projects and programs, and client services in which the center acts as a consulting service.

Ultimately, the client services section developed into the county’s GIS Services Express, which provides regional agencies with targeted, low-cost help to get the most out of their use of GIS. Users can select from an extensive menu of services and products, including GIS data, mapping, web design, database support, training, programming, and GIS program support. “GIS Services Express is based on the service delivery model that has successfully supported distributed GIS activity in King County for many years,” says Babinski.

Babinski argues that the ultimate goal of the client services section should be to put itself out of business by encouraging GIS users in the county to make better use of GIS themselves so that they can reduce their costs and make their departments more self-sufficient. “I think that we should always be looking for opportunities to create simple GIS tools or applications or provide training,” says Babinski. “We will serve the county best by putting GIS tools in the hands of the end users.”

A few years ago, Babinski contacted Dr. Richard Zerbe, director of the University of Washington’s Benefit-Cost Analysis Center at the Evans School of Public Affairs, to determine the feasibility of conducting an analysis of the long-term cost benefit of an enterprise GIS in King County. Cofunded by the county and the State of Oregon, Zerbe and his associates studied the use of GIS by the county from 1992 until 2010 and determined that during that 18-year period, King County accrued net benefits of between $776 million and $1.7 billion, with costs totaling $200 million (see “King County Documents ROI of GIS“).

Building on the successful King County GIS cost-benefit study, Babinski would like to see a future GIS return on investment study of 10–15 cities throughout the United States and Canada to determine if those cities are experiencing similar financial benefits. “We’d be looking at return on investment, but we would also want to get other comparative information from each municipality,” says Babinski. “What are the components of their GIS? How is it organized? How’s it structured? What are the applications? What other technology are they using in conjunction with the GIS?”

Babinski’s interest in this outreach comes from his longtime involvement with the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA), a national organization of professionals who use GIS and other information technologies to solve challenges in state, regional, and local government agencies and departments. Babinski has served in various national leadership positions in URISA, including secretary; treasurer; and, most recently, president.

As president of URISA, Babinski promoted an initiative to attract more international members to the organization. At the moment, there is a URISA Caribbean chapter, as well as four chapters in Canada, and a new one in the United Arab Emirates. Babinski hopes that within the next 10 years, 50 percent of the membership will come from outside the United States. “I think that expanding the international scope of URISA will be beneficial to the entire membership,” says Babinski. “The organization is 50 years old, and we have much to share with those outside the United States. However, there is also a great deal that we can learn from those using GIS and other information system technologies in local government throughout the world. What are their challenges in implementing IT technology? How do they differ from our own? What are the similarities? I think there is a lot of opportunity for mutual benefit by extending our outreach internationally.”

Babinski recently announced the GIS Management Institute (GMI), a new initiative by URISA (see “Geospatial Society, the GIS Profession, and URISA’s GIS Management Institute“), at the 2012 Esri International User Conference. According to Babinski, “GMI will develop resources and services that focus on promoting the advancement of professional best practices and standards for the management of GIS operations.” The new initiative will begin by building on resources that URISA has already developed, including the GIS Capability Maturity Model (see “URISA Proposes a Local Government GIS Capability Maturity Model“), used to assess an organization’s ability to accomplish defined tasks, and the Geospatial Management Competency Model (GMCM). The GMCM specifies 74 essential competencies within 18 competency areas that characterize the work of most successful managers in the geospatial industry and is an element of the US Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration’s Competency Modeling initiative.

“I think that the future of GIS and of extending the concepts of geospatial thinking within society relies on professional standards-based education,” concludes Babinski. “Whether in formal university degree programs or through classes and initiatives supported by professional organizations, such as URISA, or for that matter, the GIS classes we conduct at the King County GIS Center, maps can help us better understand and analyze the relationship between seemingly unrelated things or events. And nothing gives me greater satisfaction than seeing the use of spatial analysis for social justice that Bunge pioneered being applied here at home in King County or worldwide via URISA’s GISCorps. After more than 40 years, for me, geography is still where it’s at!”

For more information, contact Greg Babinski, MA; GISP; finance and marketing manager, King County GIS Center; URISA GIS Management Institute Committee chair (tel.: 206-263-3753).