ArcGIS Online is remaking GIS. We already take for granted how easy it is to make maps about anything and share them with anyone. And it’s not just maps. Data is becoming a social product, too. Partly through crowdsourcing (as Joseph Kerski recently wrote about here), and partly through projects like ArcGIS Open Data that help organizations offer their data like ice cream from a truck on a hot day.

But if GIS were a polygon, it would be a triangle: its vertices are maps, data, and analysis. Many people assume all analysis still has to be done in ArcGIS for Desktop. And it’s true that when it comes to geoprocessing tools, ArcGIS for Desktop is like Home Depot—it has everything you could possibly need (although you don’t always find it right away). By comparison, ArcGIS Online is like a good neighborhood hardware store. The inventory is smaller but it’s carefully chosen and more than meets your everyday needs.

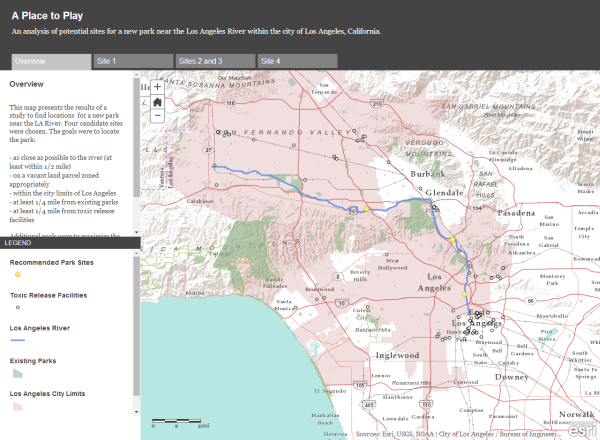

Recently, I did an ArcGIS Online analysis to locate a site for a new park near the Los Angeles River in Los Angeles, California. This wasn’t a full-fledged project for an Esri client, just a project put together for educational purposes—but it still had a fair amount of complexity.

If you’re not familiar with the Los Angeles River, you’re in good company with lots of people who live in Los Angeles. Once a natural river and the city’s sole source of water (until the completion of the Los Angeles Aqueduct in 1913), it was lobotomized and wrapped in concrete by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers after a major flood in 1938. It became a forgotten place.

Over the last 25 years, however, efforts to revitalize the river have slowly built enormous momentum. Last month, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers approved a $1 billion dollar proposal to restore habitat along an 11-mile stretch of the river where the river bottom is still mostly dirt.

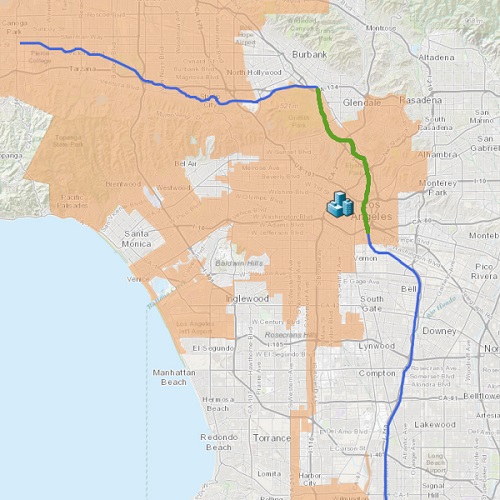

The LA River starts in Canoga Park in northwest Los Angeles and flows 51 miles to Long Beach Harbor. About 32 miles of its length are within the Los Angeles city limits. The stretch designated for major restoration is shown in green on the map below. The building icon represents downtown Los Angeles.

For this project, the siting criteria were that the new park should be:

- As close to the river as possible (at most 0.5 miles away)

- On vacant land suitably zoned for park development

- Within the Los Angeles city limits (but not necessarily within the $1 billion revitalization zone)

- Between 0.5 and 10 acres in size

- Not too close to existing parks (at least 0.25 miles away)

- Not too close to facilities that release toxic waste (at least 0.25 miles away)

Two additional goals were to maximize the number of people in the park’s “service zone” (defined as a 0.25 mile ring around the site) and to put the park in a less affluent neighborhood—measured by median household income within the service zone.

The starting data included parcels with vacancy and zoning codes from the City of Los Angeles. (This data was kindly shared by the City of Los Angeles, Bureau of Engineering, Mapping and Land Records Division.) Data for the city limits, the river, and parks came from Esri Data & Maps. Toxic release facilities were downloaded in Excel format from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxics Release Inventory Program website.

Data preparation was done in ArcGIS for Desktop. Preparation included clipping data to the area of interest, editing attributes, joining tables, geocoding facility addresses, and publishing hosted feature layers.

In ArcGIS Online, the first part of the project was to find the area that would be acceptable for a park.

1. I first drew a half-mile inclusion zone around the river. (Buffer tool)

2. I then drew quarter-mile exclusion zones around existing parks and toxic release facilities. (Buffer tool with the Dissolve option)

3. I merged the two exclusion zones into one (Merge tool).

4. I cut away the exclusion zone where it overlaid the inclusion zone (Erase tool).

The result was the park search zone, shown in blue in the image below.

The next step was to find suitable vacant parcels within the park search zone. In ArcGIS Online, attribute and spatial queries can be combined in a single operation that creates a new feature layer.

5. I needed to find vacant parcels meeting these conditions: (Find Existing Locations tool)

- Zoned to allow park development

- At least 0.5 acres in area

- At most 10 acres in area

- Intersects park search zone

- Completely within city limits

The result layer from the Find Existing Locations tool contained 76 parcels. I decided to narrow this initial set of candidates to a smaller number that were closest to the river. (The LA river is an inconspicuous locale. You can often be close by without seeing, hearing, or smelling it.)

6. From the 76 candidate parcels, I selected the 25 closest to the river. (Find Nearest tool)

The Find Nearest operation created a new feature layer of 25 parcels. These 25 advanced to the round of demographic analysis.

7. I drew quarter-mile park service zones around the 25 parcels. (Buffer tool).

8. I requested population and median household income attributes for the park service zones (Geoenrichment tool).

I then reviewed the table for the geoenriched service zones and identified six zones that had a population of 1,500 or more and a median household income of $60,000 or less. (The median household income for Los Angeles as a whole is about $50,000, so my cutoff value really wasn’t very low.)

Finally, I examined the parcels in these six service zones against an imagery basemap. I disqualified two of them because they were separated from the river by a major freeway. The remaining four were all viable, although each had some flaw that was revealed by visual analysis.

The final map is shared on ArcGIS Online with a story map application template.

In twenty years at Esri, I’ve seen periods of steady, incremental improvement in our software as well as times of breakthrough and change. We’re going through another paradigm shift now—to me, it seems more momentous and promising than anything in the past. ArcGIS Online will bring GIS to new audiences and give them access to huge troves of new information, but it will do even more. Its spatial analysis tools will introduce a new, diverse, and enthusiastic set of users to our special way of thinking about the world and our unique strategies for framing and solving geographic problems.