How the General Public Can Regain the Thrill of Scientific Discovery

Science means “knowledge” in Latin (scientia), with modern definitions focused on obtaining this scientia through systematic observation and experimentation to learn about the natural world.

This sounds straightforward. Why, then, is science met with such controversy and unease when presented to the general public?

This stems from a basic misunderstanding of how science works and what we can do with this knowledge. Mistrust may arise from poor education, media sensationalism, or stigma. As an educator myself, I have been shocked by students claiming that they don’t like biology because it is not hands-on. This grossly inaccurate perception is due to a lack of experience actually doing science, a consequence of focusing on testing memorized facts rather than on the development of critical thinking skills.

Many other students (and adults) state that while scientific topics are interesting, they just can’t think like scientists. I remind them that children display an innate scientific mind by constantly observing, manipulating, and testing their deductions to infer general principles that help them understand their surroundings. Sadly, this early application of the scientific method is often lost and many are scared away from the sciences.

But the public’s understanding of science can be greatly improved. One way to do this is by including people in the quest for scientia as citizen scientists.

Citizen science—the involvement of interested members of the public in collecting and/or analyzing data for scientific projects—is not a recent phenomenon. Bird watchers have formally contributed avian observations to the annual Christmas Bird Count since 1900, five years before the United States’ National Audubon Society was even officially founded, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology currently receives an average of 1.6 million bird reports per month through its eBird web tool. I have also been involved with citizen science for more than 20 years, working with Earthwatch Institute-funded projects to involve volunteers in investigating human impacts on marine mammals.

This rich history of citizen science is now being enhanced considerably. The widespread availability of mobile devices has enabled the development of apps that can easily include the public in generating important data to monitor populations, climate, and other natural phenomena. Not only can this improve the public’s understanding of both scientific concepts and methodology, but it can also directly benefit researchers whose monitoring projects—which are essential for conservation—are often made more difficult by lack of funding and increased expectations.

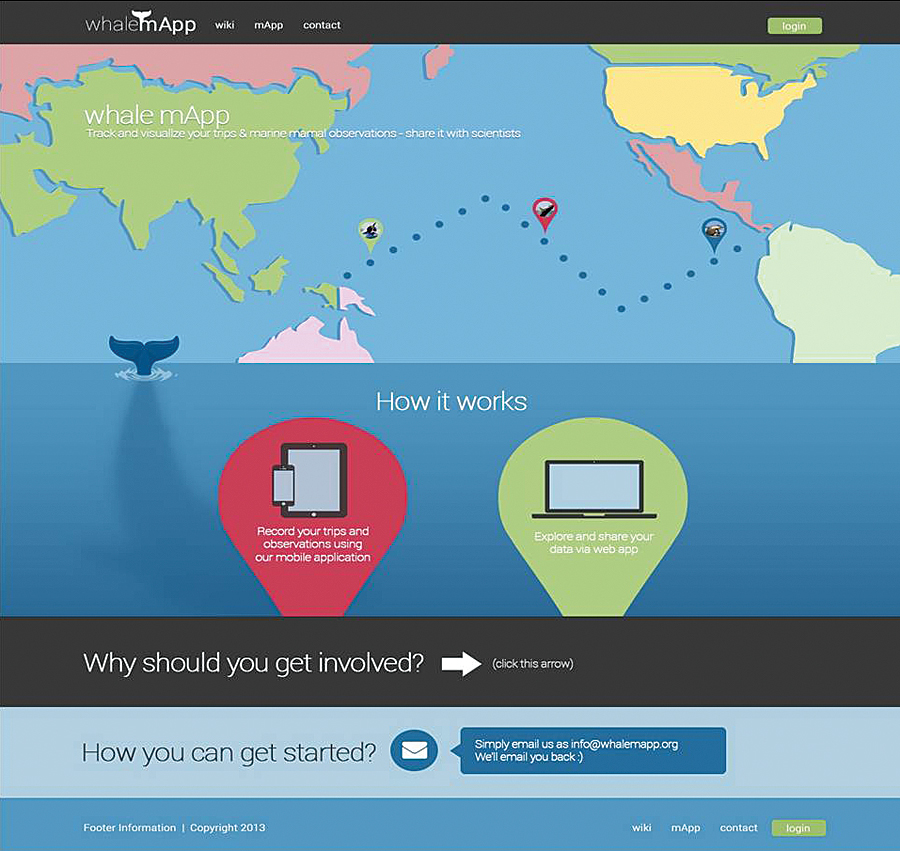

In 2013, I launched just such a project. With funding from the California Coastal Commission, GIS developer Melodi King helped me create Whale mAPP, a web- and mobile-based application that uses GIS to allow anyone to monitor marine mammals anywhere in the world.

Many marine mammal species are endangered or threatened, and baseline data is lacking for most populations. Millions of people observe whales every year, and these encounters are often recorded with photographs and videos. Yet this information is rarely shared with anyone other than a few friends and family members.

Whale mAPP allows anyone equipped with a GPS-enabled Android device to submit sightings of marine mammals to Whale mAPP’s website, whalemapp.org, and share their observations via an online geodatabase that is freely accessible to researchers and the public. The website displays the sightings in an interactive map along with photos, video clips, graphics, and educational details on different species and conservation efforts.

In the classroom, students can further utilize GIS to view marine mammal sightings and locations, formulate hypotheses, and then test their conjectures using the collected data. This develops the students’ scientific inquiry, spatial reasoning, and critical thinking skills while increasing their knowledge of the natural world.

To date, around 100 Whale mAPP users have collected more than 2,000 sightings from over 330 surveys in the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean, documenting more than 25 different marine mammal species. With marine mammals acting as charismatic megafauna, people are also enticed to learn more about marine life.

When citizens are directly involved in scientific research and recognize the relevance of their work, they are inspired to be passionate about and dedicated to conservation. For instance, when volunteers on my Earthwatch project observe plastic trash scattered amid a pod of dolphins, those people are likely to make positive changes in their own actions.

Community members with a renewed appreciation for the thrill of scientific discovery are invaluable to scientists as well. Citizen scientists collect new data and expand the geographic coverage of a study—all for free. Although some scientists question the reliability of volunteered data, this is easily managed by providing appropriate training, outlining clear expectations, and using technology that reduces the number of details that must be reported manually (e.g., location, date, and time, which can be automatically recorded by mobile devices) and requires data entry verification (e.g., photo submissions so scientists can confirm recorded species).

The growing trend of conducting citizen science projects like Whale mAPP is a positive force that provides necessary long-term data and promotes collaboration between researchers and stakeholders—two key components of successful conservation efforts. Moreover, empowering citizen scientists may reduce the gap that has historically divided the public, researchers, and policy makers in environmental management efforts. Collaborative projects enable scientists and citizens alike to recognize our shared mission as seekers of scientia, given that we are all, by our very human nature, scientists.

About the Author

Dr. Lei Lani Stelle is an associate professor of biology at the University of Redlands in Southern California. She is also the principal investigator for the Earthwatch Institute expedition Whales and Dolphins Under the California Sun, which monitors marine mammal behavior along the coast of Southern California. Whale mAPP can be downloaded for free.