He led one of the largest international geospatial cooperatives in history. And his easygoing, unassuming nature is a big part of why it’s been a resounding success.

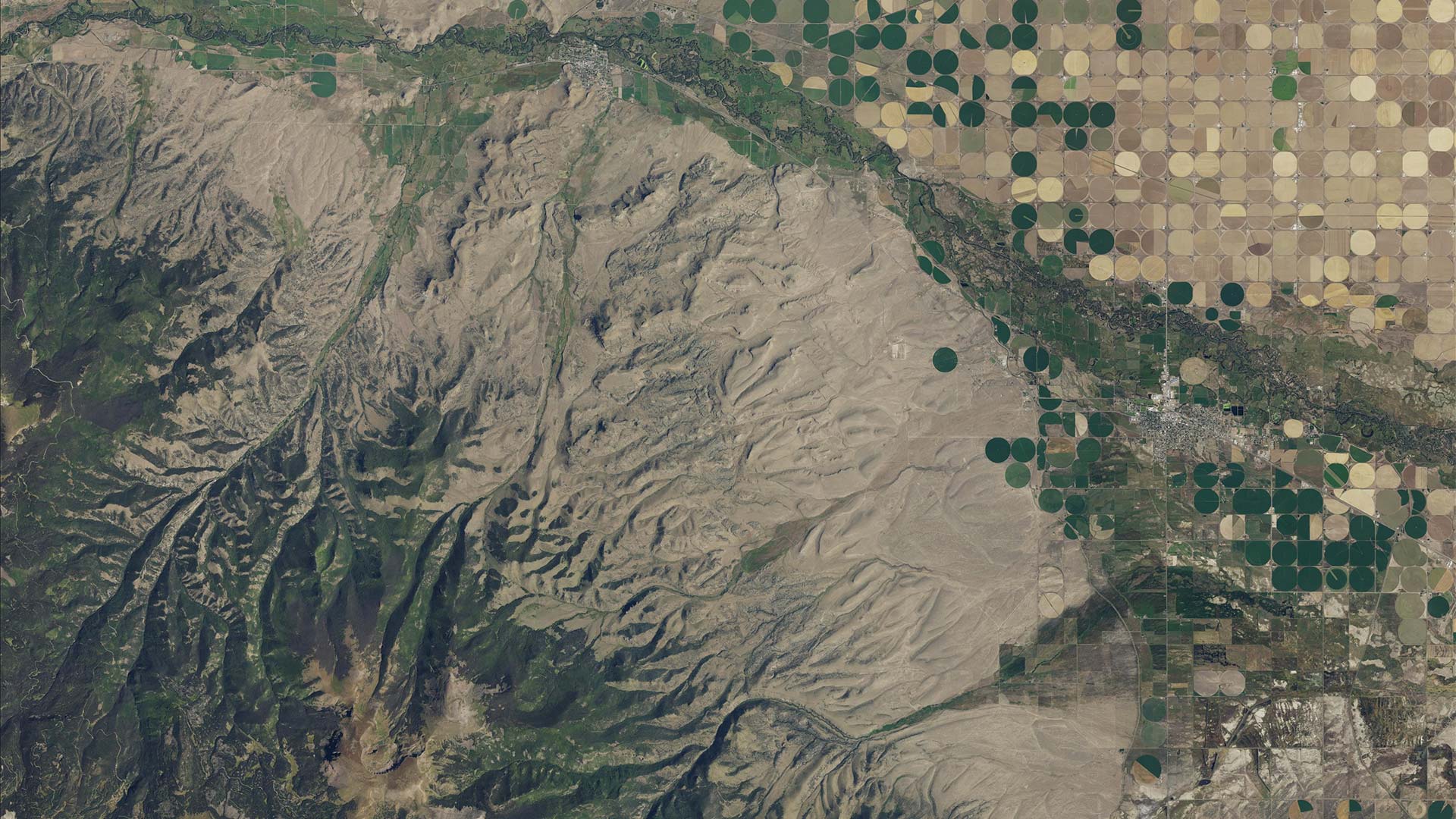

Marzio Dellagnello, who recently retired as senior geospatial intelligence officer for international programs at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), helped stand up and then managed the Multinational Geospatial Co-production Program (MGCP), a consortium of 32 nations that has created, updated, and maintained 5,300 one-by-one-degree cells of primarily 1:50,000-scale geographic data for key areas of interest around the world. That’s roughly the equivalent of mapping 27 percent of land on the globe with enough detail to carry out tactical operations, from military campaigns to disaster relief.

“It’s not easy to get 32 countries to work together. They all have their own national interests, their own data standards and standard operating procedures, and hundreds of military systems that need to be supported,” said Mark Cygan, director of national mapping solutions at Esri. “To get them all to agree on this and then produce more than 5,000 cells—that’s phenomenal. No one’s ever accomplished that. And now, as allies, they can all work off the same map.”

“There’s something about [Dellagnello’s] leadership style that just allowed him to get along with virtually everybody,” said Jack Hild, a former executive at NGA who was also instrumental in the MGCP. “The fact that he spoke a number of languages certainly helped a lot. But he had a really unique combination of having the technical knowledge and simply the right personality and leadership style to interact with all the governments involved.”

