A Michigan man is doing hard time after GIS was used to map GPS coordinates from his cell phone, placing him at the scene of a horrific crime: the fatal shooting of a 30-year-old woman who was accidentally caught up in a drug deal gone bad.

Karl Cotton, Jr., was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison in 2013 for killing Jamie Powell of Walker, Michigan. The conviction hinged in part on Cotton’s cell phone location information, which the Kent County, Michigan, GIS team mapped using Esri ArcGIS.

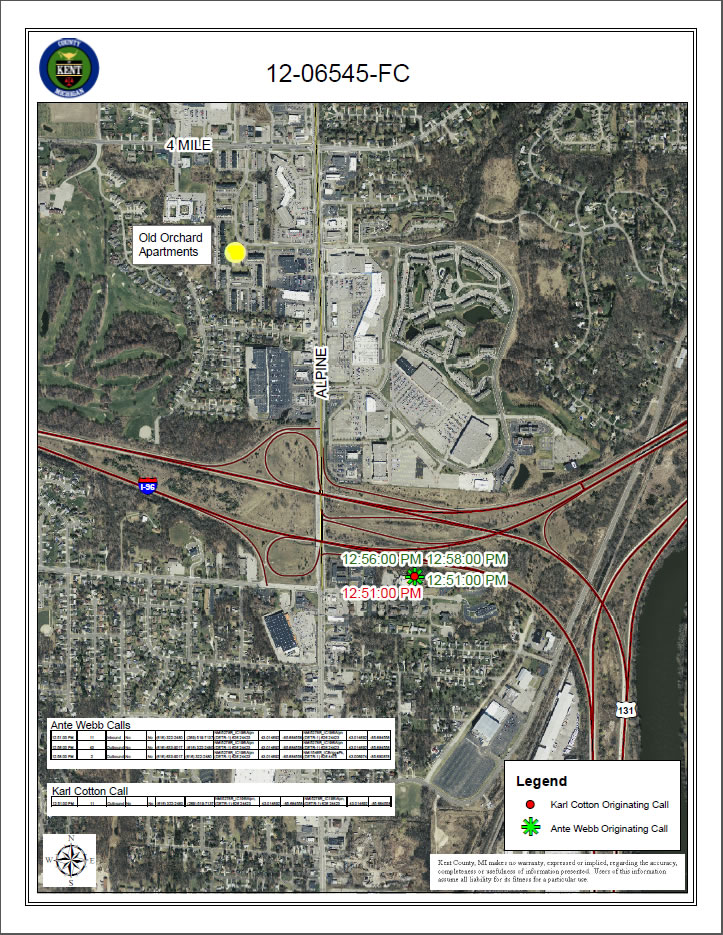

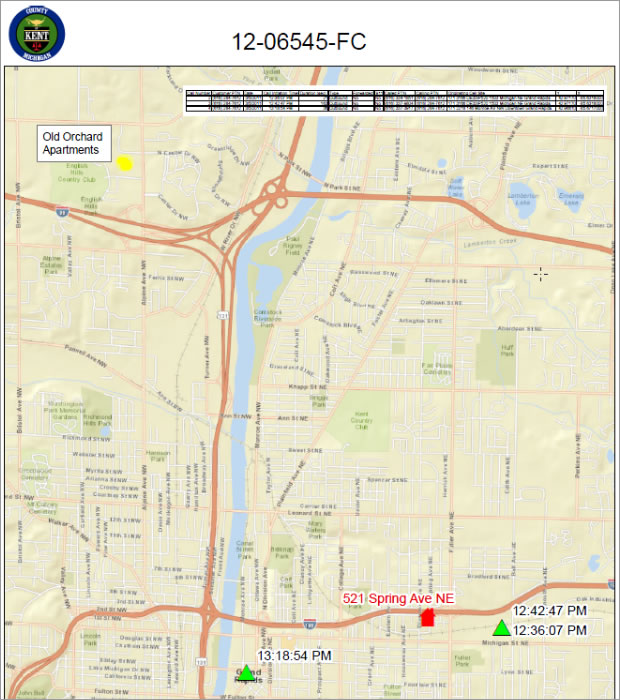

The maps, which were entered as evidence at Cotton’s trial, were made by the Kent County, Michigan, GIS department. They showed that Cotton’s cell phone records placed him close to the apartment where and when the murder occurred. The mapped locations of the other suspects in the case showed they were much further away.

