GIS Hero

People understand how important the earth’s ecosystems are. Terrestrial, marine, and freshwater ecosystems give humans goods and services that are critical to our survival. Yet most people don’t know what these ecosystems really are or even where to locate them.

That is why Roger Sayre feels that his current project mapping global ecosystems—on land and in oceans and freshwater—at fine resolution is the most exciting and important work he has ever done.

“The concept for ecosystems has been around for a long time, and you have a lot of ecologists who study how ecosystems work,” said Sayre, senior scientist for ecosystems at the US Geological Survey (USGS) Land Change Science Program. “What we haven’t had,” he continued, “is this long tradition of the science of ecosystems geography—understanding what ecosystems are out there and where they’re located.”

Sayre received a commission from the United Nations (UN) Group on Earth Observations to lead this project. The goal is to bring the power of earth observation to a larger community by mapping all of the world’s ecosystems so that more people can use this to try to solve some of society’s most pressing problems.

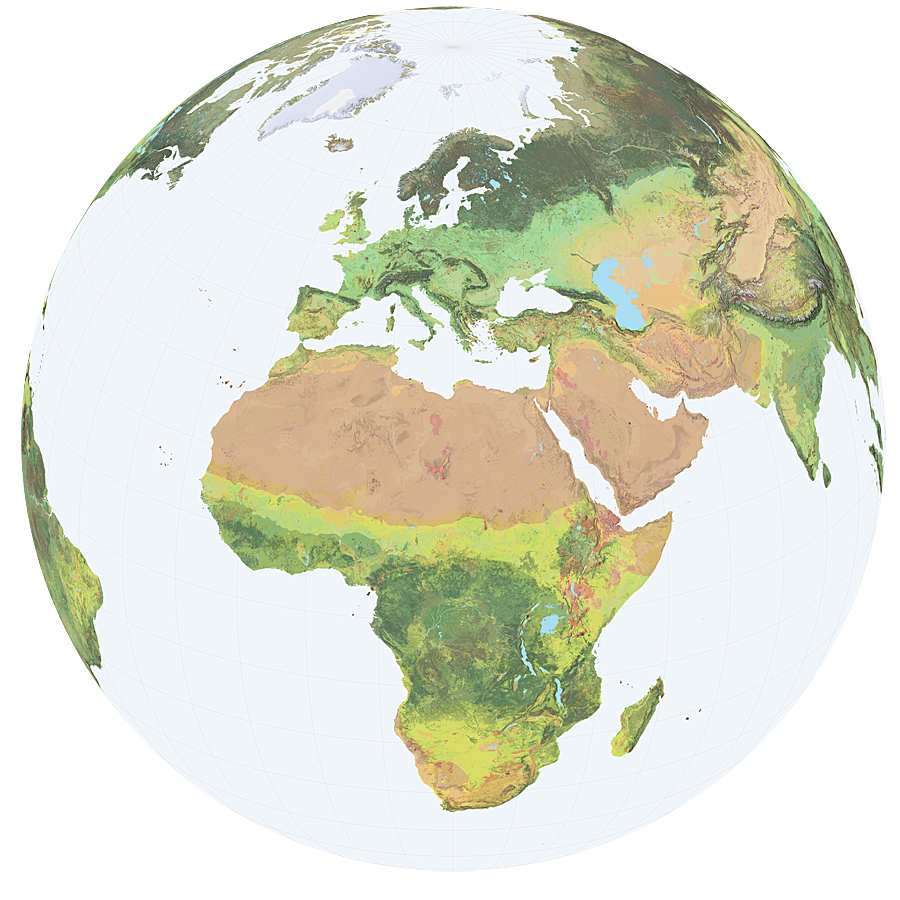

Sayre uses 250-meter resolution data—the finest spatial resolution available for this kind of map—to show geographic patterns and relationships at a level of detail that is useful to not only scientists but also land planners, resource managers, and conservationists. The final product almost looks like a satellite image, but it is built using datasets rather than sociopolitical boundaries or expert opinions.

