At 3:54 a.m. on November 26, 2019, a 6.4-magnitude earthquake jolted people awake across central Albania. It was the most powerful earthquake to hit the southeastern European country since 1979—and its deadliest. Fifty-one people died, and approximately 2,000 were injured.

The destruction was extensive, especially in Durrës, the town closest to the epicenter. About 900 buildings in the coastal city were damaged, and many, including the seven-story Vila Palma hotel, collapsed.

“We were in a panic situation,” said GIS specialist Glen Olli, who works for Esri’s official distributor in southeastern Europe, GDi. His office, in Albania’s capital of Tirana, is located about 25 miles from Durrës. “It was a workday, so as soon as we got to the office [later that morning], we grabbed our laptops and went outside to be safe. Then we started developing apps.”

“In Albania, the emergency services and other authorities were not prepared for such an event,” said Shpati Jupe, managing director of GDi Tirana. It was an all-hands-on-deck moment, with agencies across Albania and experts from around the world pitching in.

Jupe and Olli got in contact with staff at the City of Durrës to see how they could be of service. The internet was still up and running, so with support from the Esri Disaster Response Program (DRP), the small team in Tirana used ArcGIS Online to develop seven critical apps that helped citizens, city staff, and other decision-makers find emergency facilities, record damages to buildings, and figure out which areas of town needed the most immediate attention.

“Our solutions were the first ones that were developed and sent, very quickly, to the staff managing the emergency,” said Olli.

In the hours, days, and weeks after the initial earthquake, as powerful and frequent aftershocks continued to rock the region, these location-based apps made all the difference.

Four Apps Help Get Response Effort Off the Ground

The first thing the City of Durrës needed was a map that showed all its emergency facilities.

“Albania’s emergency management capacity at the local level is extremely limited,” explained Andrej Lončarić, managing director of GDi in Croatia. “There was no public website that citizens could reach out to to get this information.”

City staff gave the team point data for its critical buildings, including hospitals, police and fire stations, and first aid centers. Straightaway, Jupe, Olli, and their colleague Enxhi Masha, GDi Tirana’s product and solutions implementation specialist, built a web app to help citizens and emergency responders locate these facilities and prioritize where to send the wounded.

Next, the team contacted one of their partners, European Space Imaging, based in Munich, Germany, to obtain very high-resolution imagery of Durrës taken early that morning. Using the Esri Story Maps Swipe and Spyglass app template, the team built another web app that let users swipe new imagery onto old imagery to see which buildings had collapsed.

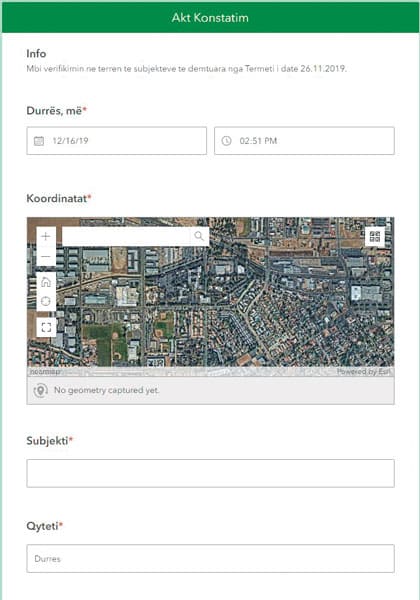

GDi Tirana also put together a Survey123 for ArcGIS form that citizens could use on their smartphones to quickly report damage to buildings. The idea was to get a broad overview of the devastation in Durrës and figure out where the worst damage was, so the form was simple. It asked respondents to record their name; phone number; the geolocation of the building they were reporting on; whether damage was low, medium, or high; any relevant photos; which village and/or administrative unit the building was in; and any additional relevant information.

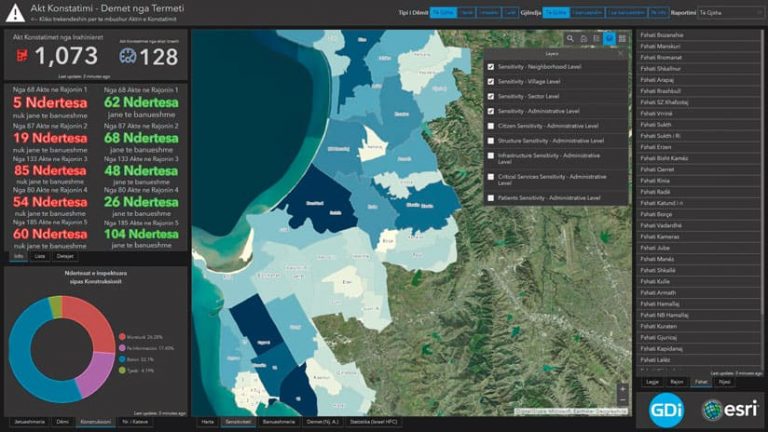

To ensure that authorities responding to the emergency could see what was happening on the ground and use that information to make decisions, Jupe, Olli, and Masha used ArcGIS Dashboards to build a real-time dashboard that consolidated all the data that citizens were recording with Survey123 into a map, charts, and graphs.

