Employing the Principles of Geodesign, Plas Newydd Farm Opts to Restore Biodiverse Habitats

“We’re approaching a problem in the loss of biodiversity comparable to climate change,” renowned biologist E. O. Wilson warned in a video recorded for the 2018 Esri User Conference. “We’ve jacked up the extinction rate [of species] at least 100 times.”

According to Wilson, natural ecosystems that are millions of years old are being erased swiftly—and irreversibly.

“Climate change, we can reverse that. But we can’t reverse the loss of three-fourths of the species on the earth,” he continued. “If we could save half of the earth’s surface in protected areas, that will give us security for 85 percent of the species.”

At a time when many landowners are jumping on the real estate development bandwagon, the Morgan family, which owns and manages the Plas Newydd, LLC, farm, has decided to restore and conserve 876 of its 1,650 acres of farmland to its native Pacific Northwest habitat.

But how can one family take more than half of its farm and return it to the biodiverse Columbia River floodplain it used to be? With geodesign, of course.

A Farm with Ecological Value

Just north of Vancouver, Washington, at the confluence of the Lewis and Columbia Rivers, lies the heart of Wapato Valley. First mapped by the Lewis and Clark expedition in the early nineteenth century, the explorers gave the area its name because of how dominant the herbaceous, arrow-shaped wapato plant was in the ecological and cultural landscape.

The land that constitutes Plas Newydd Farm has been used for agriculture since it was first homesteaded in the 1840s. Levees and dikes placed on the rivers in the early 1900s blocked native fish access to prime floodplain wetlands and off-channel nursery habitats. Since that time, road construction, farm infrastructure, and pasture management practices have further impacted many native plant communities and wildlife habitats.

When the Morgans purchased the farm in 1941, they sought to not only be productive farmers but also good stewards of the land. Over the last two generations, however, the amount of agricultural acreage in the area has declined and prices for agricultural and timber products have fluctuated wildly.

Given the land’s prime location, the Morgans have always faced pressure to sell or develop it. But the family wanted to sustain the land’s working spaces and preserve its ecological value. So the Morgans managed the farm for sustainable forestry and leased cattle grazing and duck hunting while searching for ways to remain solvent.

After looking into several options, the current generation of family owners decided that dedicating a large portion of the land as a mitigation and conservation bank would be the way to go.

Capitalizing on Natural Assets

In the state of Washington, when roads, bridges, railroads, buildings, utility assets, ports, docks, or other infrastructure are built or maintained, the companies and government entities doing the work have to offset the environmental impacts of that development. This is where mitigation comes into play, which falls to various regulatory agencies, including the state’s Department of Ecology and the US Army Corps of Engineers.

One goal is to maintain the size and function of Washington’s current—and very ecologically important—wetlands. To that end, these agencies approve mitigation bank projects throughout the state so landowners can sell mitigation and conservation credits to restore aquatic habitats on their properties.

In 2015, state and federal agencies issued a public notice to start the process of setting aside 876 acres on Plas Newydd Farm for mitigation and conservation. Now, staff for the Plas Newydd Conservation Program are working closely with seven federal, state, and local agencies to create the Wapato Valley Mitigation and Conservation Bank.

“A mitigation and conservation bank allows us to capitalize on our natural assets rather than selling them for development,” said Kelley Jorgensen, Plas Newydd’s president of conservation. “In essence, we’re banking on biodiversity.”

Geodesigning Renewed Freshwater Habitats

The proposed bank site is located in the middle reaches of the Lower Columbia River, where Willamette Valley, the Puget Trough, and the Pacific Flyway converge. This freshwater habitat, which is influenced by tides from the Pacific Ocean, supports incredible biodiversity.

The best way to improve the farm is to be on the farm. Listen to the land and pay attention to what it has to say.

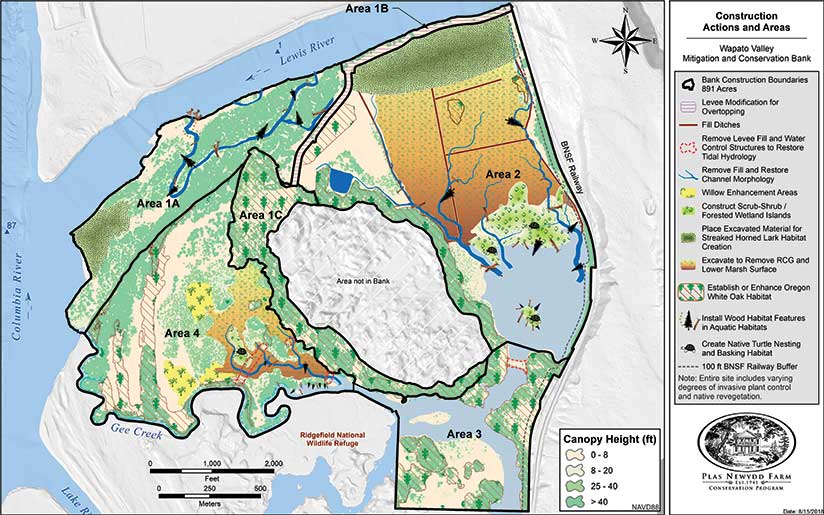

One of the design goals of the bank is to remove the man-made constraints that have been added to the landscape over the last 175 years. The objective is to restore natural processes to that area to the greatest possible extent, given the constraints of an ecosystem in which nearly all the usual disturbance regimes—flood and fire, for example—have been extinguished.

“We’re taking human-made constraints back off the land. We’re unbuilding,” said Jorgensen. “Humans love homogeneity, [but] nature loves heterogeneity. So we’re putting back messy things.”