Under the UN commission, Sayre began by making ecological maps of individual continents rather than of the whole globe. At the time, that was all he had the resources to do.

In 2013, he launched his ecological map of the African continent at the AfricaGIS Conference, where Esri founder Jack Dangermond was giving the keynote speech. The two had coffee, and Dangermond expressed how important he thought it was for the world to have a basemap of global ecosystems. Dangermond told Sayre he would help with putting together the global ecosystems maps, and within a year, a whole team was working on the project.

In December 2014, the USGS and Esri unveiled the Global Ecological Land Units (Global ELU) map. “I never expected it to go so quickly,” Sayre said of the Global ELU project, “but I never doubted that [it] would happen.”

Sayre has always been interested in maps and the natural world. His father was an avid backpacker and took him on backpacking trips every summer, where Sayre, who was intrigued even then by spatial relationships, learned to read topographical maps from the USGS.

He went on to study plant sciences at the University of California, Riverside. His then-girlfriend (and now, wife) convinced him to take a field botany class from Dr. Frank Vasek. Although he was reluctant to study “flowers,” as he recalled, Sayre now cites Vasek as a strong inspiration for his current mapping projects.

“That’s where I really started to think about the distribution of vegetation and ecosystems on the landscape,” said Sayre.

Vasek taught his students the history and geography of desert and coastal areas in Southern California, and that’s when Sayre realized what he wanted to do in life.

Before continuing his studies, Sayre spent four years in Africa with his wife. They went into the Peace Corps together in Swaziland, where he was a science teacher and she taught math. Sayre credits his time living in and traveling around Africa with shaping his views on open data.

“You just have to help people out and give them what they need,” he said, “and giving data is fundamentally important.”

When Sayre returned to the United States, he got a master’s degree in forestry from Pennsylvania State University and then a PhD in natural resources from Cornell University.

It was at Cornell, while he was doing research on acid rain, that he stumbled upon GIS for the first time at the Cornell Remote Sensing Lab.

“I saw some people on computers looking at maps,” he said. “They were digital.”

He thought that spatial analysis was indispensable, so he convinced his adviser to let him learn GIS. Using ARC/INFO, Sayre became skilled at doing spatial analysis with some of Esri’s earliest software.

As he neared the end of his PhD program, Sayre saw an advertisement for a GIS manager position at The Nature Conservancy for its Latin America and Caribbean science program. He got the job, and that was his real start in GIS.

Sayre was the organization’s first GIS manager. He soon moved up the ranks, becoming the manager of all information programs, then the director of science programs, and finally the director of The Nature Conservancy’s whole international conservation science program. This took him away from mapping for a while.

But in 2005, Sayre accepted a senior scientist position at the USGS, which got him back into mapping and GIS.

Now that the Global ELU map has been released, Sayre is working with Esri and a number of ocean scientists on the next phase of the UN-commissioned project: the Global Ecological Marine Units map.

The project, launched in February, is in the very early stages of development. It has complicated components, including having to map two 2D surfaces—the top of the water and the seafloor—and the 3D volume in between. But Sayre hopes that in a year, the group will have a really good understanding of marine ecosystems and perhaps even a draft map.

According to his colleagues, Sayre is the consummate scientist to have such an important role in all three ecological mapping projects.

“He is really interested in collaboration and moving the discussion forward on what’s going on,” said Esri director of product engineering Clint Brown, who has known Sayre for almost a decade. “I am awestruck by his ability to engage with people in such a positive way.”

Perhaps that comes from the enthusiasm Sayre has for what he does.

“Five o’clock comes, and I don’t want to go home,” Sayre said. “I’ve ended up being able to do that thing for which I really have a passion.”

What drives Sayre is the freedom to think big and work with like-minded, committed people to do something really important.

He even gets to see the payoffs when he goes backpacking with his own family. They make it out to California’s High Sierras when they can, where Sayre often finds himself wondering if he and his team have mapped things correctly.

“It looks like granite with conifer forest,” he finds himself thinking.

It seems that the work is never done when mapping all the world’s ecosystems.

Read other articles in the “GIS Heroes” series.