“We developed the dashboard together with the Municipality of Durrës. [Staff] told us what to change and what to add,” said Olli. “We made it available in both English and Albanian so it would be understandable by all the people involved.”

By 9:00 a.m. the morning of the earthquake, Jupe, Olli, and Masha delivered these three apps to the City of Durrës. Staff posted the critical facilities map and the Survey123 form on the city’s website so citizens could easily find them and made all the apps available to other responding authorities, including the City of Tirana, the ministries of defense and the interior, and the national civil protection agency. By noon, all four apps were in full use.

“It was very important to have tools like the ones that we built in the early hours, as the situation was unfolding, to help, in real time, with gathering quality information and creating quality tools,” said Jupe.

A More Detailed Way to Prioritize Needs and Resources

Over the next few days, GDi Tirana focused on refining the data being collected in the field and presenting a more detailed picture to authorities. This involved working not only with the City of Durrës but also with other specialists who descended on the region to help with response efforts.

One of the first groups that deployed to Albania following the earthquake was a team of engineers from the Israeli Home Front Command, the emergency response and civil protection branch of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). The engineers were tasked with helping Durrës and other communities survey buildings and classify their structural damage.

“They saw immediately that the City [of Durrës] was using the tools that we had built,” said Jupe. “They were happy about that because they also use the ArcGIS platform for their emergency management operations.”

“They introduced us to the concept of sensitivity, or pain, mapping,” said Olli. This is what the IDF uses to prioritize needs and resources. “It’s a combination of different types of data layered on top of one another, and each one is given a certain amount of weight, based on a calculation, which, at the end, provides a more complex overview of the situation,” explained Jupe. “You can combine these different types of data and, through mathematical formulas, better understand what’s going on in the field and prioritize what you need to do.”

Less than two weeks after the initial earthquake struck, on December 8 at 11:00 p.m., the GDi team met with engineers from the Israeli Home Front Command to learn more about the concept of pain mapping, which is part of a system that won the Home Front Command a Special Achievement in GIS (SAG) Award at the 2019 Esri User Conference. The idea was to split up immediate issues into five categories, define whether each need was high or low, and then combine everything to show which areas of Durrës had the highest sensitivity and needed the most immediate attention versus which areas could wait for assistance.

The five categories consisted of the following:

- Citizen sensitivity: The number of damage reports sent in by citizens divided by the total population of that area

- Structural sensitivity: The number of damaged buildings divided by the total number of buildings in an area

- Infrastructure sensitivity: How much of a piece of infrastructure was damaged divided by its total length

- Critical services sensitivity: How many facilities were damaged divided by the total number of facilities in that area

- Patient sensitivity: The number of people in a living unit, within a certain age range, that needed help divided by the total number of people in that unit

Olli and Masha worked all night to build the app and get it ready for use in the field.

“In the morning, we did some quick tweaks with the Israeli guys, and then the chief of the Israeli team showed the app to the prime minister and Albania’s emergency team directly in the field while they were inspecting some damaged buildings,” said Jupe.

The GDi Tirana team also built a second Survey123 app that city and national government staff members used to do further assessments on the damaged buildings that citizens reported. To present this new, more detailed survey data, the team developed another dashboard, in both Albanian and English, with some additional functionalities, including widgets, gauges, pie charts, and serial charts. Because the engineers from the Home Front Command were using Survey123 for their work, too, they fed their data directly into the dashboard as well. All this gave decision-makers the ability to quickly determine which buildings were livable and which ones weren’t, as well as which regions, villages, neighborhoods, and administrative units needed rapid assistance.

“This was a very efficient and fast way to respond to a disaster situation with the right tools and solutions to help staff in the field be precise, fast, and effective,” said Olli.

Next Time, Albania Will Be Prepared with GIS

Over the next few weeks, the citizen-reporting survey recorded more than 1,800 records, and its accompanying dashboard showed an average of 117 views per day. The second survey ended up with almost as many records, showing an average of 15 views per day.

“This emergency demonstrated all the benefits of having a cloud-based solution,” said Lončarić. “It showed how robust ArcGIS Online is, how well it can scale, and how secure it is.”

“After this very good cooperation, which the City of Durrës has valued so much, it looks like [it is] going to expand [its] GIS capabilities and use of Esri technology,” Jupe said. “Not only that, but the national government is now pushing for all cities, countrywide, to adopt GIS technologies for emergency management and other city operations, such as maintenance.”

“We are now talking to the Albanian government about getting funding from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) so they can equip themselves with the ArcGIS platform,” Lončarić added. “Next time something similar happens, they can be prepared to respond to it themselves—with our support, of course.”