Like many coastal areas around the world today, the beaches in Chennai, India, attract large amounts of plastic debris. For teenage surfer and local resident Karan Chakravarthy, the presence of plastic at his favorite surf spots was distressing. So he decided to do something about it.

Chakravarthy joined other volunteers to collect trash with a nonprofit called Namma Beach, Namma Chennai (which translates to “Our Beach, Our Chennai”). In 2021, the organization removed 176,000 pounds of plastic waste from Chennai’s beaches. But Chakravarthy felt that more could be done.

He contacted his grandfather, Mandyam Venkatesh, who lives in San Diego, California, and obtained a $5,000 grant from Venkatesh’s Sunrise Rotary Club to further support Namma Beach, Namma Chennai. Through his grandfather’s Rotary connections, Chakravarthy also met Carl Nettleton, the founder of OpenOceans Global, a San Diego-based organization that employs geospatial technology and citizen science to help stop the flow of plastic to the world’s oceans.

Nettleton set up Chakravarthy with an ArcGIS Survey123 form that he used to record information about beaches in Chennai that are consistently littered with plastic. The data was then uploaded to the OpenOceans Global geospatial portal. Now, on the organization’s web-based Ocean Plastic Map, a red bull’s-eye symbol sits on India’s southeastern coast, and a pop-up displays information about the plastic waste found on Chennai’s beaches, including where it likely comes from and what is being done to clean it up.

Nettleton hopes that citizen scientists all over the world will do what Chakravarthy has done and record data for OpenOceans Global about beaches that are consistently fouled by plastic trash. In particular, he would like GIS practitioners to take the lead.

How Plastic Waste Gets to the Ocean

Eleven million metric tons of plastic reach the ocean each year, and that number could triple by 2040 if large-scale solutions aren’t developed quickly, according to research by The Pew Charitable Trusts and sustainability consultancy SYSTEMIQ.

“The common perception is that most ocean plastic is in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which is estimated to be twice the size of Texas,” Nettleton said, referring to the largest of five garbage patches in the world’s oceans.

However, according to a recent Florida State University study published in Frontiers in Marine Science, from 2010 to 2019, about 75 percent of mismanaged plastic waste turned up on beaches.

“Plastic ends up on shorelines because the majority of ocean plastic comes from land, and most of that comes from rivers,” Nettleton said.

OpenOceans Global seeks to identify how plastic flows into the ocean and accumulates on those shorelines. According to a study funded by the nonprofit The Ocean Cleanup and published in Science Advances, about 80 percent of plastic that traverses rivers and ends up in oceans comes from more than 1,000 rivers—many of which are in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Researchers found that small urban rivers in places with poor trash management practices convey the most plastic pollution to the ocean. But this doesn’t mean that the trash necessarily originates there. Many countries with upper-income economies—such as the United States, Japan, and France—outpace the rest of the world in plastic consumption and then ship more than a million tons of recyclable plastic overseas each year, often to places with trash management issues.

“We think there are ways to stop plastic waste from reaching the ocean if we know where it comes from geographically,” said Nettleton. “Even though the United States and other developed nations produce most of the plastic, the Florida State study found that 55 percent of ocean plastic reaches the ocean from five countries: China, the Philippines, India, Brazil, and Indonesia. If the Philippines sends almost 16 percent of the world’s plastic to the ocean via its rivers, as this study discovered, the world could focus on developing solutions for this one country and bring global resources behind it to get the Philippines as close to a zero ocean plastic contribution as possible. We could see which solutions work best there—whether it’s implementing river intervention technologies to stop the plastic from reaching the ocean, developing new products to replace plastic, or implementing new processes for trash management—and then replicate those models in other high-plastic polluting countries.”

A Global View of Where Plastic Pollution Originates

To get started with this ambitious project, the team at OpenOceans Global employed ArcGIS Online and ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World to develop a map that focuses on where plastic litters the world’s coastlines.

“You can click on the map and see the rivers of the world, major ocean currents, and a highly detailed point-in-time snapshot of ocean currents,” said Nettleton. “These tools help people better understand how plastic debris travels.”

Map users can activate layers that show the top 20 rivers that contribute plastic to the ocean and where plastic collects in ocean gyres. They can also see the survey data that citizen scientists contribute about plastic pollution on their local beaches.

Using Survey123 on their mobile devices or desktop computers, citizen scientists enter the beach or coastal area’s name, pinpoint its exact location on a map, upload an image that shows the waste accumulation, provide a description of the issue, predict where the trash is likely coming from, and record what is being done to solve the problem. They also enter their contact details and information about organizations they work with.