No Physical Evidence

Robin Eslinger, assistant prosecuting attorney for Kent County, turned to GIS after being handed the 2011 murder case, in which there was no direct evidence such as DNA. Lead detectives believed that Cotton, a felon with a long rap sheet, killed the victim, Powell, after Cotton was robbed of $5,000 by one of Powell’s acquaintances during a botched drug deal in Powell’s apartment. The acquaintance fled through a bedroom window after allegedly stealing Cotton’s money. Police contended that Cotton blamed Powell for being an accomplice to the theft, fatally shooting her. Investigators believe Powell had no knowledge of any robbery or drug deal plans that day.

A lack of physical evidence in a murder case can be the bane of a prosecutor’s existence. Without a “smoking gun,” compelling circumstantial proof is needed to convince a jury of a suspect’s guilt. In the absence of direct evidence, prosecutors are learning that visualization methods, such as mapping raw GPS data, can be as useful as DNA in narrowing down a suspect pool.

The murder case was unusual. No useful fingerprints were found at the crime scene, and an exhaustive search of Powell’s apartment yielded none of the suspect’s DNA. To successfully prosecute Cotton, Eslinger would need to gather facts that would implicate Cotton beyond any reasonable doubt. That’s when one of Eslinger’s colleagues suggested contacting the county GIS department to create maps to build her argument that Cotton had committed the murder.

New Cell Phone and Number

Cotton’s alibi was that he was somewhere other than Powell’s apartment when the shooting occurred. Detectives, however, learned that Cotton cancelled his cell phone and activated a different phone with a new number the day after the shooting. That key piece of information, combined with Cotton’s denial that he opened a new cell phone account, led investigators to believe that phone records could be the linchpin of the prosecution’s case. Rather than throw detectives off the scent, Cotton’s behavior focused their attention on all cell phone activity that day.

After the phone records of several suspects in the case were acquired from cell carriers, Brodey Hill, a GIS analyst for Kent County, used ArcGIS to digitally plot the suspects’ routes on the day of the crime using cell phone location data.

“We needed that information condensed so that we had time, phone number, and coordinates displayed in point symbology on the maps,” said Hill. “We color-coded the routes to distinguish them, which clearly placed the main suspect at the scene of the crime at the time that it occurred—no DNA required.”

Hill created two other key maps that displayed the route of the man who allegedly robbed Cotton derived from calls he made that day. The maps demonstrated that all suspects, except for Cotton, were in other parts of the city when the shooting took place. Maps created for the prosecution became the centerpiece of the trial.

Attorneys are accustomed to seeing a jury zone out when presented with numbers and tables. Exhibits of cell phone records, even enlarged, might display key facts of the case but lack the visual context to show how far away each phone call was made from the scene of the crime.

“Those maps were the glue that connected space and time in the jurors’ minds,” said Eslinger. “It was great to tell the jurors, look, this must be Powell’s murderer because the mapped phone records put Cotton at the scene and show the other suspects weren’t there. GIS helped us make that fact plain as day.”

Word Spreads

Since Cotton’s conviction, word has spread quickly throughout the county about the services and support Kent County GIS provides. Hill now regularly testifies as an expert witness in trials, explaining the significance of exhibits he creates with Esri ArcGIS.

“Consumer mapping doesn’t hold a candle to professional maps,” said Hill. “Displaying the county seal, legends, and labels—everything that defines an authoritative GIS map—amplifies the persuasive power of these exhibits, which is critical in murder trials lacking direct proof.”