USER STORY

Rural Water District Gains High Accuracy on a Budget

By: Travis Anderson - District Engineer, Le-Ax Water District

The work Travis has done with Collector is tremendous. It has allowed Le-Ax to easily and economically deploy GPS technology to our field crews. The Esri Collector app, loaded onto our iPads, made operations in the field very straightforward. Nowadays, even if a worker considers himself computer illiterate, I'll bet they own a smartphone. The Esri Collector app turns those employees who can operate a smartphone into a GIS field technician in the simplest of terms. I am excited about the possibilities this will bring Le-Ax, but also other water and waste water operators across the country. I am proud that Travis has been a part of this with Esri and his participation helped in deploying Esri's Collector app. - John Simpson - Le-Ax Water, General Manager - Ohio Rural Water Association Board Member, Chairman Membership Committee

When I came to work at Le-Ax Water District staff had just finished gathering GPS points on all the aboveground assets. With Ohio University's Institute of Local Government Administration and Rural Development (ILGARD) providing technical resources, Le-Ax had finally put together all the pieces and had a functioning GIS. From that point on, it was the district's responsibility to maintain it.

The continued task of gathering GPS points was assigned to the maintenance crew. Since they were responsible for installing taps, meters, and valves and making repairs and exposing lines, it made the most sense to have the crew collect the asset locations. Periodically, I would take the handheld GPS unit from the staff and put the new points into ArcMap. The workflow seemed pretty straightforward, but it became apparent fairly quickly that this transition to the district's maintaining the GIS would not be an easy one.

The two main problems that came to light were the staff's limited technical knowledge of the equipment/software, and the amount of time the handheld unit needed to acquire accuracy. The first problem was corrected by creating cheat sheets for the staff. If the cheat sheet couldn't answer questions or refresh the memory, a phone call generally would solve the problem. The second problem became a much more contentious issue. As the crew would be ready to backfill a repair, the person responsible for gathering the points would be waiting on the handheld GPS unit to achieve accuracy. Sometimes it would take 20 seconds; sometimes it was minutes. This became really frustrating for everyone.

Le-Ax plodded along with the handhelds, but it was not a productive period for our GIS. We had lost buy-in from staff. This was about the same time when apps were exploding in popularity and everyone was getting a smartphone. Searching the marketplace, I came across a simple mobile app that utilized shapefiles by projecting them onto an aerial-imagery background. The internal GPS of the phone would show the location. It wasn't accurate, and it wasn't easy getting the coordinates set up, but it did work. When I showed the app to staff, everyone's attitude toward GIS changed. That was the aha moment for Le-Ax. We put a useful tool at everyone's fingertips, everyone used it, and it didn't cost a dime.

Le-Ax was definitely at a transition point for gathering field data. When Collector for ArcGIS was released, I knew this would be our next step toward using iPads in the field—I just had to figure out how to use the app. Before coming to Le-ax, I knew little about GIS. Everything I have learned has been self-taught. A lot of my knowledge has come from Esri's online communities. A search on Esri's website revealed plenty of dialog between users and Esri support staff that answered many of the questions I had. Online tutorials for Collector provided guidance on creating maps and making them accessible in the Collector app. It was all very simple to figure out. The remaining piece of the puzzle to fully implement Collector was a subscription to ArcGIS Online. Since we already had an ArcGIS for Desktop Basic seat and the yearly maintenance subscription, Esri provided us with one free ArcGIS Online account. After reading the basics on creating online maps and sharing them within our organization, I began uploading our layers and re-creating our desktop GIS in ArcGIS Online. After I understood the concept, it took me about 30 minutes to re-create our desktop GIS as an online version.

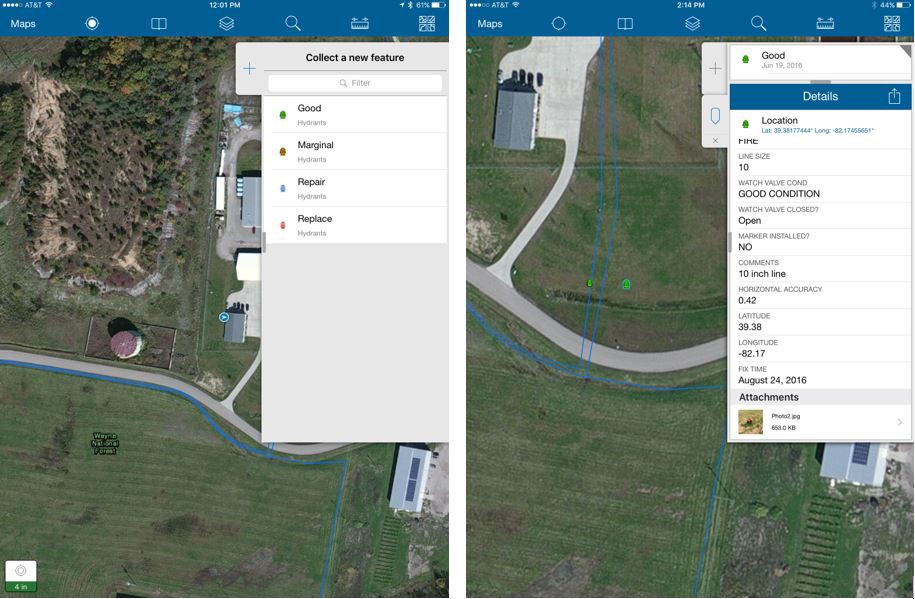

Once I created the map, we were able to test the functionality of Collector with our iPad. As a field-specific app, Collector is similar to ArcPad but easier to use. It is very intuitive. A blue circle shows the GPS receiver location, and across the top is a very functional toolbar. To access the layers, you tap the layer symbol and a drop-down list will show the layers contained within the map. You can take a picture by tapping the camera icon on the top toolbar, then point and click. After you're done, click the Submit button. Everything will be updated and stored safely in ArcGIS Online. I can't stress enough how easy Collector is to use.