To control what it could of this intentional mess, Plas Newydd Conservation Program staff decided at the outset to design the Wapato Valley bank using GIS. Going through the Esri Conservation Program, Plas Newydd received a grant that included ArcGIS Desktop, ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Spatial Analyst, and ArcGIS Geostatistical Analyst—all of which proved invaluable while the team was gathering baseline data, doing the initial site characterization, and putting together the design.

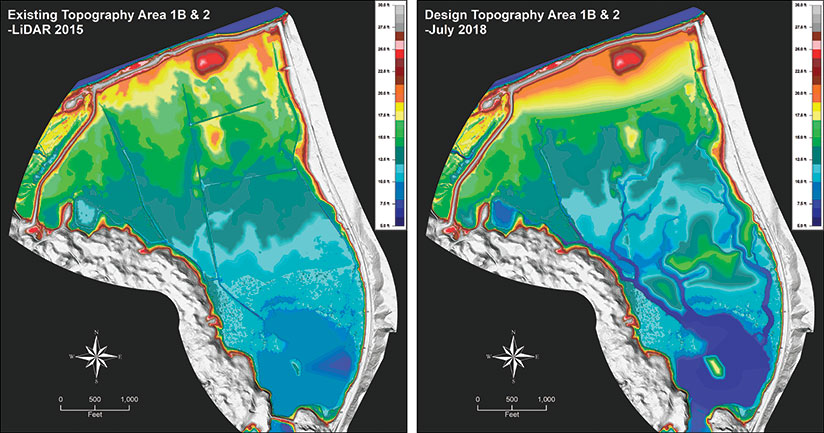

In this phase of the project alone, field staff generated more than 16,000 GPS points that reveal the exact elevations on the floodplain where different species thrive. They also produced several terabytes of additional raster and vector data that helped facilitate the design process and are contributing toward making predictive, elevation-based models of fish habitats. Using existing lidar data, the team specifically employed the ArcGIS Spatial Analyst extension in ArcGIS Desktop to create digital surface models (DSMs) and digital terrain models (DTMs) of the proposed mitigation and conservation area to examine grading options, restoration scenarios, hydrology regimes, planting plans, and various habitat change possibilities.

“Every aspect of the design goes through GIS to adequately display the information in a clear and clean way, allowing the diverse stakeholders to see the change on the ground without the need to translate CADD drawings,” explained David Morgan, Plas Newydd’s managing partner.

A Values-Driven Technology

Employing GIS has also allowed the Morgan family and Plas Newydd Conservation Program staff to conceive of the Wapato Valley bank in a way that puts the land and its habitats first and is mindful of the family’s values—both of which are the very core of geodesign.

“The best way to improve the farm is to be on the farm,” said Rhidian Morgan, a second-generation family manager on the farm. “Listen to the land and pay attention to what it has to say.”

Drawing on the family’s unique knowledge of the farm, as well as an extensive cache of historical documents and hand-drawn maps that stretch back to the early 1800s, the team is employing GIS alongside translational ecology. A team-oriented and action-driven applied science, translational ecology incorporates traditional and local ecological knowledge that’s typically held by nonscientists such as landowners, land managers, funders, and policy makers.

Given that so many people from various disciplines, backgrounds, and generations are so deeply involved with the project, GIS has been critical not only to gather and organize data about the land but also to communicate information about the Wapato Valley bank—in large part because of its visual nature.

“We use it with equal success to tell our story to those family members who own the land but live far away, family who are still local, the farm manager and farmhands, regulatory agencies, permit writers and the bank certification decision-makers, our future credit buyers, neighbors, the local community, funders, and lawyers,” said Jorgensen. “For everyone involved, this framework generated a profound appreciation for the complexity of both the social relationships and the hydrology and biology that drives and constrains habitat-forming and -maintaining processes in the Columbia River estuary.”

The result is a floodplain restoration design that will reinstate hundreds of acres of upland, wetland, and aquatic habitats—bringing biodiverse flora and fauna back to a place that has lost them. Juvenile salmonids, for example, will benefit from having a larger expanse of cold-waterfed, off-channel rearing habitats that allow them to feed and grow. Additionally, the team is creating a planting plan for the bank that encompasses more than 10 different plant communities.

“The development of this planting plan has been a dynamic, iterative process [that has adapted] to new field data collected on-site and [has allowed] us to take advantage of opportunities and avoid potential issues as they become known to us,” explained Karen Adams, Plas Newydd’s senior wetland ecologist and monitoring lead.

With the multiple layers generated during the baseline data collection and site characterization process—including ground and water surface elevations and soil, wetland, and habitat types—the team was able to map the layout of these plant communities. The layers also helped describe the types of restoration for these plant areas, quantify the changes they would experience (in size, extent, and makeup), and provide clear direction to the consultants who create the engineering plans for the Wapato Valley Mitigation and Conservation Bank.

“The efficiency of ArcGIS…permits us a level of responsiveness and ecologically sensitive design that would not be possible without these GIS tools,” said Adams.

Get on the Biodiversity Bandwagon

The success of the Wapato Valley bank lies at the convergence of geodesign and translational ecology. And thanks to GIS, combining the two specialties is working.

Plas Newydd is leading by example, demonstrating that there are opportunities to have a positive impact on biodiversity without “losing the farm.” The Morgans understand their property in a landscape context, and that has allowed them to not only avoid developing the property but also improve the land their family has loved by making biodiversity work for them.

If more landowners do the same, we can heed Wilson’s counsel and use geodesign and translational ecology to save some land in protected areas and provide security for 85 percent of species all over the world. It’s now or never.

For more information on this project, email Plas Newydd’s GIS/project manager and geologist Chris Watson at cwatson@pnfarm.com.