Think about the last time you tried to learn something new. Perhaps you wanted to hike to the top of a mountain or start using artificial intelligence (AI) tools at work. Did you climb to the peak on your very first hike? Did you outsource your entire job to AI within the first hour? Probably not.

You likely approached your learning goal via smaller, more familiar steps. You probably went for a 30-minute nature walk first and built up to your all-day ascent gradually, until you had the aha moment when you knew exactly how much water, food, and training you would need to make it to the top of the mountain. To learn about the latest AI tools, you likely started by reading articles and talking to colleagues about various AI platforms, got free trials for a few of them and poked around, and then had the aha moment when you realized which one would work for you. Only then did you begin implementing AI into select workflows.

When learning something new, it is helpful to start from a place of relative familiarity and break the learning process down into bite-size nuggets. This moves learners closer to that aha moment, when they recognize how their new knowledge can be applied to other contexts.

At the new Institute for Geospatial Education at the University of Massachusetts Global (UMass Global), that is how instructors educate students about geospatial technology. They meet students where they are—culturally, socially, and geographically—and hook into the knowledge and experience they already have before working to extend students’ understanding of the technology to new heights and realms.

Consider Culture

Culture, according to anthropologists Lara Braff and Katie Nelson, is “a set of beliefs, practices, and symbols that are learned and shared.” Culture is the lens through which people observe, discover, and act. Anytime groups of people come together, they bring their different cultures with them. So culture is important to consider when teaching people how to use geospatial tools.

Learning modules at UMass Global’s Institute for Geospatial Education actively regard students’ cultural and social norms and incorporate them into the learning process. The curriculum also includes real-world examples of how culture intersects with the use of geospatial tools in various contexts around the globe.

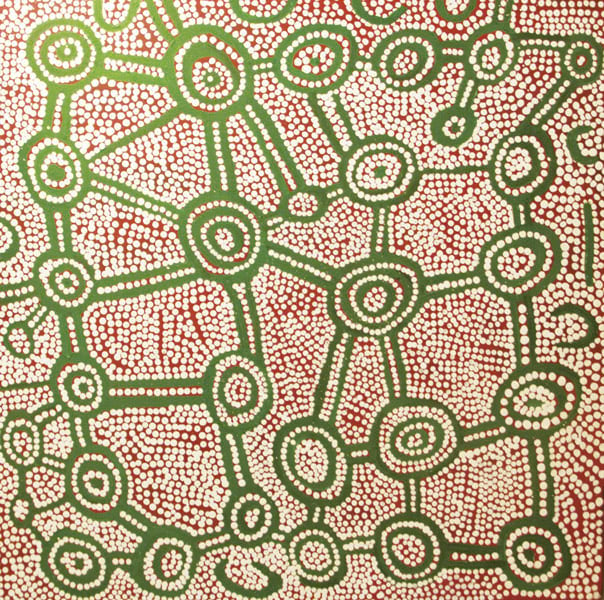

For instance, to help the Indigenous Martu people of Australia’s Western Desert manage their land and water systems in a modern context, GIS had to be implemented in a way that complemented the community’s cultural conceptions of space and place. As noted in Resilient Communities Across Geographies, edited by Dr. Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg and Steven Steinberg, the Martu’s traditional way of life centers on knowledge systems that are built around geography—and song and storytelling are key to keeping those knowledge systems intact. Thus, as researchers Sue Davenport and Peter Johnson discovered, GIS is best used in this context to preserve and enhance the cultural knowledge that the Martu already possess.

Teaching people how to learn new tools involves understanding different cultural patterns. This is true within any organization, school, or business. The way a particular group conceptualizes space and place is directly tied to what that group values and focuses on in the learning process. Members of the group orient themselves to the topic and interpret teachings based on cultural values and norms, as well as what is familiar in their own local cultures.

Bite-Size Nuggets

One of UMass Global’s goals is to provide people all over the world—many of whom have previously lacked access to education—with the opportunity to learn GIS in an applied environment. A big focus of that objective is to ensure that they are able to learn the technology through bite-size, culturally relevant nuggets.

To do this, UMass Global is collaborating with Esri to break learning down into specific ideas or facts—nuggets—that can be taught in a few minutes to an hour. Students can then take the key concepts that they learn and build toward earning microcredentials, certificates, and degrees. UMass Global incorporates ArcGIS technology, materials from Esri Academy, ArcGIS Blog posts, and more to teach students how to use GIS in ways that positively impact leadership, communication, strategic thinking, and decision-making.

Through conversations with interdisciplinary geospatial leaders, including members of the Institute for Geospatial Education’s advisory board, instructors have created a big-picture view of the geospatial skills that students need to acquire. These include not only technical experience but also soft skills that are critical to achieving success. Students stack learning units on top of one another to amplify their existing competencies and create a new line of knowledge within their disciplines. This helps learners discover how to use geospatial tools in business, for emergency management and economic development, in concert with other technology such as AI, and in a host of other situations.

UMass Global teaches the Geographic Approach, a methodology that encourages learners to ask location-based questions; acquire, examine, and analyze data; and act on the results. This method ensures that the goal of using geospatial technology is to encourage action, aid with problem-solving, and influence policymaking. Because what good is studying a technology or challenge if it doesn’t lead to progress?

As Esri director of product engineering and Institute for Geospatial Education advisory board member Clint Brown said about the program, “You rapidly become part of an ever expanding group of problem-solvers capable of addressing the big challenges that face our planet.”

Esri education manager Michael Gould, an affiliate of the institute, echoed that sentiment.

“Organizations are looking for more than people who know what GIS is,” he said. “They are looking for decision-makers who are capable of using geospatial thinking for problem-solving.”

The Aha Moment

Meeting students where they are acknowledges their lived experiences as well as their existing knowledge and skills. It creates a framework for engagement and provides learners with a launchpad for success, whatever their backgrounds may be.

Packaging instruction into bite-size nuggets increases the accessibility of education and improves learners’ confidence that they can achieve their goals. This is because of assimilation, a process wherein people integrate new learning with knowledge they already have. When students acquire new skills by participating in authentic problem-solving via a culturally familiar frame of reference, they are more likely to retain that knowledge and apply it in novel contexts.

Teaching GIS this way crosses global geographies. As students acquire more skills, the problems they are asked to solve become more complex and occur in different environments. And along the way, they receive recognition—in the form of microcredentials—of their growing skill sets. This motivates students to keep learning and ties credentials to competencies, which gives employers confidence that potential employees do indeed have the skills they claim to have.

Many people around the world can learn how to use GIS by first applying the technology in small ways to issues that they already understand. Once they achieve that aha moment, they can take their skills and start on the path to tackling more complex problems.