Versioning, Modeling, and Satellite Imagery Allow Conflict-Weary Country to Update Cadastres and Ensure Accurate Land Rights

During the decades-long conflict, many poor farmers in Colombia lost their land. However, due to the actions of former president [Juan Manuel] Santos, we are settling that historic debt, and land is no longer the fuel of war.

Inequality in landownership has persisted in Colombia since the country won its independence from the Spanish Empire in 1819. To pay for the massive war debt it incurred, the newly sovereign nation quickly sold off vast tracts of poorly documented public land, which often ended up in the possession of already wealthy landowners.

During the mid-1960s, guerrilla groups formed—most notably the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (known by its Spanish acronym FARC). These groups existed to promote greater equality throughout the country, but they fast became a polarizing force. This exacerbated political and social problems throughout Colombia, particularly in the rural areas, where guerrilla or opposition paramilitary groups often controlled villages and their surrounding lands after forcibly displacing the original landowners. Over the course of its six-decade duration, the Colombian Conflict resulted in 260,000 deaths and the displacement of 6.9 million people.

In 2010, former Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos announced in his inauguration speech his intention to return the land to those who were displaced by the Colombian Conflict. “It is not only an inescapable historical debt, but it is also a first step towards the construction of peace in the rural areas of the country,” Santos said.

The amount of disputed land totals 7 million hectares (17.3 million acres). This includes private properties and vacant and unclaimed land.

The following year, Congress approved Law 1448, the Victims and Land Restitution Law, which specifies the legal procedure for restoring lost land to victims who were forcibly removed from their properties. The procedure consists of two parts: one is administrative, which includes formally registering the land claim, and the other is a judicial appeal for restitution.

“The Land Restitution Law is one of the most important acts of the Colombian government in providing a lasting solution to the humanitarian crisis precipitated by the decades-long conflict,” said Ricardo Sabogal, former director of Unidad de Restitución de Tierras (URT), Colombia’s land restitution office. “It is an effective administrative and judicial mechanism that resolves, in a just manner, the complicated issues for the millions that were displaced from their land. It also encourages lasting peace and a consolidation of democracy in our country. The process consists of both an administrative step to formally register the land claim by the displaced farmer and a judicial action to resolve the land restitution claim made by both parties. In this sense, it is a combined process because it includes involvement by both the country’s executive and judicial branches.”

The URT performs the administrative procedures. The office receives, reviews, and makes a determination for all property claim applications. The National Land Agency then officially records the disputed land, which is an essential legal step in the restoration process.

“Because of the well-known informality regarding land possession in Colombia’s rural regions, Law 1448 also specifies that the URT must physically and legally define those properties that did not previously have cadastral or registry information associated with them so that they could be included in the records of the Oficina de Registro de Instrumentos Públicos (ORIP), the nation’s land registry authority,” said Sabogal.

Fully complying with this requirement demands using GIS technology, which has proved invaluable in helping the URT collect and analyze data that identifies distinct properties and specifies their precise location and size.

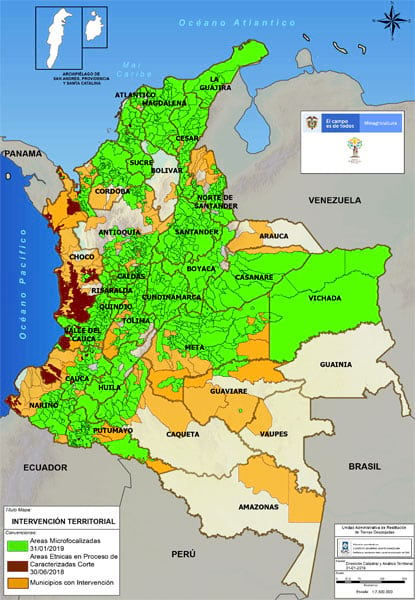

“Law 1448 stipulates that in order to collect information for restitution requests, it is necessary to first examine the available institutional information, such as ownership records, for the physical identification of the properties,” Sabogal continued. “Unfortunately, the rural cadastral property information is not the most reliable. According to the Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social [National Council of Economic and Social Policy] document of 2016 (CONPES 3859), 28 percent of the national territory does not have cadastral records, and 63.9 percent has outdated cadastres, which totals 722 municipalities. Also, among those 187 municipalities in the country identified as having a high incidence of armed conflict, 79 percent do not have basic cadastral information. The document further states that only 41 percent of the national territory has appropriate basic cartography at a scale needed for technical cadastral work. Added to this is the fact that, as a rule, the cadastre only identifies those who have some sort of document indicating an affiliation with a property, which excludes the majority of land claimants.”

