Mystery dating from 1922 solved

When he happened upon Scott Doody in the Herrin City Cemetery in Illinois in March 2010, geospatial scientist Steven Di Naso could not have known that this chance event would lead to one of the greatest challenges of his life.

Doody, a historian, had been looking for the better part of a year for the grave site of a decorated World War I veteran who was killed in the infamous but now largely forgotten Herrin Massacre of 1922. He was searching for a single marker erected by the Veterans of Foreign Wars post in Chicago to honor Anton Malkovich, but it had vanished.

The search for Malkovich’s grave site eventually became a four-year-long, interdisciplinary project that would locate the unmarked graves of the other men killed in the Herrin Massacre. It was the first attempt to find these grave sites using GIS. (For information on the Herrin Massacre, see the accompanying article, “Casualties in a Labor War.”)

Although the story of the Herrin Massacre was well documented, the event was so atrocious that it was not spoken of for generations. In time, the locations of the unmarked graves of the men killed were forgotten.

Twenty-three men were killed in the massacre. Seven bodies were immediately claimed by relatives. The bodies of the remaining 16 men were buried in the potter’s field, an area of the cemetery reserved for the indigent, the unknown, and the unidentified.

Within four months, five of the bodies in the potter’s field were disinterred and claimed by relatives. On October 3, 1922, Ignatz Kubinetz, who had been injured in the massacre, died of his wounds and was buried in the potter’s field. This brought the total of unmarked grave sites from the Herrin Massacre to 12.

A Missing Potter’s Field

Nearly a century later, a team of geospatial scientists, historians, and forensic anthropologists came together in an attempt to locate these lost burial sites. Could the long-forgotten graves of the victims of the Herrin Massacre be found by applying GIS techniques?

Di Naso, a geospatial scientist, was confident the mystery would be solved with geographic information science. The cemetery’s long-held secret would be revealed not by mapping what was on the surface, but what lay beneath the surface.

Members joined the multidisciplinary, integrative research team as additional expertise was required. The team eventually consisted of principal investigator Doody; Di Naso; geographers Dr. Vincent Gutowski and Grant Woods; Dr. Robert Corruccini, a forensic anthropologist; and John Foster, a former United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) coal miner and retired Washington County sheriff. Most of the team worked daily on the project, which was completely funded by the team. No external grants were sought.

The team relied on hundreds of maps, animations, 3D renderings, charts, graphs, and figures. For the first time, the integrative methods and geospatial technology would be used to find the massacre victims’ locations.

Additional help was offered to the team. Some local residents claimed the men were buried in a location outside the cemetery. Others said they could find the graves by “witching.” Psychics even offered to speak to the dead on the team’s behalf. All these offers were politely declined.

An Archive of Life and Death

To create, store, manage, analyze, and distribute the data the team had assembled, a custom enterprise geodatabase model was implemented and deployed on Microsoft SQL Server 2008. By versioning the data, the team could work on the model and the attribution of the many sections, blocks, lots, spaces, and markers. Data and maps were shared by publishing numerous services via ArcGIS for Server.

