If you are new to the U.S. Vessel Traffic application from Living Atlas, then by all means, go check it!

Feel free to get the how/why lowdown from this introduction blog. Or just enjoy the slideshow below. Either way, welcome to some accidental lessons in Economic Geography…

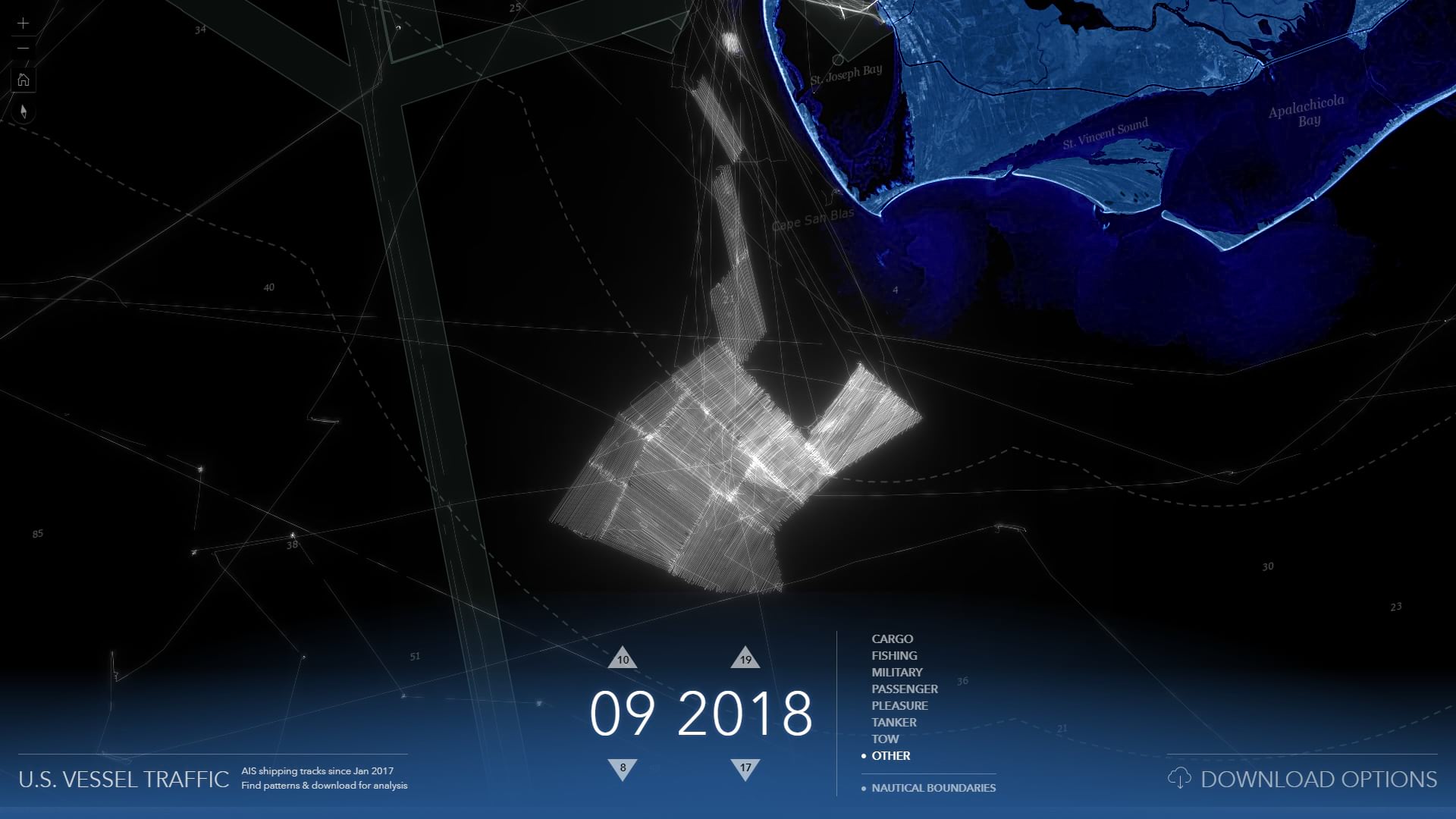

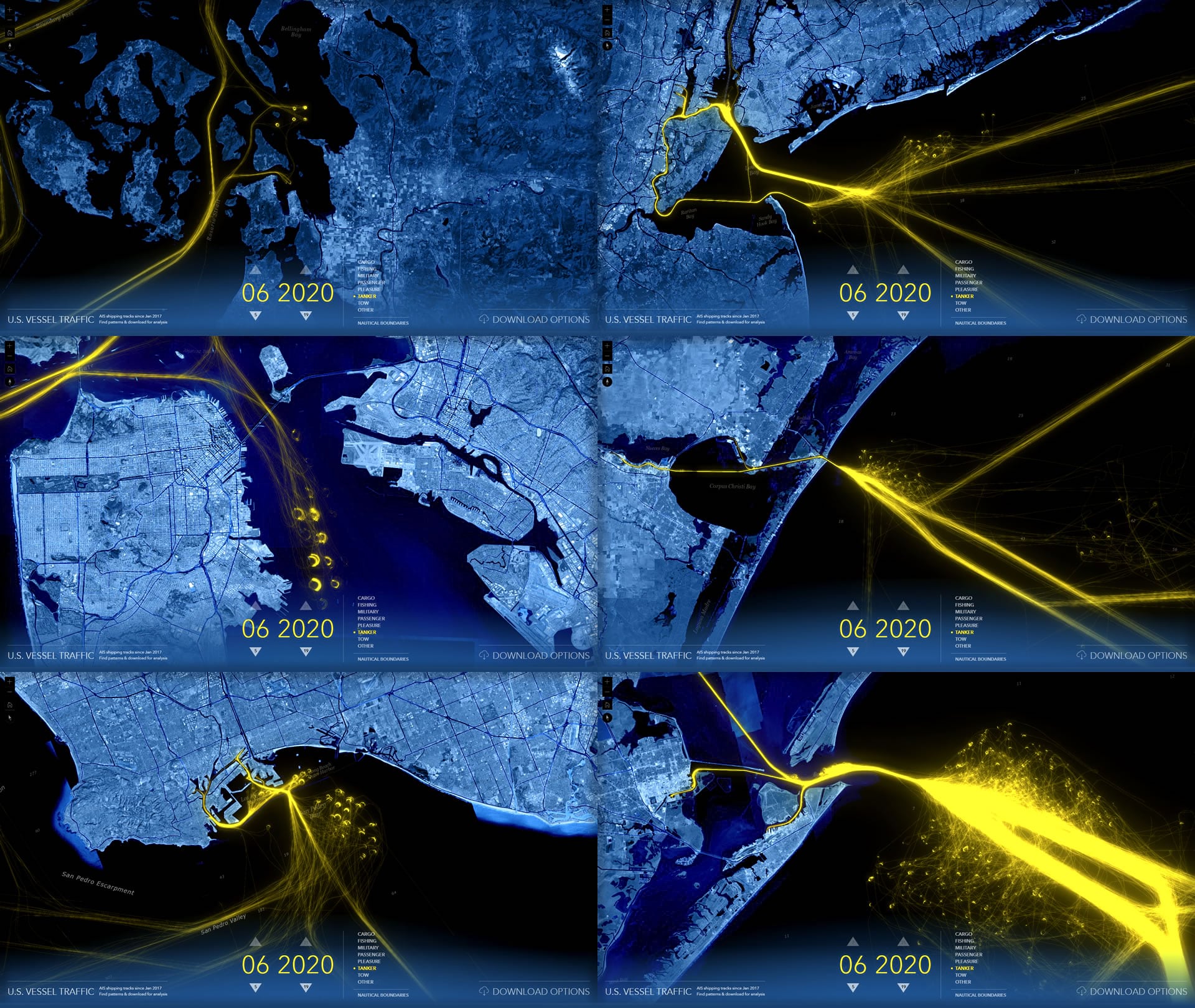

