|

|

Please Note

Due to a printing error, the numbers identifying the three maps of the proposed Langoue National Park were left off of page 12 in the printed version. Please see above for the correct numbering order. Also, the photo credit for the two photos published on the same page did not print. We want to be certain that Michael Nichols of the National Geographic Society is credited with the photos (see below). Esri sincerely regrets any confusion, inconvenience, or misunderstanding these inadvertent printing errors may have caused. |

We have a plan: to create the Langoue National Park. It will comprise as much of this Yellowstone-sized area that we can negotiate back into the public domain; we are hoping for approximately 600,000 acres (see map 3). This will protect the clearing, the core area of the wilderness, and all key sites--all circumscribed by natural boundaries. The problem is this is going to take money, about 3.6 million dollars. When I see weekend boats parked in the Potomac worth twice as much, I think surely we can come up with this money, but it is hard. What we at the Wildlife Conservation Society are asking you to do is to donate to the Langoue Fund. This is not a normal appeal, this is urgent and for a very specific, tangible, and exceptionally important thing. If we can come up with these funds in the next few months it is likely that we will be able to negotiate for the logging rights to this land to put it back in the public domain. The government of Gabon has given us the green light to do this and in the next few months we will be vigorously pursuing this effort. Getting the land back into the public domain clears the way for the creation of the national park.

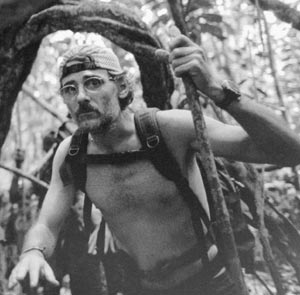

At right: Michael Fay documented in minute detail the elephants of the region. Below: Gorillas gather in Mbeli Bai, a natural forest clearing. Photos by Michael Nichols, National Geographic Society. At right: Michael Fay documented in minute detail the elephants of the region. Below: Gorillas gather in Mbeli Bai, a natural forest clearing. Photos by Michael Nichols, National Geographic Society.

Think about this. There are 300,000 copies of ArcNews that go out quarterly. If every recipient contributed $10, we would have nearly what it would take to go right to the loggers and the government with sufficient funds to get the job done. This opportunity to save the world's most remote gorillas and forest elephants is now. (To see these gorillas and elephants, visit www.savethecongo.org.) Ask your friends and family; give them a couple of acres for Christmas.

Most people think that national parks are created by committee in some deep bureaucratic office in one of the world's capital cities; not true. They are mostly created by individuals and grassroots movements. I work with the Wildlife Conservation Society in New York, and we are in the Business of creating the Yellowstones of the central African forest. We have been successful in several similar ventures in the past 10 years including Dzanga-Sangha National Park and Nouabale-Ndoki National Park comprising more than 1,500,000 acres. Just in the past month a partnership between a  logging company, WCS, and the Congolese government has cleared the way to add 60,000 acres of pristine forest to the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park. This place is called the Goualougo, and it has the last population of truly untouched chimpanzees that we have found. These are real, bona fide parks with substantial infrastructure, personnel, and a history in these countries now. They have become, in a short time, very much a part of the landscape here. They survive wars and economic downturns and have become part of the national heritage. logging company, WCS, and the Congolese government has cleared the way to add 60,000 acres of pristine forest to the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park. This place is called the Goualougo, and it has the last population of truly untouched chimpanzees that we have found. These are real, bona fide parks with substantial infrastructure, personnel, and a history in these countries now. They have become, in a short time, very much a part of the landscape here. They survive wars and economic downturns and have become part of the national heritage.

In Gabon we are lucky to have Lee White who has lived in the country for the past 10 years and is well known and respected. He has shown the Minister of Forests and Finance this place we call Langoue, and they have shown interest. Loggers are willing to negotiate and even accommodate this project. If this effort is to succeed it will be because we have Lee and his partners working on the ground.

Yes, there are big risks. There are several entities that we need to deal with, all differently. The government may see logging as more beneficial. Political change may come that is not as open to the idea. Pushing national park legislation can get bogged down. The biggest risk, however, is that we fail in accruing the necessary funds to spend what it takes to get logging rights back in government hands. In general, we are talking about $6.00 an acre. This is a good time to do this because wood prices are currently down, and logging companies are strapped for cash.

In the meantime we have built a camp and put a team of people from the government and WCS on the ground to hold the forest as it were and to mark a presence. We are starting to create a sense of place for the Langoue and will put all of its riches on Gabonese national television building internal support for this effort. Logging companies will be able to see what this place is about. We have already obtained funding for this effort permitting us to maintain teams indefinitely. Now we desperately need to build this fund for the logging rights. This is a good opportunity to make a real contribution to sensible conservation. It would be crazy to let this place disappear from the planet because we couldn't come up with 3.6 million dollars. If we get more, we will buy more.

For more information: www.savethecongo.org.

[Don't miss Michael Fay's March 2002 progress report.]

To learn more about the Megatransect, see the sidebar and the full-color map mailed with the hard-copy issue.

Thanks for making the Langoue National Park.

ArcNews home page

|

|

never seen humans, and giant elephants with two 100-pound tusks. There is a clearing of about 100 acres created by elephants in the heart of this forest where large mammals congregate to drink and socialize, like a wildlife metropolis, with a sophisticated trail infrastructure that radiates from it for tens of miles around. This is an ecosystem that functions as if our species didn't exist on the planet, not a single human infrastructure in more than 1,000,000 acres.

never seen humans, and giant elephants with two 100-pound tusks. There is a clearing of about 100 acres created by elephants in the heart of this forest where large mammals congregate to drink and socialize, like a wildlife metropolis, with a sophisticated trail infrastructure that radiates from it for tens of miles around. This is an ecosystem that functions as if our species didn't exist on the planet, not a single human infrastructure in more than 1,000,000 acres.

At right: Michael Fay documented in minute detail the elephants of the region. Below: Gorillas gather in Mbeli Bai, a natural forest clearing. Photos by Michael Nichols, National Geographic Society.

At right: Michael Fay documented in minute detail the elephants of the region. Below: Gorillas gather in Mbeli Bai, a natural forest clearing. Photos by Michael Nichols, National Geographic Society. logging company, WCS, and the Congolese government has cleared the way to add 60,000 acres of pristine forest to the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park. This place is called the Goualougo, and it has the last population of truly untouched chimpanzees that we have found. These are real, bona fide parks with substantial infrastructure, personnel, and a history in these countries now. They have become, in a short time, very much a part of the landscape here. They survive wars and economic downturns and have become part of the national heritage.

logging company, WCS, and the Congolese government has cleared the way to add 60,000 acres of pristine forest to the Nouabale-Ndoki National Park. This place is called the Goualougo, and it has the last population of truly untouched chimpanzees that we have found. These are real, bona fide parks with substantial infrastructure, personnel, and a history in these countries now. They have become, in a short time, very much a part of the landscape here. They survive wars and economic downturns and have become part of the national heritage.