Born in Italy, Dellagnello moved to the United States when he was a teenager. He had always been interested in why human behavior happens in certain places, so he studied geography and cartography at the University of Kentucky.

“I was curious about population location, why cities are where they are,” said Dellagnello. “For example, you can trace an old buffalo trail and how the Native Americans used that, and then you can see that a road was made there. So we have highways that follow ancient roads. That type of information—why we use the lines of transportation and communication that we do and why this population lived where they lived—has always intrigued me.”

At a time when computers still required punch cards, Dellagnello was trained in manual cartography, “with scribers and all,” he said. But when he got his first job out of college at a small firm that produced maps for Kentucky’s coal mining industry, he did his work digitally.

“I really learned the whole process, from aerial photography and imagery to collecting features digitally,” he said about that job.

When he made his next career move and started working at the Defense Mapping Agency (DMA) in Louisville, Kentucky, Dellagnello went back to mapping by hand, producing 1:50,000-scale topographical line maps and joint operation graphics at the 1:250,000 scale. So he really came of age in the mapping industry as it evolved from manual processes to mostly digital systems.

The DMA office where Dellagnello worked eventually shut down as part of the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) program, so he was moved to Washington, DC. There, he continued to work for the DMA, which became the National Imagery and Mapping Agency (NIMA) and, later, the NGA.

“That’s where I started really doing GIS work,” he said.

He was part of the VMap Co-production Working Group (VACWG), a partnership of 19 countries that produced medium-resolution vector data of areas around the globe. The VMap Group expanded on the work of earlier cooperative programs at the NGA. These included the Inter-American Geodetic Survey (IAGS), which from the 1940s to the 1980s surveyed unmapped areas of Central America and South America, and the Digital Land Mass System (DLMS), which in the 1980s linked eight countries in creating a digital cartographic product for Europe.

“At the beginning, I was just a worker bee collecting features,” Dellagnello said about his time in the VMap Group. “Then I had the opportunity to engage with some European countries that were doing the same work, so I accepted a position in the international office.”

Eventually, he became the chair of the VMap Group and saw it through to the end of its mandate. The MGCP, which came about after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, was built on lessons learned from the VMap Group. At the time, the NGA was tasked with furnishing geospatial readiness anywhere in the world that the fight against terrorism might take the United States or its allies. But doing that alone was beyond the NGA’s mapping budget.

“The MGCP founders quickly brought 27 nations together to solve the organizational, resource, technical, sourcing, policy, and legal matters involved in producing and maintaining high-resolution geospatial data that’s functional for all their needs,” according to Cygan. “In less than two years, they went from having nothing to having a technical reference document in which they agreed on what all the features and attributes would be and what was needed to support defense forces in the field.”

By convening in this coproduction program, the 27 countries that initially got involved, along with the 5 that have been added in the years since, have produced more than they ever could have individually. And Dellagnello, with his determination to get things done in a collaborative and inclusive manner, embodied the ethos of the mission.

“One of the things [the NGA] mostly unconsciously tried to do initially was to not act like the 600-pound gorilla. We did not want the US to try to dominate this group. We wanted it to be a real team effort,” said Hild. “I believe, especially in retrospect, that the success of [the MGCP] was in taking that strategy. And Marzio was the heart and soul of all that.”

According to Dellagnello, most of what he did was deconflict various members’ interests to ensure that the data was produced according to certain specifications and delivered on time, when it was needed.

“We’re all on the same side, but…every country has a different way of working, different responsibilities, and even different fiscal years,” said Dellagnello. “Trying to get the funding in place for everybody to work and deliver the data was not all the same.”

One of Dellagnello’s main priorities was to ensure that each country was working on areas of interest that were valuable to it.

“For example, there are parts of the world where the United States may not have priorities but other countries do,” he said. “It was important to make sure that we paired up the right countries with the right areas of responsibility so the data was delivered in a timely manner.”

Since 97 percent of the MGCP’s member countries use Esri software, it was also important that the group’s data would work seamlessly with ArcGIS technology. Members of Esri’s ArcGIS Defense Mapping team are typically present in the MGCP’s technical meetings to ensure that the ArcGIS Defense Mapping solution fully supports the MGCP’s data standard.

“We have a symbiotic relationship with the MGCP, the NGA, and geospatial intelligence defense mapping agencies around the world,” said Cygan. “We support many different defense standards and models for data as well as for cartography, including the Topographic Data Store (TDS), the Topographic Map (TM), the MGCP Topographic Map (MTM), and others.”

It’s this kind of symbiosis, both within the MGCP and with outside partners, that has led many MGCP members to cooperate in other endeavors as well.

“When the Olympic Games were in Turin in 2006, I went to Italy, and I was able to work with Italian defense forces on the data and products that covered the area where the Winter Olympics happened,” said Dellagnello. “There was no need for the NGA to produce any data for that, since Italy was well-covered by high-resolution data in that region, but it was a collaboration that was a big success.”

And Dellagnello knows what makes a successful collaboration at the bilateral and multinational levels.

“You need to search for an equitable quid pro quo because you want everybody to participate,” he said. “You need to standardize production. Relationships are critical. Don’t be bound by convention. Look at the long-term focus rather than a very quick return. And remember that no single partner has all the answers.”

He credits these principles, along with contributions from everyone on the NGA team, with keeping the MGCP on course and ensuring that it continues to be improved on and strengthened today.