February 11, 2019 |

January 21, 2020

By the time the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Force of Colombia (FARC) finally brokered a peace agreement in 2016, their 50-year-old civil war had claimed 260,000 lives.

Land reform was always at the heart of the conflict. As in many Latin American countries, most land in Colombia is concentrated among an elite group. Just 14 percent of all landowners control 80 percent of the land, a strong indicator of inequality.

During the war, some rural areas were effectively cut off from the rest of the country, as government troops, paramilitary groups, and the FARC fought over territory. So many people were driven from their land over the years that today Colombia’s displaced population—nearly 8 million—is the world’s largest.

Even for rural Colombians who have remained on their land, property rights are highly contingent in the post-conflict era. People who possess small plots of land have no official recognition of their ownership, or even the exact dimension of their plots.

“Without having a proper land administration system in place, the government doesn’t know about the relationships between the people and the land in these post-conflict areas,” said Chrit Lemmen, a professor of geoinformation science at the University of Twente, in the Netherlands. “That’s why it’s so important to make a full inventory and hand out titles whenever possible. These people have suffered for a long time—and now they’re waiting for the government to formalize their land.”

The contemporary state of land rights reveals much about post-conflict Colombia.

Regularization—a term referring to how land owners get their ownership rights legally recognized—is a pillar of the peace agreement. “A substantial part of the document involves implementing a new land administration system that grants land rights nationwide,” said Lemmen, who also advises Kadaster International, the international arm of the Netherlands’ official Land Registry and Mapping Agency. “It’s seen as a way to bring peace to the country.”

The Netherland’s Land In Peace project is a joint effort with the Colombian government to survey, map, and register small rural plots. The scale is massive. Cumaribo, just one of the municipalities covered by the project, is home to the indigenous Guahibo people. It alone covers an area 1.6 times the size of the Netherlands.

“A couple of years ago, the official estimate was four million parcels that need to be regularized,” said Mathilde Molendijk, Kadaster’s regional manager for Latin America. “The real number now is at least 12 million, and probably several millions more. Only five percent of the country’s land has an up-to-date cadaster, and nearly 30 percent has never even been part of a cadaster. So this is a huge task for the Colombian government.”

To regularize a parcel of land, surveyors must create a cadastral map that delineates the boundaries and borders. Cadastral surveying is usually a painstaking process. A complete survey of even a small piece of land in rough terrain can take up to a week. With 12 million parcels, finishing the job in under a century would require 2,000 full-time surveyors.

The economic cost is even more prohibitive. “In many African and Latin American countries, a conventional survey could be a year’s income for poor people,” Lemmen said. “The measurement of the parcel can be worth more than the parcel itself. If you follow the usual accuracy requirements, you have a system that’s only for the elite. I think it should be there for everyone.”

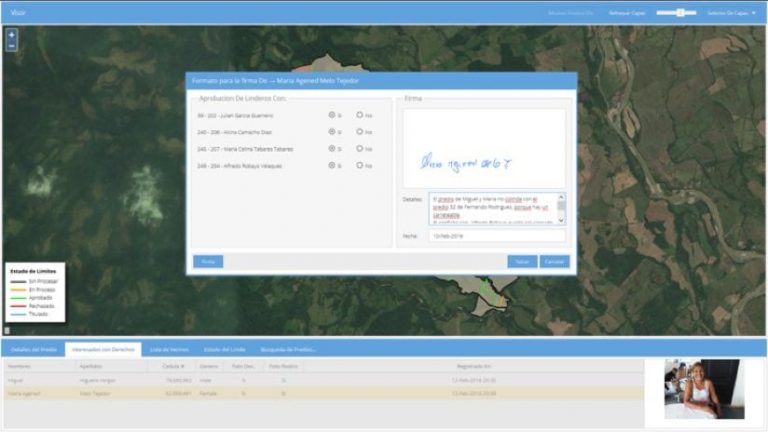

In lieu of traditional methods, the Colombian mapping program uses fit-for-purpose (FFP) surveying. A conventional cadaster strives for centimeter-level accuracy. FFP surveys operate on the principle that the perfect is the enemy of the good. Completing an FFP survey requires little more than access to a geographic information system (GIS) app running on a mobile device and when appropriate connecting to an external GPS device.

Conventional cadastral surveying establishes borders based on predetermined requirements such as the measurement of isolated points. FFP’s foundation is the “polygon,” GIS-speak for the shapes and blobs on maps we recognize as representing distinct real-world features, such as lakes, parks, or streets and parcels that are often delineated by physical boundaries such as hedgerows and fences.

For the Colombian Land in Peace project, the polygons are the parcels of land that already exist. Partly identifiable from satellite imagery, they become what the program’s proof-of-concept paper calls “evidence from the field.”

The FFP methodology does not require surveying expertise. Representatives from the Colombian government and the mapping program usually begin by identifying villages with unregistered parcels. Many villages have a Community Action Board (Junta de Acción Comunal), a legally recognized local governing body. “We work a lot with the village’s board, so they know we’re coming,” Molendijk explains. “We discuss the idea and whether they really want to measure their parcels. And they always do.”

After studying satellite imagery, the team and the villagers make a general plan for mapping the parcels in and around the village. Team members then organize short training sessions for the mobile GIS app. “The smartphone app is designed so everyone can use it, but younger people understand it very fast,” Molendijk said. “We explain to them how the connection works with the GPS antenna. And then, together with the farmers, they go to the parcel and measure the land. They also collect any accompanying documentation that connects the farmer to the land. And in about three days, we’ve measured the whole village.”

While the data-gatherers walk the perimeter of a parcel, the app gathers the data and draws the boundaries. As people from adjoining parcels do the same, the program begins to build boundary lines, initially displayed in black.

“It goes very fast,” Lemmen said. “As the people walk the polygons, you get observations from both sides of the boundaries. So each individual boundary is observed from two positions by two different people. And if those boundaries are within a certain tolerance, then you can assume agreement on the location.”

The app uploads the data to the cloud for storage and processing. At public meetings, the villagers examine the entire map. If neighbors on adjacent parcels agree on the measurements, the borders go from black to green.

“In the end, we hope all the lines are green, but if people don’t agree, the line displays as red,” Molendijk said. “Once we have all the information, the government should be able to process land titles.”

“It’s kind of a magic trick,” Lemmen added. “The wonderful thing is that they have a lot of confidence in the measurements because they do it themselves. And with the equipment, they can see every click on the screen and watch the parcel build up. At the end, they are very happy to see the polygon of their parcel.”

Even when the surveys yield dimensions at variance with a farmer’s informal deed of purchase, Molendijk has found the discrepancies rarely create new conflicts. “Since the farmers measure the parcels themselves, and can see it happening on their smart phones, they trust their data, even if the result is a parcel that is smaller,” she said.

Learn more about Esri solutions for land records.

February 11, 2019 |

July 5, 2018 |

February 1, 2019 |