To establish landownership, the URT collects data in the field and gathers historic information concerning each property’s years of abandonment or dispossession. Staff from the URT also take a tour around the boundaries of the property along with the applicants and their neighbors to determine accurate dimensions, boundaries, terrain details, and/or conflicts that are added to the evidence presented to the restitution judges. The URT uses satellite imagery and aerial photographs as well to conduct cartographic and cadastral archaeology, which helps the office establish property boundaries at submeter precision.

For applicants going through the administrative and judicial processes of recording a land claim, the use of GIS technology has played a significant role in validating the size, location, and ownership of each property.

“Technical and cadastral professionals from the URT, with assistance from Esri Colombia, are using ArcGIS to design methodologies to capture, structure, define, analyze, and exchange geographic information to determine the correct identification of an applicant’s land,” said Helena Gutiérrez, president of Esri Colombia SAS, Esri’s official distributor in Colombia. “The process involves the creation of a sequence of versions of the property as the investigation progresses. The process of this technical adjustment of the mapped polygon representing the property is called its ‘cadastral life.’”

“The URT has created a data portal using ArcGIS Online to provide easy access to geospatial services in support [of] this work,” said Jorge Bonil, the URT’s cadastral technical director. “In addition, we used ModelBuilder to create an automated reporting application that accesses and processes massive amounts of information from multiple sources and performs various analyses on that data. The tool identifies conflicting claims for the same land, claims in protected areas, unusual economic activities related to a particular piece of land, identification of the licensing or construction of infrastructure and energy production, and so on. Reports from these analyses are then generated for the administrative and judicial procedures.”

The land restitution initiative also uses thematic cartographic data produced and maintained by different Colombian governmental agencies. This includes data on national protected areas; mining and hydrocarbon extraction; road and energy infrastructure construction; strategic conservation, such as wetlands of international importance; government land usage and planning; land mines and unexploded ammunitions; and proprietary information prepared by the URT, such as applications for micro- and macrozones.

In addition, the URT employs satellite imagery and aerial photography to determine access routes to specified properties and the physical characteristics of the landscape and topography. For land disputes, it is sometimes used to divide parcels and determine equivalent land assets. Imagery analysis also helps the URT ascertain the status of collective territories and current land use.

“The restitution laws have set an important precedent for the availability and exchange of information among the government agencies,” Gutiérrez pointed out. “It has changed the institutional perspective towards sharing information by highlighting common objectives, which strengthens our government.”

Previously, she said, getting access to government data was complex from both a technological and legal standpoint.

“As part of the land restitution program, the URT participated in the development and testing of the LADM-COL model for land administration,” explained Gutiérrez, referring to a version of the international Land Administration Domain Model (LADM) standard that was adapted for Colombia. “This has allowed us to test and adapt those workflows needed for the supply and delivery of cadastre information within the established standards that should be included in the procedures implemented by the government.”

“The application of GIS technology to the process of land restitution assures that the land restored to its owner has been accurately identified and documented for legal inclusion in the land registry database,” added Sabogal. “GIS also helps with identifying the ways the property is related to nearby land to determine potential environmental implications, mining and energy production, and infrastructure policies—thus guaranteeing a proper use of the land without impacting the regulatory frameworks of other policies. It has also allowed us to perform geostatistical modeling to determine trends and explore scenarios so that we can develop land administration polices using more accurate data.”

The second, judicial stage of the process is carried out by judges who specialize in land restitution proceedings. Judicial authorities decide if the claim is legally and materially admissible, in which case the property is included in the Superintendence of Notaries and Registries. In cases where restitution of the property is impossible, the judges have the authority to order compensation in favor of the victim or in favor of third parties, as long as their actions were done “in good faith.” The government has processed 1.5 million hectares of land so far with a goal of processing 100 percent of the land restitution claims in the next four years.

The URT also has an important role in these judicial proceedings because it provides free legal representation to victims who request it. As part of this service, the office created a Mobile Victim Attention and Orientation Unit. Representatives from the National Victims Unit, the Public Defender’s office, and the Ministry of Justice drive a custom-made vehicle into rural municipalities to provide legal aid to people who have been displaced. This ensures that their interests are being respected, as specified in the law.

The land restitution process in Colombia not only provides legal services to thousands of displaced people, but landownership also allows them access to credit that can help them further develop their land. In addition, as owners of their land, they pay taxes on it, which helps improve government budgets.

“The speed in applying Law 1448 to the land restitution process has gained a level of success that has never been achieved by any other judicial mechanism in the country,” concluded Sabogal. “This has been made possible due to the foresight and determination of our government and its implementation by various agencies. It is important to remember that some of this work was carried out in the middle of the armed conflict, which created a unique series of complexities and difficulties in its implementation.”