After an entry is submitted, a temporary red dot symbol automatically appears on the OpenOceans Global web map. A team at the organization then verifies the information and, if it all checks out, turns the red dot into a red bull’s eye, indicating that the coastal area is pervasively fouled by plastic.

“The way plastic has been approached is as a local problem—you know, ‘my beach has plastic on it, so I’d better not use plastic straws or plastic bags anymore,’” said Nettleton. “Well, that’s important. But there isn’t yet a global view of where that plastic comes from.”

The more entries that are contributed via OpenOceans Global’s Survey123 form, the clearer this global picture will be. And once OpenOceans Global has enough data points, the team will be able to distinguish the sources of plastic pollution on specific beaches—whether from rivers, stormwater systems, or inadequate local trash management—and develop new symbology on the map to reflect that.

“Knowing where the plastic originates helps identify solutions to prevent plastic from reaching the ocean,” said Nettleton. “For instance, placing barriers in small, local rivers can capture trash before it gets to the ocean. Theoretically, that will reduce the amount of plastic that ends up on beaches, and at a certain point, those beaches won’t be pervasively fouled by plastic anymore.”

Tracing Plastic Through the Open Ocean

For plastic pollution that arrives onshore via the open ocean, it is more challenging to identify the source. In the Galápagos Islands, whose once-pristine coastlines now gather plastic waste, an international research initiative called Plastic Pollution Free Galápagos employs a sophisticated forensic process to analyze plastic debris and determine its source. The initiative’s research suggests that more than 60 percent of plastic that ends up in the Galápagos Islands stems from mainland South America (mainly southern Ecuador and northern Peru), with about 30 percent coming from nearby fishing vessels and less than 10 percent from local towns.

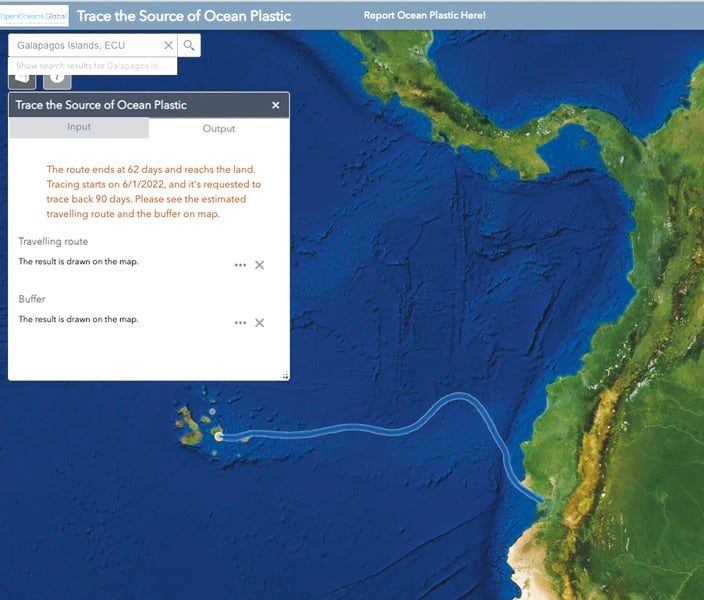

But not every coastal area has access to forensics data. So the team at OpenOceans Global worked with Jingyi Huang—who, at the time, was a student working toward a master’s degree at the University of Redlands and is now an enterprise analyst at Esri—to create a mapping app that traces plastic on coastlines back to its likely source.

The app employs Ocean Surface Current Analysis Real-time (OSCAR) data, which shows surface-level ocean currents, along with ocean current data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and satellite data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). App users can click on an area of the ocean immediately adjacent to where coastal plastic was found, and the app will create a route to its likely source. In the case of plastic waste in the Galápagos Islands, the OpenOceans Global tracing app aligns with Plastic Pollution Free Galápagos’s forensics research.

Before the app is included with OpenOceans Global’s publicly available web map, however, the tracing tool needs to incorporate wind and wave variables, since these affect how plastic is moves through the ocean. Huang plans to merge that data with the app’s existing ocean current data.

Citizen Scientists Are Key to Finding Solutions

In the future, Nettleton hopes that OpenOceans Global can use aerial imagery and artificial intelligence to identify where plastic is accumulating on shorelines.

“But as of now, the most effective and comprehensive way to collect this data is with citizen scientists using our Survey123 mapping tool,” said Nettleton. “Citizen scientists are critical to our success.”

He hopes that people who participate in data gathering will also form a community through OpenOceans Global where they can exchange ideas about how to keep their beaches free from plastic pollution.

“As solutions are put in place and shorelines are no longer fouled by plastic, we will turn the icons on our map green to show that the problem has been fixed,” said Nettleton. “That’s the ultimate goal.”