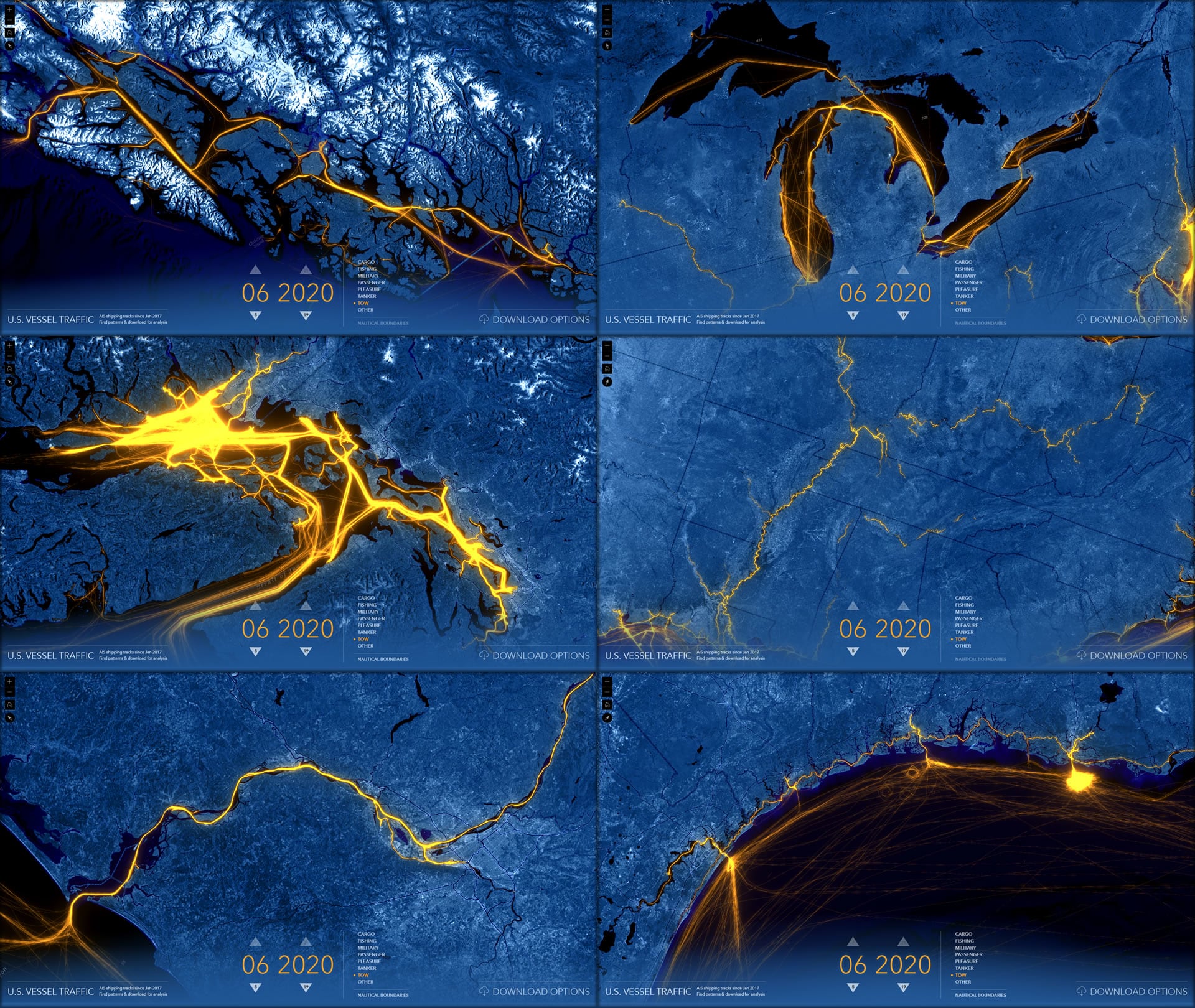

One of the primary tasks map readers are visually scanning for when we look at maps (or any data visualization, really) is a departure from randomness. This reveals structure at work and lets us start honing in on better and better questions. Clearly the overriding patterns of the vessels in and around U.S. waters is inherently structured. It’s a wide-open highway system with varying amounts of network rigidity.

But look at this blip of outstanding structure. Track lines like this can be the result of a survey vessel improving seafloor mapping or a research vessel conducting a biomass inventory to better manage fishing regulations.

