How GIS Helped Save a Playground Pachyderm

If there is one thing that elementary school students around the world can agree on, it’s the wonderful feeling of hearing the recess bell. After quietly sitting and learning in class, it signals freedom to run, laugh, and play with friends, usually outside in the fresh air.

But in Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe, Baobab Primary School had a 10,000-pound problem that prevented students from leaving their classrooms in June 2018. It seemed that a male African elephant wanted to share snack break by enjoying some baobab fruit from a schoolyard tree.

“The students’ safety was an absolute priority for the school,” said Andrea Presotto, an animal cognitive geographer and assistant professor in the Geography and Geosciences department at Salisbury University in Maryland. “Though largely docile, male African elephants are protective of their space and will become aggressive if threatened by humans.”

Luckily, the elephant was one that Presotto and her team at the Victoria Falls Elephant Project had been tracking using GIS. Knowing how African elephants move through space and, especially, how this elephant had been behaving in the community, they were able to execute a plan that would clear the schoolyard and save the elephant’s life. Presotto also used ArcGIS StoryMaps to clearly record her findings should the team ever need to use this method again.

A Familiar Visitor Becomes a Nuisance

Presotto has been using ArcGIS technology for cognitive geography studies for about 17 years. Normally, this discipline seeks to understand how humans perceive and interact with their environment. That’s how Presotto started out, using a hand-held GPS device to follow people around their small community and then analyzing the data points in ArcMap. About 15 years ago, though, Presotto adapted the methodology to study animals. She initially received support to apply her geospatial approach to capuchin monkeys in Brazil, which eventually led her to this opportunity to work with elephants.

Presotto now collaborates with Connected Conservation, an organization that tracks 15 male elephants in southern Africa by using collars that provide their locations every 15 minutes. Her team—the Victoria Falls Elephant Project—had been tracking the elephant that visited the schoolyard since July 2017. According to the data points visualized and analyzed in ArcGIS Pro, the elephant had made the town his home and was familiar to the community. But a year into the study, his daily schoolyard visits were putting children in danger.

Typically, people’s first response to a recurring incident like this is to euthanize the animal. Although that eliminates the imminent threat, it is inhumane and removes the elephant from important and costly research. It is extremely expensive to collar an elephant, and in this case, a whole year of data collection would have ended abruptly. Additionally, Presotto and her team never would have learned how to mitigate the problem.

Fortunately, when the school called the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority (ZimParks) to remove the elephant, the rangers noticed the collar. They were able to contact Presotto’s local project collaborator, Malvern Karidozo, to see about finding a solution that was at once compassionate for the elephant and safe for the children.

Cognitive Geography Turns Up the Heat

Having grown up on her grandmother’s farm, Presotto explored Brazilian forests with her father and has since lived a life committed to saving and protecting animals.

“One of our main goals is to demonstrate that there are alternative ways of dealing with elephant encounters,” she said. “The elephant was around the school for three days. On the third day, the children got too close to the elephant and, feeling threatened, it chased the kids.”

Rather than euthanize the elephant, ZimParks allowed Presotto and her team to try a cognitive treatment. The creative cure, referred to as “disruptive darting,” involved tranquilizing the elephant and applying a chili oil-infused wax to his trunk. In Zimbabwe, farmers have long used chili peppers to keep elephants far from their crops. Until Presotto and her collaborators from the Victoria Falls Elephant Project employed it in this situation, however, authorities at ZimParks had never used the treatment for animal control purposes.

It worked. When the elephant woke up, he associated the schoolyard with the trauma triggered by the chili wax and left immediately. Continuing to track the animal via his collar, Presotto saw in ArcGIS Pro that he avoided the schoolyard for more than two years—likely to prevent getting chili oil wax on his trunk again. And when he eventually did return, he only went within 250 meters of the schoolyard very early in the morning when the property was vacated due to COVID-19.

So the chili wax experiment was a success. It kept the town’s children safe and saved the elephant from an untimely death.

A New Kind of Success Story—With Lasting Results

With help from her research students at Salisbury University, Presotto wrote a story using ArcGIS StoryMaps to visually communicate the success of the experiment to ZimParks authorities and Connected Conservation, the project’s funder. Presotto likes how, unlike typical slideshows, StoryMaps allows readers to interact with the data on maps and zoom in closely to see more details.

“People question images much more than they challenge data,” said Presotto. “We find that our work is transparent to others when we use ArcGIS StoryMaps because they can visualize and interact with the data and gain confidence in the cognitive solution we’re proposing.”

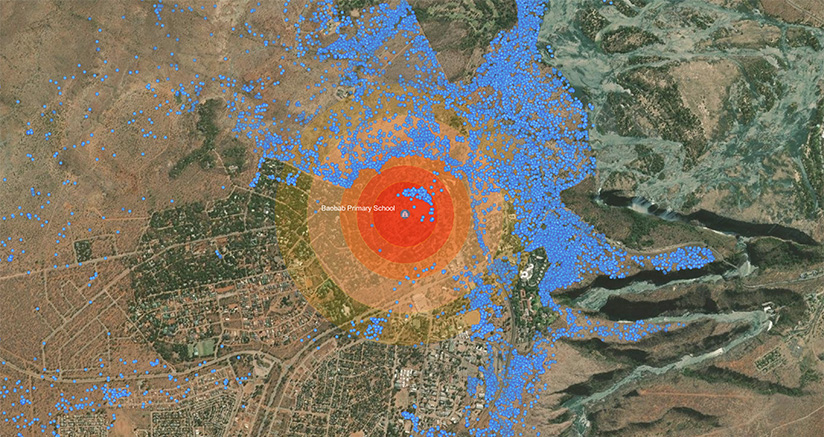

In Presotto’s story the data on the map clearly shows the elephant on school grounds prior to the experiment and at least 250 meters away afterward. The results were so effective that ZimParks allowed the Victoria Falls Elephant Project team to use this disruptive darting method of cognitive animal control again when another elephant was causing problems at the local airport.

-

The blue dots show where the schoolyard elephant had been tracked before receiving the chili oil-based cognitive treatment.

And there is more to come. Thanks to years of tracking these animals’ movements, Presotto and her team now have evidence that elephants travel through spaces they deem to be safe, mostly to avoid hunting activities. So she and the team are currently investigating how changes in human movement due to the COVID-19 pandemic have affected elephants’ cognition.

“People say an elephant never forgets because elephants have well-developed memories,” said Presotto. “Our hypothesis is that an elephant’s spatial memory is also well developed and that associations between certain spaces and emotional memories would prevent them from returning to traumatic event locations.”

The team already knows that when hunting activities are present, elephants stay away from those areas. But Presotto and her colleagues are looking into whether, during COVID-19—when Zimbabweans were under stay-at-home orders and there were no tourists or hunters in game reserves—elephants traveled equally over both protected areas and hunting-friendly game reserves.

“We talk about coexistence, but we rarely talk about how we’re going to do it,” said Presotto. “Technology illustrates how humans and animals can share this space.”