ArcUser Online

Another major portion of this project involved scheduling and managing data collection sessions with water system personnel. With 14 systems included in the project, WARC staff members were hesitant to schedule data collection in too many systems at once. Because water department employees' schedules tended to be fluid (no pun intended), it was often difficult to coordinate fieldwork days. WARC dedicated one employee to this project at all times and, when needed, additional assistance was divided among three other full-time employees and part-time college interns who were available. Limiting the number of systems analyzed to two made organizing incoming data and managing schedule conflicts between data collectors and water personnel easier. Collecting DataData dictionaries were created and loaded into the Trimble GPS units. These dictionaries contained listings of the features that field-workers would encounter while collecting data on the water systems. It was important to the integrity of the final map products that meters, control valves, system valves, water mains, fire hydrants, pumping stations, tanks, wells, generators, springs, and treatment plants be located. Menus for individual listings allowed WARC employees to collect additional information such as the size of a feature, the county and system in which the feature was found, the type of feature (e.g., gate versus butterfly valve or fire versus flush hydrants), and other information that became more important than the WARC staff originally anticipated when completing the project's final maps. While in use, GPS units had to remain stationary over each individual feature for a minimum of 20 seconds to record its position accurately and completely. The data, saved by the GPS units as waypoints, was transferred to the computer using Pathfinder software. Collecting lines required an antenna mounted on the roof of a vehicle and connected to the GPS unit. Water department employees instructed WARC staff where the lines were located; staff members then drove along the lines as closely as possible. For particularly difficult areas, lines had to be added or connected back in the office. Weather conditions, cloud cover, satellite position, landscape features, and human-made features affected the accuracy and ease of data collection. Surprisingly, depending on the position of the satellites, it was often more difficult to obtain a steady signal on a clear, cloudless day than on an overcast or rainy one. Features located near power lines, under trees, or next to buildings were almost always more difficult to collect. Ultimately, more than 1,000 individual features were collected in Bibb and Hale counties and more than 7,000 features collected in Pickens County (despite the fact Pickens County system officials opted not to have meters mapped due to time constraints). Editing the Data

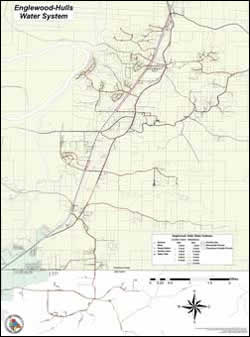

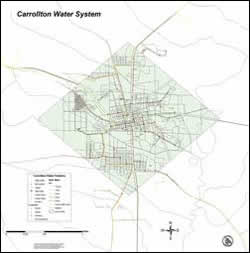

Once the data was successfully collected and returned to WARC offices, it was downloaded, corrected, and exported as shapefiles and accessed using ArcGIS. For some water departments, AutoCAD files of the lines were obtained from the engineering firms originally hired by the water departments. Generally, this data did not overlay well with the collected data and had to be edited extensively. As a result of the conversion processes between the software programs, lines were often misplaced by several miles. Much of this data was outdated and inaccurate. In addition, features such as valves and hydrants originally created in AutoCAD did not convert as single graphics but as collections of individual lines shpaed as the intended object. These features converted into large symbols that were less accurately located than features acquired using GPS. Originally, U.S. Census TIGER files were used for the roads in all three counties. These files were also not very accurate when placed on top of orthographic photos of the areas. Roads were located several miles from the correct position and often were not correctly shaped. TIGER files for each county were edited so when waterline files were added to the project, they could be more accurately placed relative to the roads. The road lines did not always intersect cleanly and required additional data editing. It was extremely important to have accurate road networks because the waterlines can cross roads multiple times. Editing road networks became essential for producing accurate maps that showed waterlines on the proper side of the road. Because lines needed to connect through the control valves, they were sometimes shifted slightly. ConclusionThe maps produced by the project will save time, energy, and money by assisting responders from water departments to locate lines and features more quickly and efficiently. Darren Rice, superintendent for the Englewood-Hulls water system in Hale County, said, "We are very excited to get these maps. It's going to help our employees readily locate features, and to be able to see everything in this system right there on the map will be great. We could have used this a lot in the past. I know it is going to be very helpful to us." With a detailed representation of every feature in the system, water department employees will be able to locate and repair damages more quickly. They can also assist employees from other utilities, such as natural gas companies or sewer departments, locate water lines and prevent accidental breakages. WARC presented paper copies of the maps to the individual water departments and provided each with the shapefiles associated with their specific water system. The data was also given to a variety of agencies including the Appalachian Regional Commission, Alabama Department of Environmental Management, and Alabama Rural Water Association. Future projects, similar to this one, are currently being planned by WARC. Water departments in surrounding areas served by the commission have expressed interest in also having their systems mapped. In addition, some towns included in the initial project are considering having their sewer and gas systems mapped using ArcGIS/GPS technology. There are plans for integrating GPS and ArcGIS capabilities into hazard mitigation plans that will be revised for all seven WARC counties as well as a project aimed at mapping and restoring an historic tramway path on the grounds of Tannehill Ironworks Historical State Park in Tuscaloosa, Bibb, and Jefferson counties in the central-west portion of Alabama. For more information, please contact Melissa Mayo, Planner About the AuthorMelissa Mayo works as a planner for the West Alabama Regional Commission in Northport, Alabama. She began in WARC's intern program working on the ARC GIS/GPS project before she was hired full time. Prior to working on this project, her primary GIS experience came through college coursework and projects for which she analyzed diffusion patterns of a medieval reenactment organization and determined optimal locations for events. She received a master's degree in geography from the University of Alabama and a bachelor's degree, also in geography, from Jacksonville State University in Alabama. |