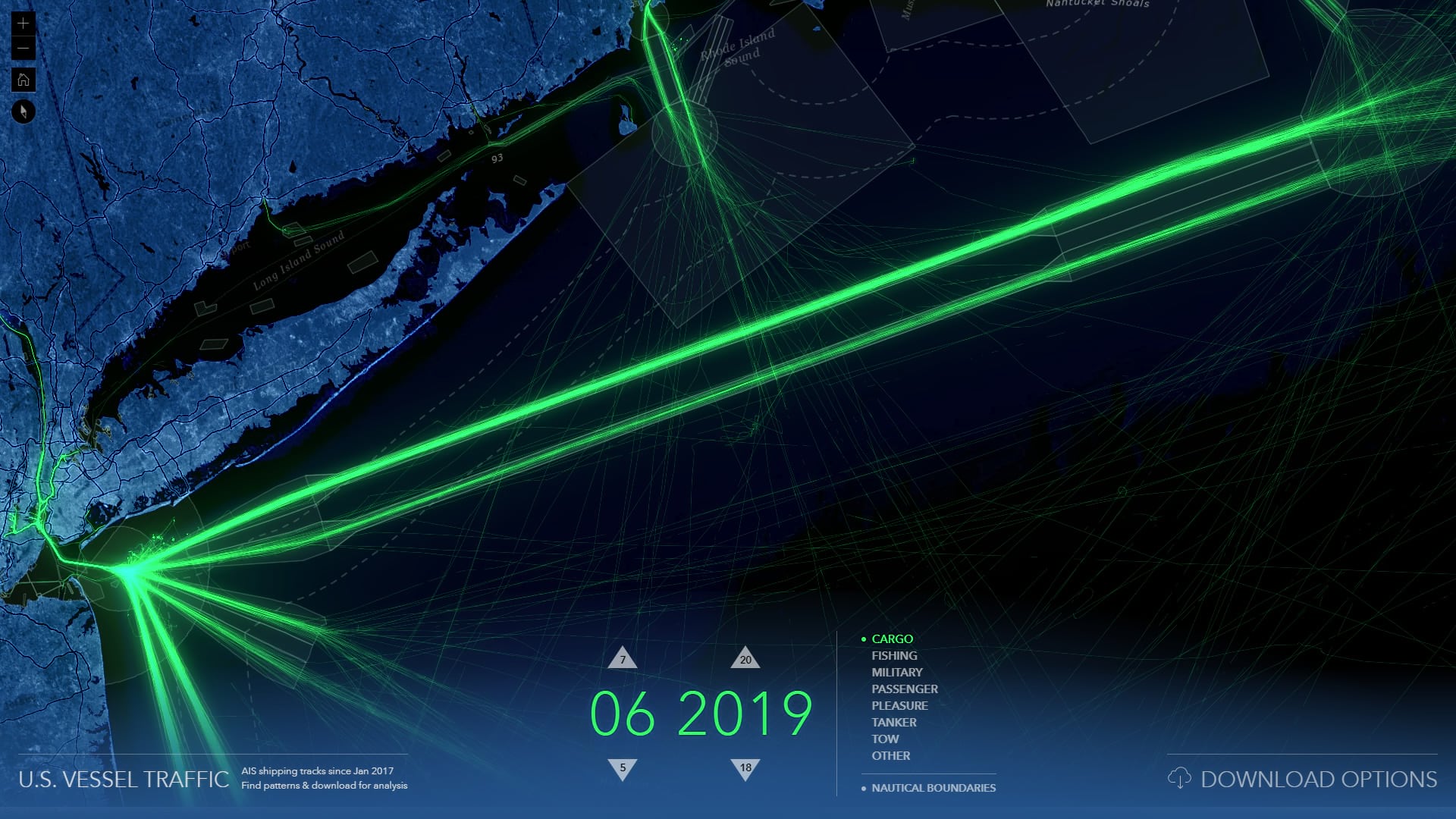

It’s easy to think of the open seas as requiring little to no traffic management. But massive cargo vessels change speed and direction very slowly and coastal areas can look much like a regimented highway system directing incoming and outgoing traffic flow with separation schemes and warning areas with speed controls and avoidance areas. When cargo traffic is seen in the context of maritime reference boundaries we see lots of boats following lots of rules.

