Throughout her career, Hoang Chi Smith, the former GIS division chief for the California Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES), has been driven by a desire to help people and give a voice to those who don’t have one.

“I feel a lot of empathy,” she said, “because I’ve been a refugee. I didn’t have a voice, and I had no control whatsoever of my destiny.”

Born in Vietnam, Smith migrated to the United States as a refugee at the end of the Vietnam War in 1975—just days before the North Vietnamese government seized Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, and consolidated power. Her father was a colonel for the South Vietnamese Army, so had the family of nine stayed, they likely would have suffered political persecution, been denied economic and educational opportunities, or worse. Instead, they spent five weeks journeying by land, sea, and air to get to California via Guam.

“When we landed in Guam from Vietnam, the people from the Red Cross were there and the marines were there to hand out food,” she recalled. “They set up tents and tended to the sick, and it made an impact on me. I was 13, and that’s an age when things kind of form your view in life.”

Education was important in her household, so after completing high school, she attended California State University, Fresno, where she majored in industrial technology with an emphasis on manufacturing and design.

“I was always the only girl in the class and always the only girl after college to work in the field,” Smith recalled.

After graduating, she worked as an engineering technician for electrical connectors and did 3D drafting and design for aircraft components. She did a lot of work with CAD. It wasn’t until she was employed at a geotechnical engineering firm, Wallace-Kuhl & Associates, that she got introduced to GIS.

“Initially, it was a business need,” she said. “We did a lot of drawings and site plan studies for construction, for home development. Very quickly I learned that GIS provides spatial solutions and markedly improves data management because everything is location based.”

Smith ended up spearheading the GIS program there.

“We went from paper maps to creating geodatabases of all the sites,” she recalled. “And we tried to relate the data so it wasn’t fragmented.”

Soon, what had begun as a job requirement became Smith’s passion. She started taking classes in GIS to learn more about it. But when the 2008 recession hit, she was laid off.

She got a job right away with CH2M Hill, but less than a year after she started, the company sold her division to Critigen (and the entire company was later bought out by Jacobs). It was a tumultuous period, she remembered.

Around this time, in 2010, the 7.0-magnitude Haiti earthquake hit, and it struck a chord with Smith. She donated money to earthquake relief, but she wanted to do more.

“I felt a lot of empathy because I’ve been a refugee,” Smith said.

She remembers telling a senior manager at work that she was worried about being laid off again because her hours had been reduced, so she’d decided to take this opportunity to do more volunteering.

Smith started working with a local homeless shelter, which not only feeds visitors but also informs them about social services they can take advantage of.

“I saw the paper maps that they gave their clients. I was looking at [them], and I thought, ‘How on earth can people find their way to social services or bus stops and all that?’” she recalled. “I thought, ‘This is it.’ So I created a map for them and gave it to them.”

The project made Smith realize that she had some gaps in her mapmaking knowledge, so she went back to school to earn a certificate in GIS.

“My ultimate goal was [to work] with a big organization that would help people in need [during] disasters—man-made or natural,” she said.

Smith shifted her career toward GIS. She interned at the US Forest Service and did a student assistantship at the California Department of Water Resources. She worked her way into GIS analyst and technician roles at the county and state levels before joining Cal OES as a geospatial systems analyst.

Her first activation at Cal OES was the ongoing drought in the region. Each day for about six or seven months, she and her colleagues published seven or eight rolls of very large maps to send to the governor, the Cal OES director, and the different affected regions. She’s not sure if anyone ever looked at the maps. They seemed to be available just in case someone needed them.

