The 2018 results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) are in. The good news is that we now have access to the most up-to-date information on how well eighth grade students in the United States understand geography. The data is ready and waiting to be shared, analyzed, and understood.

The bad news? The results aren’t great. Compared to 2014, the average geography score in 2018 on the nationally representative exam dropped by three points, and neither of these scores differs significantly from the first NAEP geography results, which came out in 1994. The latest figures show that only 25 percent of students performed at or above the NAEP Proficient level of understanding, while 29 percent tested below the NAEP Basic level. US students’ collective understanding of geography is insufficient, and it’s not making progress.

Meanwhile, the geospatial tech sector is booming. The geospatial services industry generated $400 billion in revenue in 2016, according to a report from strategy and economic advisory firm AlphaBeta. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 6 percent job growth rate for geoscientists from 2018 to 2028, which is in line with average growth rates for other fields. So the geography-adjacent job market is keeping pace with other industries, yet students’ understanding of geography in the United States is flatlining.

The NAEP exam framework covers geography’s basic components by testing the content areas of space and place, environment and society, and spatial dynamics and connections. These components recognize that geography education involves much more than identifying state capitals. However, the entirety of geography’s reach can be difficult to account for, since students can’t gain a comprehensive understanding of most other subjects without incorporating a geographic perspective.

In the geography community, the interdisciplinary nature of our subject is both a blessing and a curse. While it is clear that teaching with a geographic perspective adds value to other subjects, geography constantly runs the risk of blending into the background and losing its credibility as a stand-alone subject.

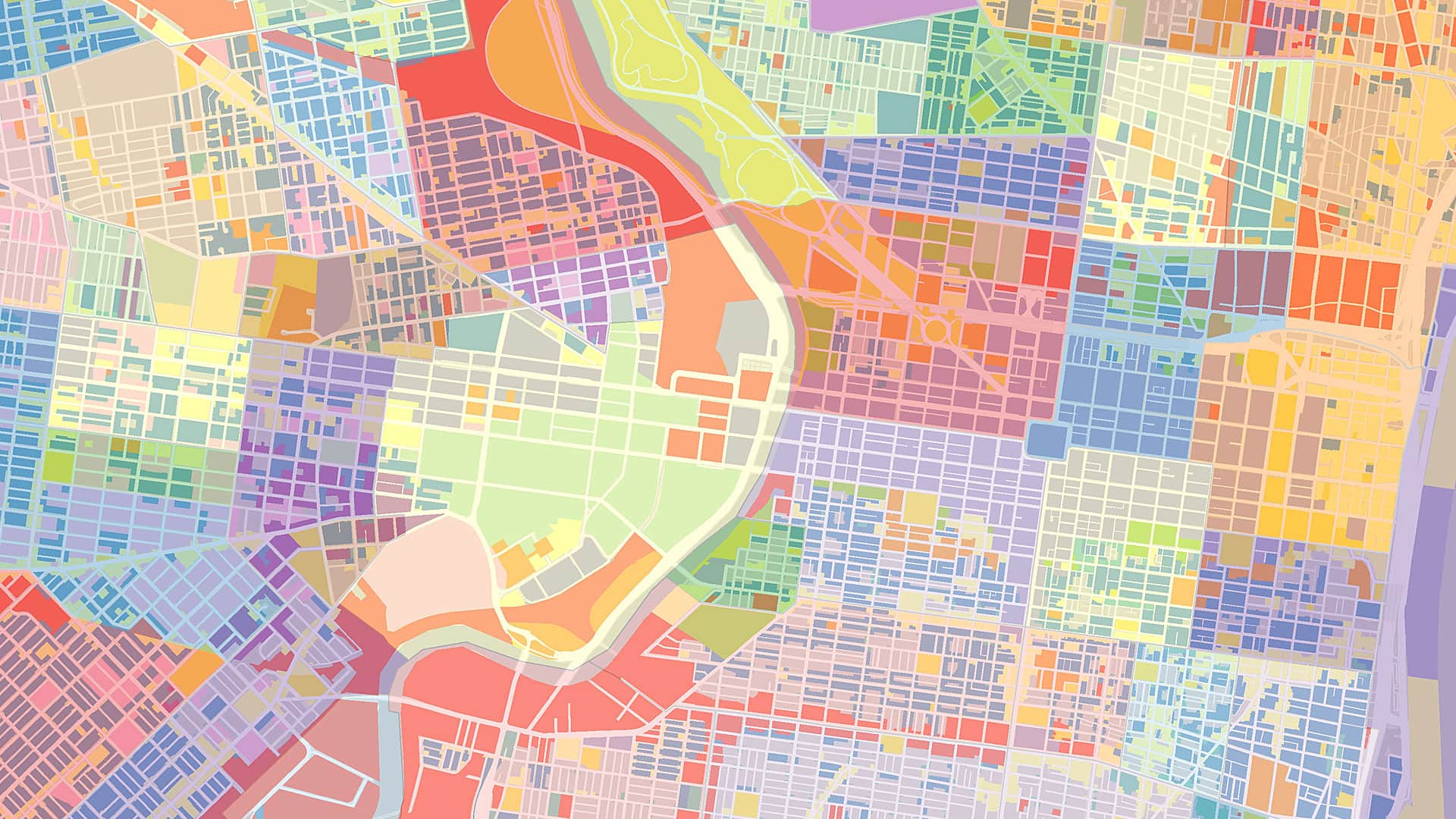

But geography stands alone as a discipline for many reasons, one of which is that it grants students a basic yet critical skill: the ability to read a map. The power of being able to understand a map during early education is a ticket to seeing parochial problems through a global lens and imagining solutions that extend far beyond the classroom. A student who has the capacity to critically analyze and understand a map will carry that for a lifetime. And with the ever-growing expanse of data and information available from disparate outlets, being able to sift for reliable sources and comprehend visual analyses is an essential skill.

As access to information grows, so, too, does the availability of visual displays that help us make sense of it all, and our next generation can’t be expected to cut through the noise without the underpinnings of a geography education. It seems that a shared goal of the GIS community should be equipping grade school students with the basic building blocks they’ll need to understand the world from a geospatial perspective.

If this commitment seems self-evident, then consider the importance of accountability. National-level assessments compel us to take a hard look at the makeup of our future populace. We can find dozens of reasons to support K–12 education and make promises to do better by students, but how can we achieve any of our goals without an honest evaluation of their achievements?

K–12 education can and must develop students to meet the demand of a booming GIS and geoscience job market. Already, the geography community heavily supports and advocates for geospatial critical thinking in K–12 curricula to prepare students for college, careers, and beyond. But our measure of progress is at risk. Due to a recent decision by the National Assessment Governing Board, geography assessments have no future on the NAEP schedule. As it stands, 2018 will be our last and most recent nationwide accountability check on our commitment to K–12 geography education.

We cannot build a geoliterate nation without identifying current gaps in student achievement. It is up to our elected officials and governing institutions to reemphasize and reimagine comprehensive achievement measures so we can change course as needed while continually striving to build a future generation as capable as the GIS technology waiting at its fingertips.