As well-thought-out as Collector is, I still had two major concerns: connectivity and accuracy. Athens County, in southeastern Ohio, is not what you would call a booming metropolis of cellular activity. Sure, along the major highways you may have a data connection, but we are a rural water district. We serve almost 7,000 taps spread out over 500 miles of waterline in four counties. We have waterlines in places where you can't imagine someone having the nerve to drive a track hoe. We have many miles of waterline that are nowhere near a data connection. If Collector was going to work for us, we had to be able to do our work with no connectivity—offline. Having searched the online communities, I knew Esri was working on this feature, but I didn't know how it was going to function. I was worried that the process of going offline would be too specialized for our staff to utilize. It couldn't be something where I was relied on to set up every time someone was going to an area with no data service. With the release of the Collector update that provided the ability to work offline, Esri couldn't have created it any better. It was basically a two-step process. I showed our staff one time how to use this feature, and no one has had to ask for help since.

My final concern was accuracy. We loved everything about using the iPad with Collector. We had a field-ready tool and app with capabilities that far outweighed the handhelds we had used in previous years. Our staff now could get their email, check weather conditions and receive weather alerts, send pictures back to the office from the field, and opt to use other apps. Also, when a data connection is available, there is nothing like real-time data collection. The user clicks the Submit button, and suddenly there's a valve on the map that I'm looking at back in my office. That's pretty spectacular. But even with all these advantages, if we couldn't get to a level of accuracy that would allow us to locate that valve or that waterline one month or five years later, then all this would be for nothing—because that's what this is all about: locating an asset and then being able to get back to that asset based on the GPS data. From the beginning, we knew that we would need an external GPS receiver and it wasn't going to be an inexpensive purchase. After due diligence on specifications, we chose the submeter performance of the Arrow 100. Before we purchased it, we actually rented the receiver for a couple of days to test it with Collector and the iPad. Three features that sold us on the Arrow 100 were that it was certified by Apple to work with the iPad; it had class 1 Bluetooth transmission (a greater connection range); and beyond the correction service that the receiver provides, it could connect to the Ohio Department of Transportation (ODOT) real-time kinematic (RTK) network and achieve very high accuracy. Coupled with the speed that the receiver would connect to satellites (<60 seconds) and its very quick response to taking points, I felt like we finally had the last piece to our puzzle. The days of waiting 30 seconds to get a point were over. Points now come as fast as you can click the buttons.

Esri's release of Collector 10.4, which included support for high-accuracy external receivers, put the finishing touches on an already great app. Metadata could now be captured and passed to the attribute table. Being able to see and keep a record of each feature's data accuracy builds confidence in your process and staff. It also allows you to verify the performance of the equipment. If accuracy levels seem off and you look closely at the points on the map, maybe you'll notice the large stand of pine trees that was interfering with the signal—or if, instead, the points are in a wide-open field, you'll know that it's time to check the equipment.

The other feature that proved valuable was the correction profile setting that allows datum transformations. Many counties and states have their data on the state plane coordinate system. Here in Ohio, our department of transportation has its correction service set up on NAD83. In order for me to use that correctly, I need to transform the datum to make sure everything matches. Once you have this set up, the corrections are made on the fly. This allows you to achieve very high-accuracy data collection.

As a final thought, I would be remiss if I didn't mention something about the budget. Everyone has a budget that they would like to stick to. And it's very easy to spend an exorbitant amount of money on items related to GIS and GPS. I did not want to spend a large sum of money on an external receiver just to have it sit on a shelf, like the other two handheld units. So we were cautious and moved slowly. I believe that in the end, we put together a really nice field solution on a pretty decent budget. We could have spent three times as much on a receiver that was supposed to have subfoot performance, but I felt that by collecting 8 cm accuracy online and half-meter accuracy (at the worst) offline, we were in good shape. The assets we look for include a valve box, which is around 9 inches across; a meter pit lid that is 16 inches across; or a waterline trench that's at least 2 feet wide. If we can't find any of those, then there's something wrong with the human locator.

In the end, we invested around $3,700 dollars. We did have the yearly maintenance subscription for our seat of ArcGIS for Desktop Basic, which afforded us one free account to ArcGIS Online. We used that account to initially test and set up our online maps. We have since acquired a five-seat license for ArcGIS Online, so we can deploy multiple iPads in the field and allow office staff to take advantage of our online maps. The beauty of ArcGIS Online is that all your maps are accessible to anyone within the organization.

We have been thrilled with our entire transition to this new field solution. With its external GNSS support, Collector has made it so easy for us to make this move. If there are other water utilities contemplating going in a direction similar to ours, I would encourage them to do it. Being a member of the Ohio Rural Water Association, I know there are many small water utilities and villages out there that have no idea where to begin with GIS. It can be overwhelming and expensive. But take it from someone who doesn't have a GIS background—this can definitely be done, even on a budget. You don't have to jump in, feet first, and purchase an external GNSS receiver. Simply start with a $400 or $500 tablet, download Collector, and see what you can do with it. You don't have to spend thousands of dollars on consultants. And you don't have to worry about storing and backing up your data. Everything is in place. All the tools are there for you to use. You just need to take the first step.

By: Travis Anderson - District Engineer, Le-Ax Water District