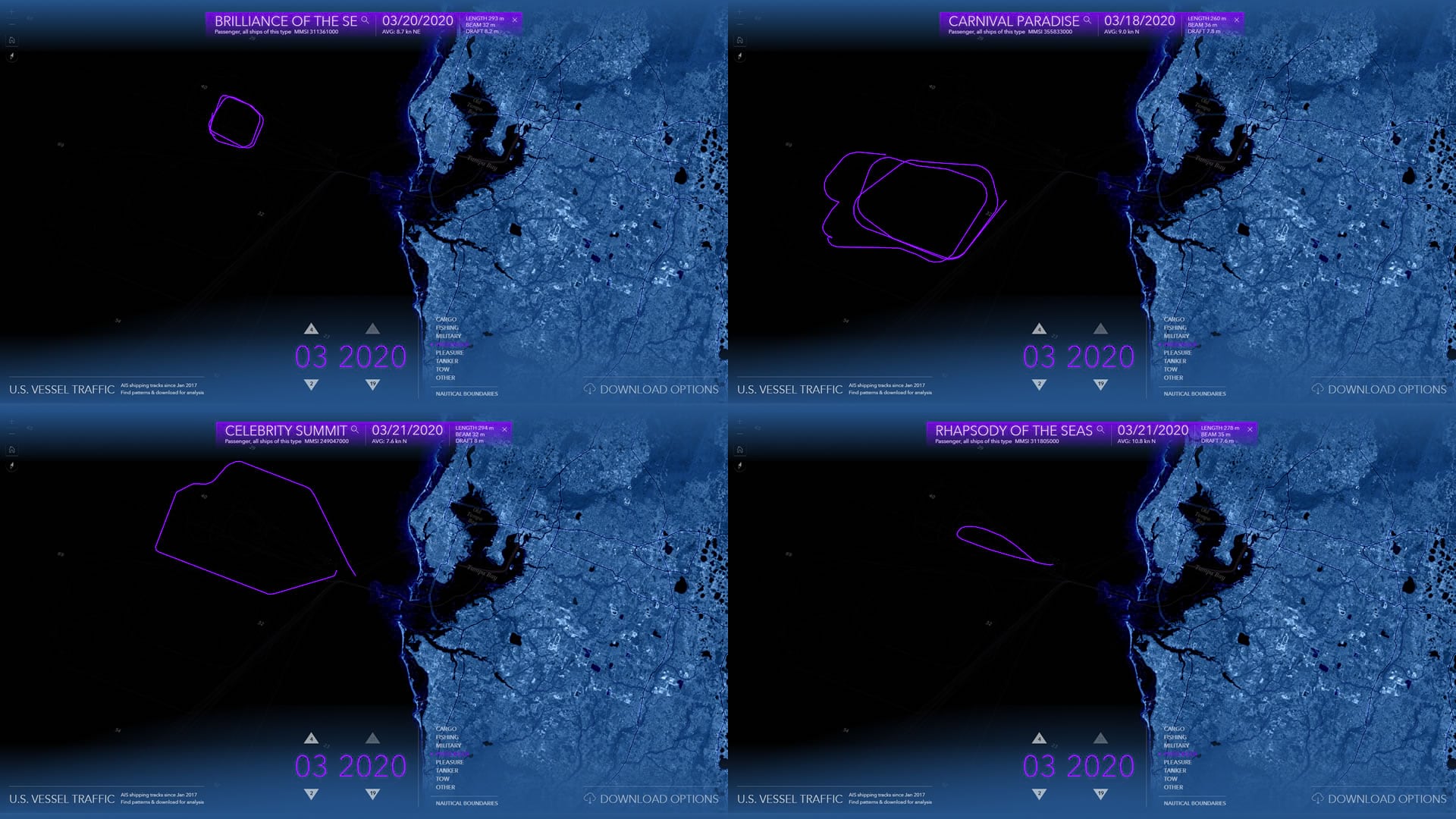

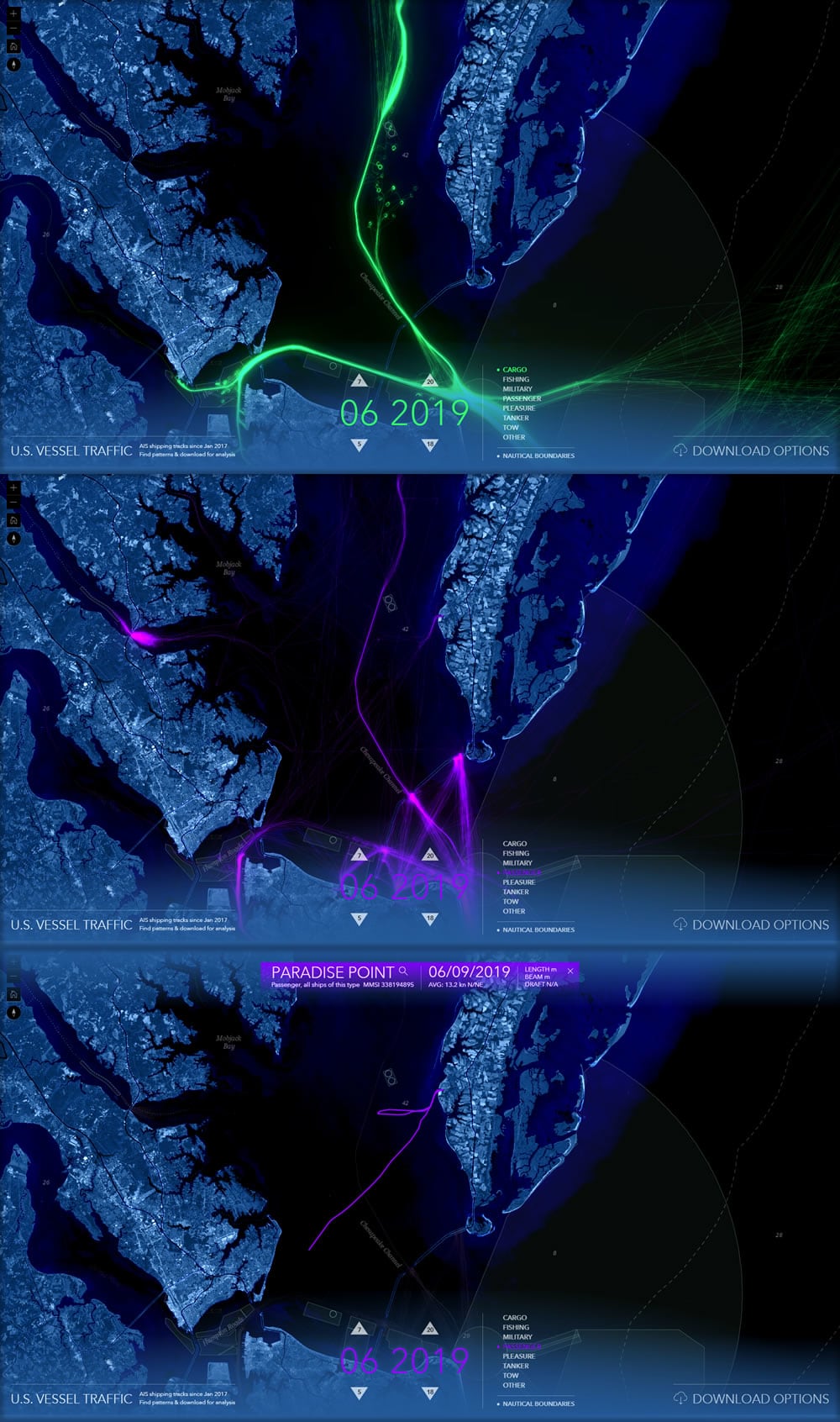

Speaking of rules, wherever there is a border there is opportunity. Here is an interesting pattern of passenger traffic taxing out to, then drifting at, a seemingly arbitrary location. But when we activate the boundary for U.S. territorial waters, this pattern makes sense.

So many of the vessel patterns that reveal themselves the manifestations of very human phenomena. Sometimes this is an entertaining revelation, like in the example above, but often it shows the sobering impact of something as seemingly unrelated as epidemiology. When locations in the United States were first responding to the spread of coronavirus in March of 2020, many cruise ships were caught in a limbo, unable to proceed into port with suspected cases aboard. These vessels, and their passengers, waited out the time churning in circles outside their port of call for days and weeks.

Similarly, areas without inland connectivity rely on vessel traffic to transport people and supplies about isolated communities. When travel restrictions were put in place, areas like the panhandle of Alaska, and in this specific case, the bustling waters around Juneau, were quieted.

Speaking of safely waiting, ports are busy places and there are a limited number of berths. Gigantic tanker vessels queue up and wait their turn to offload their supply; they idle in designated anchorage areas. The poc marks you might notice positioned adjacent to these hives of activity are the echo of tankers swinging at their anchor tethers with the incoming and outgoing tide like balloons in the wind. Patterns like this can help us ask questions about who and what might be affected by these scores of massive diesel engines idling just off the coast. Seeing these anchorages floating near dense urban areas or vulnerable marine habitats in the basemap imagery can provide context for pragmatic questions of environmental stewardship, or inform considerations of air quality and public health.