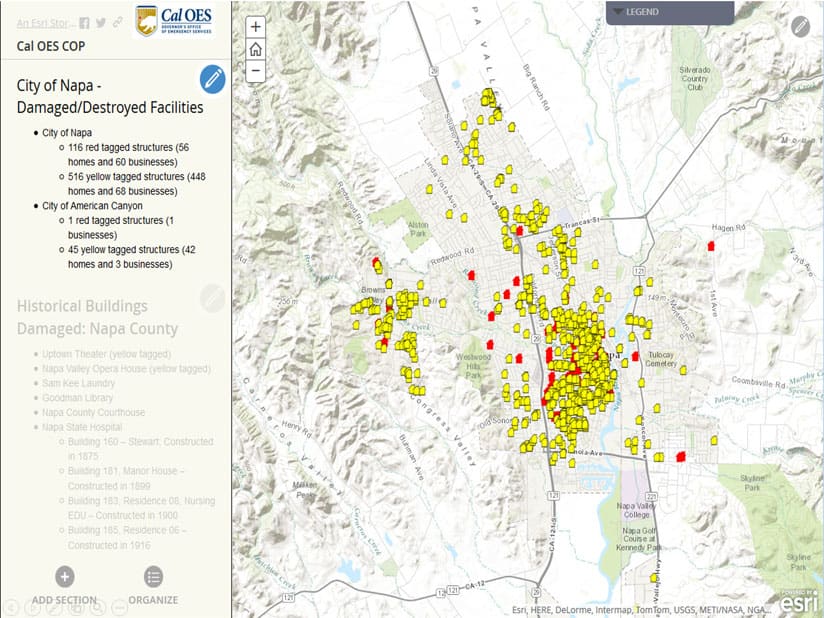

For a while, she kept her head down and learned a lot. But then the 6.0-magnitude Napa earthquake struck in 2014, and that proved to be a turning point. Her manager called the Esri Disaster Response Program (DRP) for assistance but then had to leave because of a medical emergency. Smith and her team were essentially on their own.

“We were overwhelmed. We didn’t have the capabilities. Everything was on paper,” she said. “When things like that happen, executives want to know what the impact is. And we didn’t have any way of summarizing the impact or coordinating the data. We didn’t know how to get things like damage assessments.”

Through the DRP, Esri sent technical marketing specialist Jon Pedder to help out.

“I introduced myself to him and said, ‘I’m the most junior person here, but I really care about this,’” she said.

Pedder showed Smith some tools that Esri had available, including Collector for ArcGIS, which Cal OES could apply to damage assessments, and the Esri Story Maps Journal app, which the agency could use to create a common operational picture of the situation. Smith was so enthralled by all this that, somewhat against convention, she took it to the chief of the state operations center and then the director of Cal OES. They decided to implement the technology immediately.

“That was my biggest milestone—to go from paper to digital to online,” said Smith. “After Napa, we had the authority and the ability to…set good examples, to say, ‘Here is a model of what we can do during an activation, and quickly.’”

When she eventually took over as the GIS division chief for Cal OES, Smith focused on building relationships and fostering trust among other agencies so they could share their authoritative data and work with GIS online. During big wildfires, for example, Cal OES worked very closely with CAL FIRE, so it helped if the two organizations had the same data. It was similar with the California Highway Patrol, since the law enforcement agency had maps that showed emergency escape routes and closure areas.

“We used a lot of diplomacy, held a lot of exercises together, and had a lot of meetings and functions,” Smith recalled. “I think that’s why it was really successful during my tenure there.”

Smith enjoyed working at Cal OES and felt like she was really helping people in need when fires, earthquakes, and other disasters displaced them in their own state. But she was increasingly feeling a tug to use her own experience as a refugee to be a voice for others.

For years, she had been writing a memoir of her experience growing up in Vietnam and being a refugee. At first, she’d intended only to give it to her American-born children to show them how different her life had been from theirs. But more and more, she felt like her story could resonate with other refugees and potentially be the voice that many of them felt they lacked.

“I felt like I had done my work at OES,” she said. “Could I have stayed and done more? Of course! But it’s my obligation to speak out because, if I don’t, maybe nobody will.”

Under her pen name, Hoàng Chi Trương, she published her memoir, TigerFish, in 2017. But she hasn’t left her experiences at Cal OES behind, nor has she abandoned GIS.

She recently published a children’s book, No Ordinary Sue: The Tale of a Heroic Pumpkin, which follows a pumpkin who escapes from a flood and finds herself helping others along the way.

“There are some questions in the back to encourage [adults] to talk about disaster preparedness with their kids,” she said. “If I hadn’t worked at OES, I wouldn’t have thought about the importance of publishing that book.”

In addition to writing and doing public speaking engagements, Smith stills makes use of GIS.

“I am working on some map journals to share with local groups who help…refugees from the Asian-American and Pacific Islander community,” she said. “We are not monolithic, and we have different challenges.”

Which is something she knows that GIS can help articulate.