An organism with the sheer magnitude of an elephant—weighing up to roughly six tons—requires proportional amounts of space and resources for survival.

The elephants of Kenya’s Amboseli National Park ecosystem have always needed far more space than the relatively small, 242-square-mile (390-square-kilometer) reserve can provide. Amboseli elephants roam freely inside and outside the park, covering a broad swath of habitat at the foot of Mount Kilimanjaro that spans southern Kenya and traverses what, to them, is an invisible international border with Tanzania.

This landscape is changing rapidly, however. Increasing human populations and expanding development are putting pressure on available wildlife habitat. With humans consuming ever-larger shares of resources, elephant conservation is facing new challenges.

The Importance of Amboseli Elephants

Researchers with the Amboseli Trust for Elephants (ATE) have continuously monitored the Amboseli elephant population since 1972, when Dr. Cynthia Moss and Dr. Harvey Croze founded the Amboseli Elephant Research Project. Amboseli is unusual in that it is home to one of the few relatively undisturbed elephant populations left in Africa. As poaching to fuel the illegal ivory trade has made a comeback across much of the rest of the continent, the Amboseli elephants have been largely spared.

With an estimated 35,000 African elephants being lost to poaching annually, Amboseli’s elephant population has become increasingly valuable for understanding how these animals can navigate a changing landscape and adapt to increased human presence within their ranges.

A Rich History of Spatial Research

Documenting the spatial distribution of Amboseli elephants has been key since the project began. Every elephant sighting in the project database is associated with a one-kilometer square within a grid covering the study area, and sightings records since 1999 include a corresponding GPS point. In the early days, to define the full extent of elephant ranges and their movements in and out of the national park, researchers also fitted several elephants with radio collars; however, that technology provided such a limited amount of data relative to the risk of traumatizing the elephants while putting the collars on that their use was curbed.

In 2002, researchers used the GPS points, satellite imagery, and Esri software to perform GIS analysis on the study’s first 30 years of elephant location records. The results provided a clear, long-term picture of how elephant family units and independent adult males use the national park and how they change the location and size of their home ranges (the extent to which they move during the course of daily activities) over time. Fascinating patterns on both annual and seasonal scales emerged, but the vast majority of these sightings fell within the core study area inside and immediately adjacent to the national park itself—just a small fraction of the elephants’ total range.

Resurrecting Collar Tracking

To conduct research that addresses current knowledge gaps in elephant behavior, which could aid in creating informed conservation decisions for elephant populations that are less fortunate than Amboseli’s, ATE has increasingly turned to innovative geospatial tools. Modern satellite tracking collars can collect fine-scale temporal and spatial data, so investing in them is more practical now. These more accurate, longer-lasting collars can allow researchers to extrapolate major movement patterns for much of the elephant population by deploying tracking collars on just a few carefully selected individuals. That is because, although each elephant family has a unique strategy and pattern in how it utilizes the Amboseli ecosystem, the patchiness of resources, particularly water, means that different subsections of the population tend to make use of the same food and water sources, moving in similar geographic spaces.

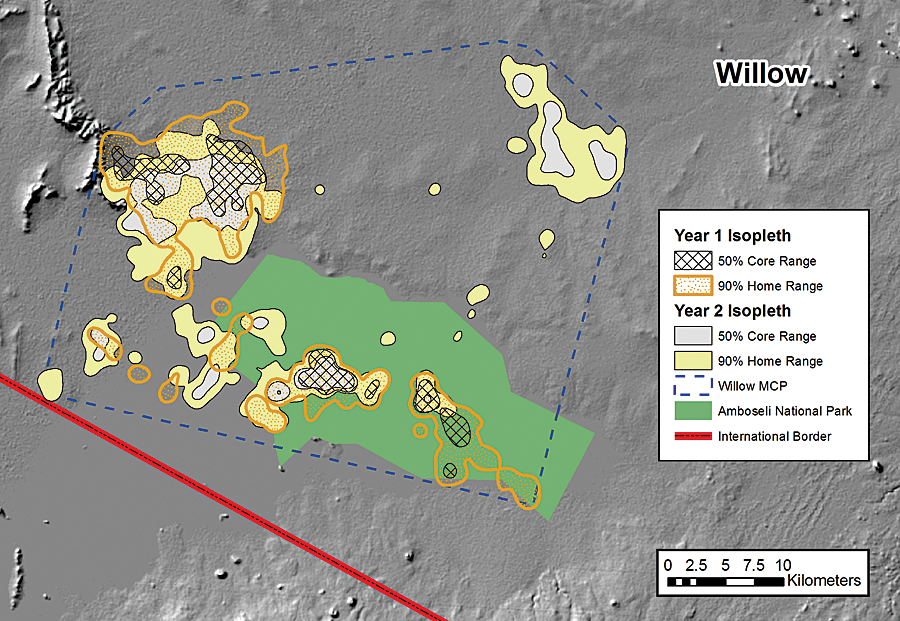

In 2011, ATE deployed five satellite collars on adult female elephants from different families around Amboseli. These individuals—known to researchers as Ida, Lobelia, Maureen, Vicky, and Willow—were chosen because, while their families roam in different areas from each other inside and outside the park, they are still illustrative of where other elephant families in their subgroups tend to go.

Over the following two years, these elephants’ collars recorded more than 78,000 GPS location points logged at hourly intervals. This wealth of data was analyzed using ArcGIS Spatial Analyst tools to investigate a variety of range metrics and movement parameters for the tracked individuals.

Developing a Deeper Understanding of Elephants’ Movements

The results provided valuable additions to the already detailed understanding of the population. We now know, for example, that elephants make seasonal movements to and from the permanent swamps in the core of Amboseli’s ecosystem in response to rainfall and available vegetation in outlying areas—a pattern that was detected in field observations and confirmed using the satellite collars. We also now have clear answers to questions that could not be easily explained using direct observations, such as which areas Willow and her family utilize during their long absences from the park; how far Maureen ranges into Tanzania; and what route Vicky uses to reach her feeding area north of the park.

The satellite collars also identified new patterns that may have otherwise gone undetected, suggesting new directions for further research. For instance, we now want to investigate why Ida and Lobelia, in the eastern part of the ecosystem, have smaller home ranges and spend more time inside the park than the individuals that use other areas. We are also curious about what caused Maureen to decrease the size of her home range and shift out of Tanzania in the second year.

The kinds of spatial datasets obtained with satellite tracking collars can provide insights into elephant behavior as well. One important focus of our current research is understanding how elephants perceive and respond to the risks associated with living in close proximity to humans. Analyses done using ArcGIS have shown that Amboseli elephants increase their travel speed while moving through human-populated areas and that they avoid these places altogether during daylight hours. The data has also confirmed the locations of frequently used habitat areas and corridors where elephants move long distances, which can help with conservation planning by identifying places that need additional monitoring resources and protection.

The results of this project, along with the outcomes of future collaring operations, will help guide ATE and other stakeholders in securing space for all of Amboseli’s wildlife. Ultimately, we want the future of the Amboseli ecosystem to be one of peaceful coexistence between humans and elephants for generations to come.

Visit ATE at elephanttrust.org or email info@elephanttrust.org to get more information.