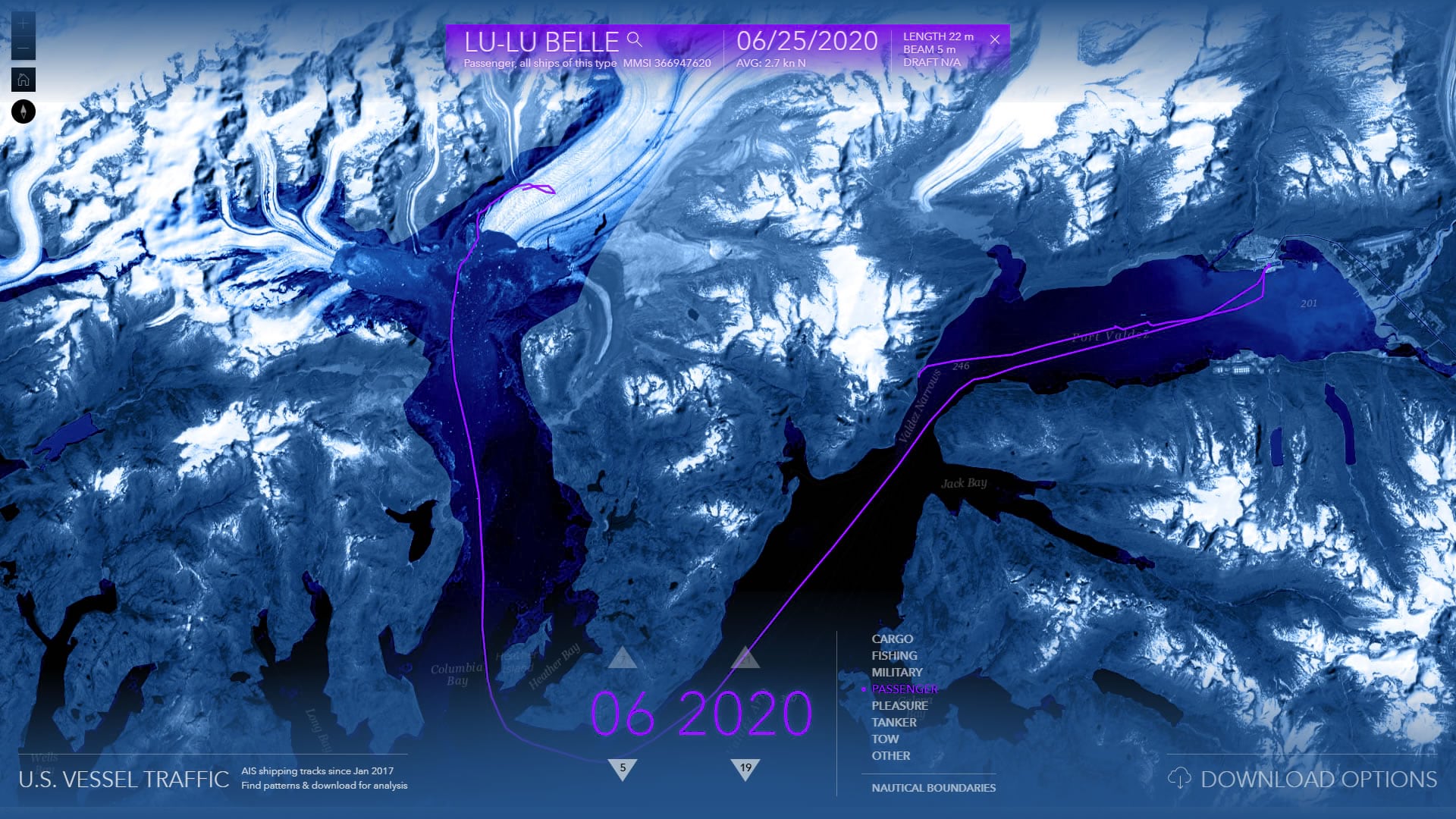

Idling nearby is a sensation anyone who has been on a glacier boat tour can appreciate. In this example of glacier tours departing from nearby Valdez, Alaska, the vessel path data effectively traces the edge of the calving Portage Glacier, outpacing the underlying imagery. By clicking through the years, these paths can be seen moving deeper and deeper into what was formerly an icefield.

Speaking of ice, the Straits of Mackinac are no stranger to lots of shipping traffic, connecting Chicago to the eastern United States—but sometimes all the straits ship is ice. Compare these images of tow/tug traffic between Summer and Winter. Tow vessels strive through the winter to maintain a navigable channel, and cargo flows through surprisingly deeply into January, but most years see a freeze-up in February that even ice breakers can’t keep up with. Ultimately, nature decides who comes and goes, and when.

Tow/tug boats are the workhorses of the waterways. They break ice, ferry barges, artfully shepherd massive tankers through cramped ports, and in general go where other vessels just can’t. Do you recognize any of these areas?

Frequently tow vessels take over for other larger ships when waterways prohibit the behemoths of cargo and crude. As large as the Mississippi river is, at some point its depth and crossings make it impossible for the large vessels to proceed. Notice where tanker and cargo ships meet their clearance limits; tow vessels take their shipments and ferry them deeply inland.

This sort of inter-vessel coordination allows a remarkable connection of goods…and people. In particularly precarious waterways, specialized local pilots are ferried out to large awaiting vessels who benefit from their focused knowledge, assuring safe navigation. The handoff can be a precise dance that includes jumping to ladders of still-moving vessels.

Often the patterns that emerge are echoes of much deeper natural cycles and undersea structures. Have you ever watched a flock of birds artfully swoop and dive almost like it is a single entity? Each bird is an independent creature, moving of its own volition under its own power, but when seen in sufficient numbers these individual agents reveal an underlying cooperation and a singular intelligence. Look at the seasonal swarming of fishing vessels along the undersea precipice of the Cascadia Basin. These fleets are fishing at the seasonal migration patterns of salmon, roaring into action in the spring and the fall. Additionally, if nothing of the bathymetry in this area was known, you might be able to trace out a fairly precise path of the oceanic shelf.