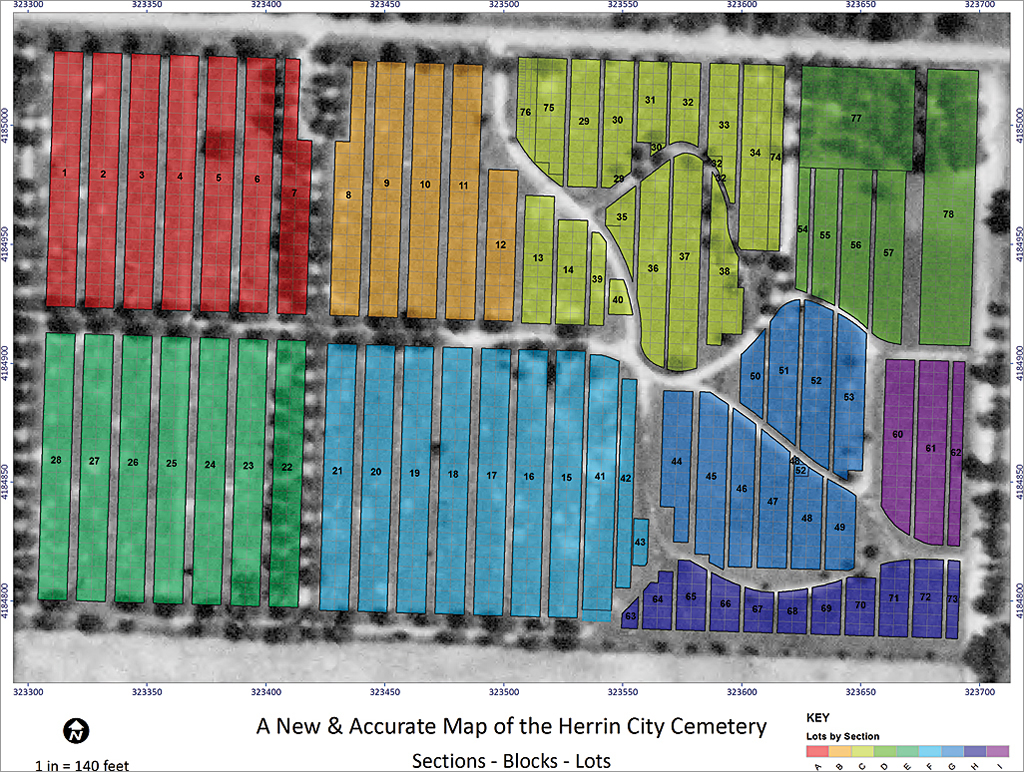

Taking an old, hand-drawn paper map, they built a GIS model of the cemetery’s parcel fabric from known dimensions. It was the conceptual design or ideal layout of the cemetery. Initially it acted as a template for analysis and modeling of interment and other data and was used to produce a single animation that would reveal the location of the potter’s field as a function of the behavior of its sextons over the cemetery’s long history.

The team produced the first accurate GIS inventory of the sections, blocks, lots, spaces, headstones, and associated interment records for the 25-acre cemetery. More than 9,600 interment records were modified from an existing genealogical database made available by the Williamson County Historical Society. This comprehensive repository of geographic data, empowered by ArcGIS, became the driving force behind the research.

Thousands of news articles from the period were reviewed. These account descriptions offered geographic clues and supported location hypotheses. The city’s cemetery records were studied; county recorder’s office records reviewed; and representative photogrammetry for every decade from 1938 to present, as well as period photographs, were obtained and scrutinized. From these resources, the team produced an accurate compilation of historical data for conducting research.

Field Surveys

In the field, accurate horizontal and vertical control was established using static GPS techniques. The data was processed through the National Geodetic Survey (NGS) Online Positioning User Interface (OPUS), which enabled positional precision on the order of millimeters—well above the accuracy and precision required. [OPUS provides access to high-accuracy National Spatial Reference System (NSRS) coordinates by upload of a data file collected with a survey-grade GPS receiver. The NSRS position for that file is returned via e-mail.] The team used real-time kinematic (RTK) GPS with a multiple-baseline solution and differential corrections provided by the Kara Company ReIL-Net on the NGS Continuously Operating Reference Stations (CORS) data to map headstones and acquire photographs of them contemporaneously.

In practice, although use of NAVSTAR [GPS satellite network operated by the US Air Force] generally requires signal acquisition from a minimum of four satellites on any given day to attain a position, there are specific intervals of time throughout the day during which satellite geometry and other factors permit recovery of precise positioning at survey-grade accuracies (i.e., centimeter level) when using RTK GPS.

By taking photographs and positions contemporaneously within these short intervals, during which survey-grade positions could be acquired, ensured collection of all headstones and attribute data. This strategy permitted the team to include attributes such as first name, last name, and date of death (when these were legible in photographs) back at the lab after processing the data.

The surface inventory allowed interment records tied to the conceptual model of the cemetery to be compared to actual interment locations in the field. Often, these locations did not agree. Conceptual designs seldom match reality, and the Herrin City Cemetery was no different.

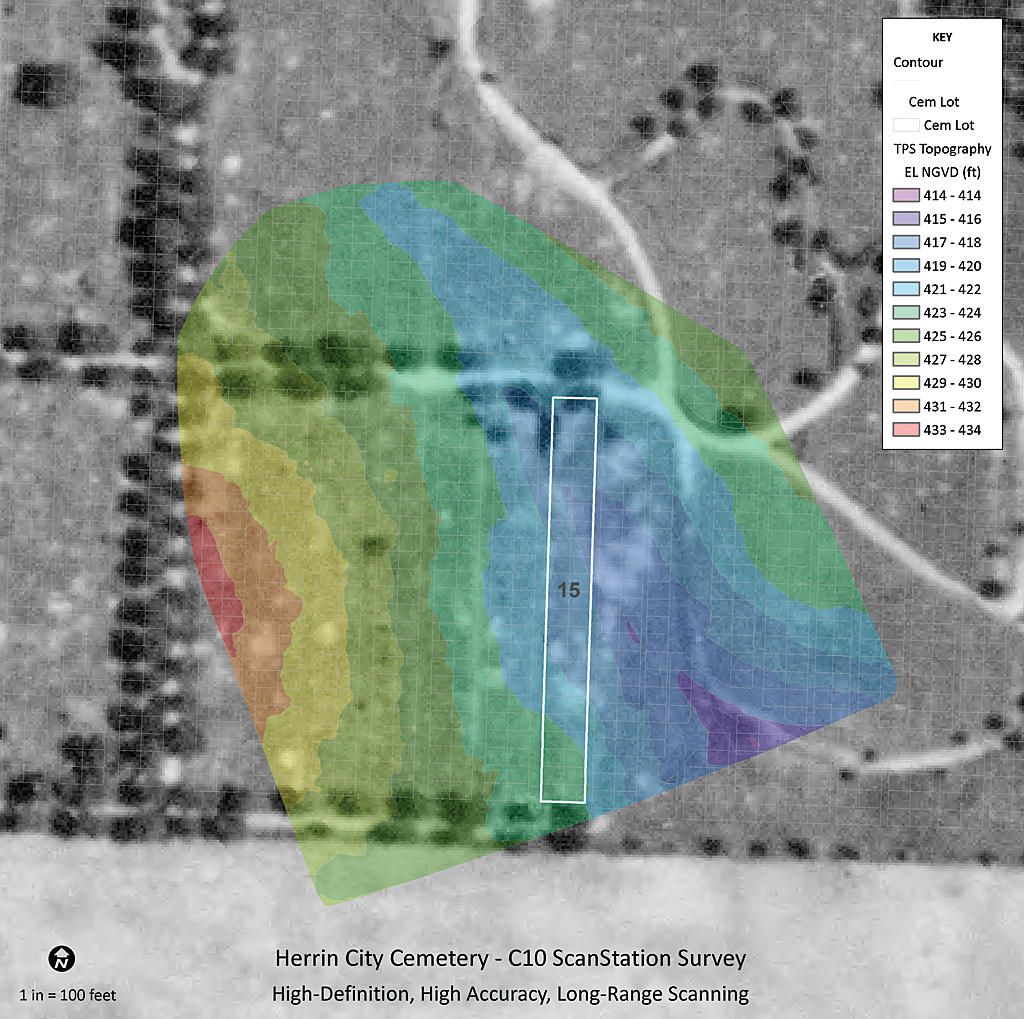

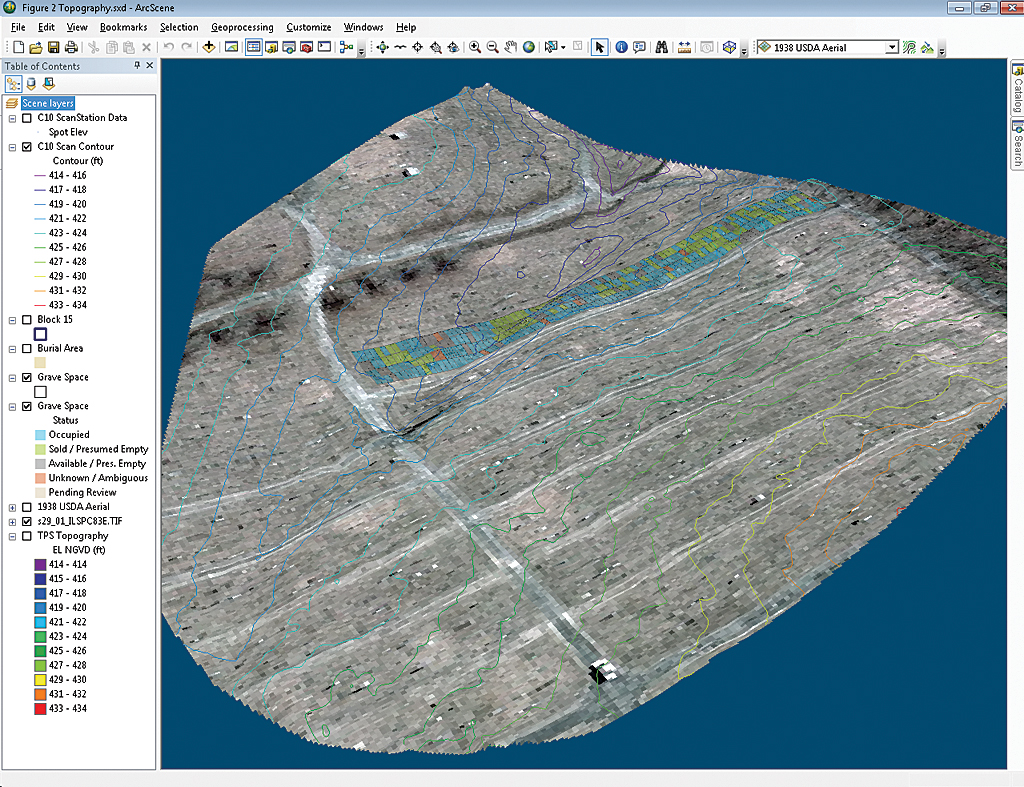

Using a high-definition, high-accuracy, long-range 3D scanner from multiple setups, an area encompassing 6.5 acres was scanned and detailed topography, headstone outlines, and imagery extrapolated from millions of cloud points obtained. This “microtopography,” processed using tools in ArcGIS 3D Analyst and visualized in ArcScene, offered insights into the locations of unmarked burial sites by illustrating small changes in slope and highlighting subtle surface depressions. Using this data, dynamic, virtual walk-throughs of the cemetery were created and made available using a simple web browser so the team could visit the cemetery virtually without having to physically go there.

A Cemetery Brought to Life

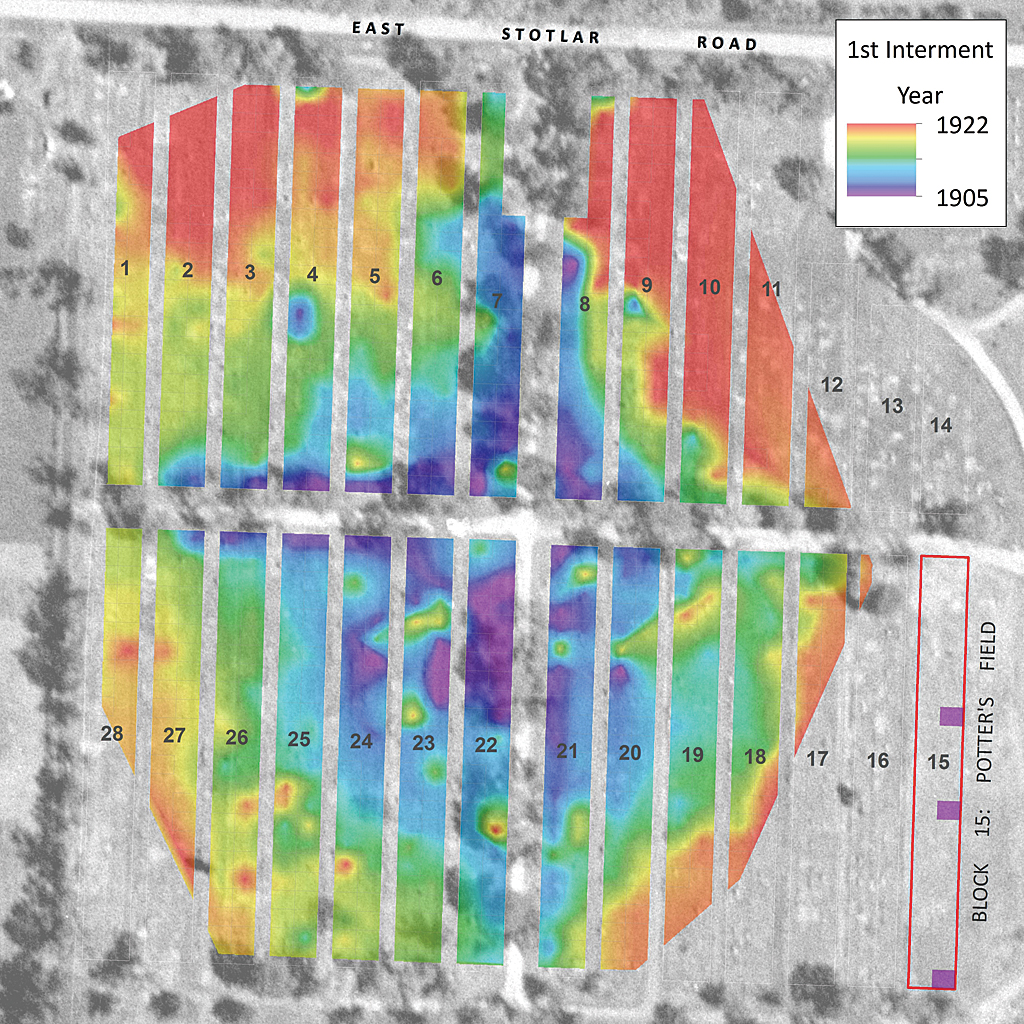

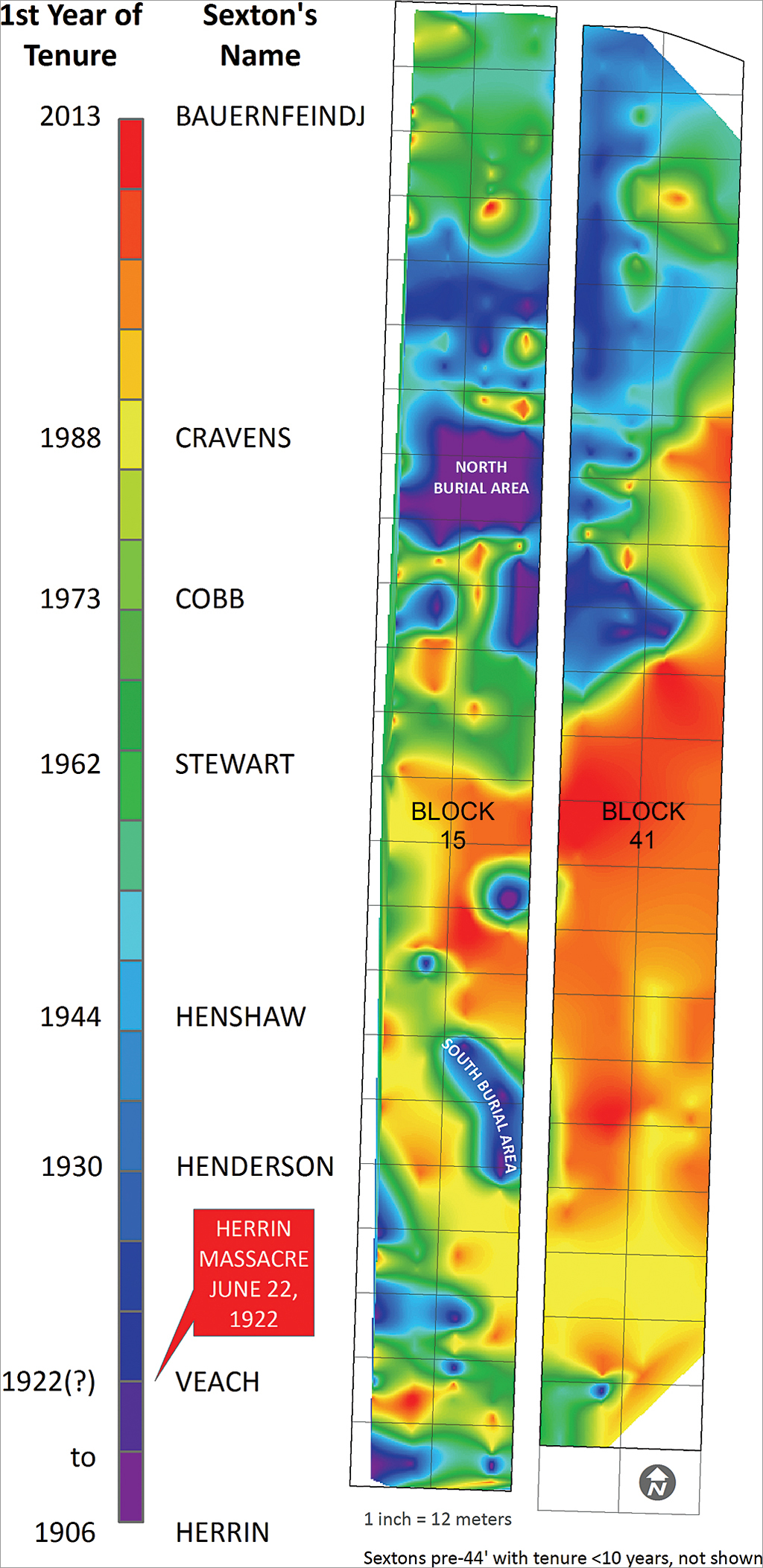

The GIS model offered a unique opportunity to locate the potter’s field through an animation of interments over the cemetery’s 108-year history. For example, one lot, 16 feet by 20 feet, held 8 grave spaces. Each grave space was 4 feet by 10 feet. Despite having interment data that was explicit to the grave-space level, the team decided to create an animation using the first record of interment for each lot to visualize the exponential growth of the cemetery with higher fidelity and without the hyperspecificity of space-level data. The grave spec for any one lot could be used independently over the lifetime of its availability. The simplified animation of the year of first interment in each lot demonstrated a less ambiguous patterning of the cemetery’s growth. The animation was supplemented with a continuous surface model of interments created using an Empirical Bayesian kriging interpolation model on the same variable.

An animation of interments between 1905 and the present revealed a predictable pattern of burial practices in blocks 1 through 28 with the exception of one block—block 15. The earliest burials (circa 1905) were at the top of a hill in the center of the cemetery. As new interments followed, these burials were located down-slope and radiating away from the center, continuing until all blocks were occupied. Block 15 however, was utilized irregularly, with contemporaneous and seemingly dispersed interments throughout its long history in a pattern typical of a potter’s field.

While the headstone survey provided information above ground, research of interment records provided information below ground for numerous unmarked burials, found mostly in block 15.

The Nail in the Coffin

After identifying block 15 as the potter’s field, a more explicit model could be produced for visualizing the activities of individual sextons in a manner that was not possible by simply looking at old interment record books. Although the city has a cemetery archive, the records for 1905 to 1929, the first 24 years of interment history, were missing.

To predict the location and associated years for these burials, the team compiled all known records of death and records of lot sales throughout block 15 and adjacent blocks 41 and 42. After creating a continuous surface model of this data, first by year, and then again resampled by decade, yielded a map of the hypothetical pre-1929 interments—and hence the probable location of the Herrin Massacre victims within a 30-year time interval. The team identified two distinct areas—one at the northern end of the potter’s field and another on the southern end—that were likely sites.

Geographically speaking, the GIS model indicated the historical burial array represented an area of one part in 58,000, relative to the 25-acre extent of the cemetery. The team’s work, based upon techniques of applied geography and GIScience, was sufficient to warrant excavation. It was time to propose this location hypothesis to city officials. After four years of intensive research, the team received approval from city council and began excavating the site.

Distinctive Interments

On November 12, 2013, the team discovered the first vault and coffin. Potter’s field interments in the Herrin City Cemetery were typical for the period: wood vaults, few coffins, scarcely any hardware, and no markers. However, the Herrin Massacre interments proved to be atypical.

Period photos and the observations of numerous reporters documenting the burial on June 25, 1922, played a key role in identifying the graves. In his Record of Funeral for the massacred men, the undertaker, Albert G. Storme, omitted any description of the bodies other than their number but noted the make, model, and other details of the coffins.

He ordered all the caskets from the Belleville Casket Company with the same specifications. Each was 6 feet 3 inches long and 2 feet wide, oval-topped with chamfered corners and eight sides, and painted black. The coffins had three pairs of opposing brass handles and cloth-lined interiors, and each was enclosed by a wooden vault—not typical paupers’ burials. Affixed to each was a plate reading At Rest. These plates were described in many news accounts of the period. According to news accounts of the burial, the men were buried in four rows of four, in an area roughly 16 feet wide by 40 feet long.

Vindication

The field excavations in November 2013 uncovered eight of the 12 victims. Excavations are scheduled to continue in the summer of 2014. The team’s hypothesis had passed the test—the graves of massacre victims had been located using GIScience and ArcGIS. A group of scientists and historians formed a research team that formulated several hypotheses, performed analyses, identified the likely location, and found exactly what they were looking for.

For more information, contact Steven M. Di Naso or Scott S. Doody.

About the Team

Robert Corruccini is a forensic anthropologist and distinguished faculty emeritus of the department of anthropology at Southern Illinois University.

John Foster is a United Mine Workers of America pensioner and a retired Washington County sheriff.

Vincent Gutowski is a geographer and distinguished faculty emeritus of the Department of Geography and Geology, Eastern Illinois University.

Grant Woods is a geography graduate student at the Department of Geography and Geology, Eastern Illinois University.

Acknowledgment

These individuals also helped with the project: Trevor Barham, operating engineer for the city, ran the backhoe at the site. John Bauernfeindj is the Herrin City Cemetery sexton. City Councilman Bill Sizemore was instrumental in gaining access to the cemetery.