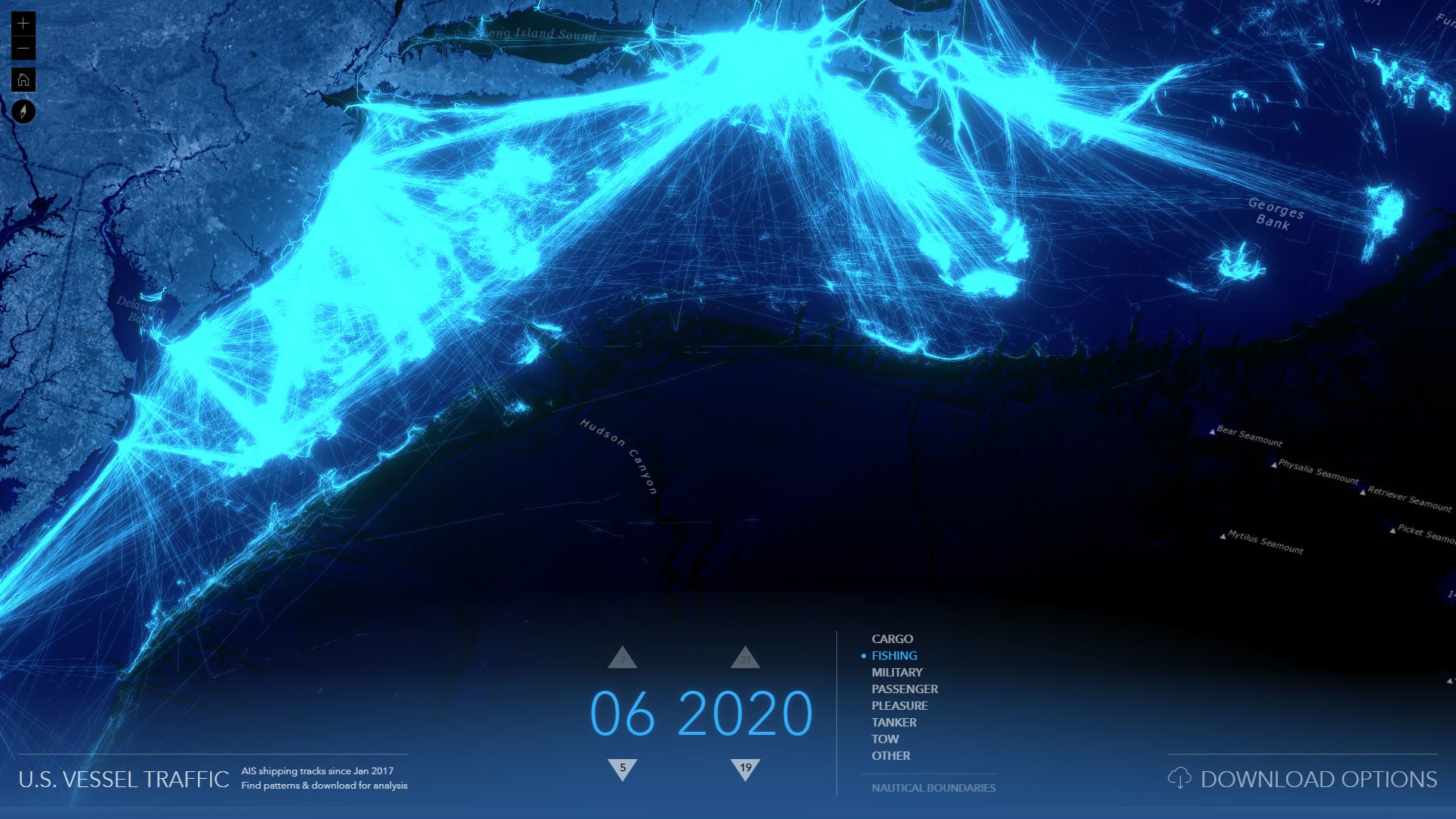

Similarly, note the exquisite precision with which hundreds of fishing vessels trace the bathymetric rise along the Eastern Seaboard, a glowing reflection of undersea structures and a warm Gulf Stream giving rise to a localized food chain.

We hope you’ve enjoyed this tour of interesting examples of the patterns that big data reveal. Enjoy the U.S. Vessel Traffic app and discover the patterns that give rise to your own questions. Enjoy!

Article Discussion: