At the 39th Annual Esri User Conference, held in San Diego, California, July 8–12, more than 18,000 attendees learned about new geospatial technology, networked with colleagues from around the world, and shared how they use GIS to foster data-driven change.

The theme of this year’s conference was GIS: The Intelligent Nervous System, a metaphor built around the human nervous system, as Esri president Jack Dangermond explained.

“The human nervous system…is intelligent,” he said. “It integrates data from many sources [and] couples that data with logic and reasoning; ethics; values; and in some cases, emotions. And then it carries out coordinated responses.”

Sound familiar?

Likening the earth to a living organism, Dangermond said that we need something like the human nervous system to create a more sustainable future. We fundamentally need more understanding and collaboration, which GIS is very good at enabling.

“It starts with geography, the science of our world,” he said. “Geography helps us see complexities and relationships and patterns. It helps us see holistically and respond more intelligently.”

Renowned biologist and Harvard University professor emeritus Edward O. Wilson pointed out that GIS is helping us see environmental problems clearly and work together to solve them. Jane Goodall, DBE, added that GIS helps us see hope in the face of enormous challenges, as she discussed during the keynote conversation she had with Wilson and Dangermond.

See What Others Can’t

At the conference, Esri introduced a new phrase—See What Others Can’t. Many user presentations were woven together in the Plenary Session.

Hearing from local governments, including the City of Pasadena; nonprofit organizations, such as the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD); private companies; federal agencies; transportation authorities; and even young students, attendees discovered all sorts of ways to use GIS to integrate data, find patterns, strengthen collaboration, and turn problems into solutions. Here are a few of those stories.

With Help from Residents, a City Sees the Effects of Climate Change

Like many places around the world, the Netherlands is threatened by climate change. Much of its land is below sea level, with 65 percent of it vulnerable to flooding. The low-lying city of Zwolle, with its rivers and canals, is exceptionally at risk.

“We need to be resilient to climate change, and GIS is helping us do that,” said Marcel Broekhaar, an adviser for the City of Zwolle’s Smart Zwolle initiative.

To be more proactive about flooding, the city traded its passive open data strategy for a more collaborative approach. In the neighborhood of Stadshagen, Broekhaar and his team wanted to involve residents in flood monitoring, so they created an ArcGIS Hub initiative called SensHagen. They built and dispatched weather and air quality sensors and then held a meeting for residents to show them how the sensors work and where to access the data on the hub.

“[Residents] appreciated that we involved them,” said Broekhaar. “They wanted to participate.”

And they did. Local university students made more sensors and installed them around Stadshagen. The city put on “hub evenings,” where residents learned how to use SensHagen Hub to make maps and analyze data. People downloaded a Survey123 for ArcGIS app to report standing water. A group of engineers even built wet feet sensors that report flooding directly to the hub—and now other residents are constructing and installing their own.

“Soon, we will have a system-built network of these sensors sending data to the hub,” said Broekhaar. That will enable the city to do concrete analysis on climate change by identifying heat islands and seeing which areas are prone to flooding.

“What started as a project became an initiative—and is now a movement,” added Broekhaar.

Read more about the City of Zwolle’s Smart Zwolle Hub.

The Census Bureau Gets Ready to See an Entire Population

In the United States, the federal government is constitutionally bound to conduct a census every 10 years, and the 2020 Census is just months away.

“Our goal is to count everyone once, only once, and in the right place,” said Deirdre Dalpiaz Bishop, chief of the Census Bureau’s geography division. “To ensure we get it right, we incorporated the use of GIS throughout our design.”

To verify that every state, county, city, tract, block, and address is accounted for, the Census Bureau used imagery. And for census takers who follow up with nonresponding households, they will use an enumeration app, built with ArcGIS Runtime, on iPhones.

“Our route optimizer leverages data from industry leaders, combined with census-specific criteria such as work availability, and calculates [an] optimized case assignment,” said IT specialist Anika Adams-Reefer. All completed cases will automatically sync to the Census Bureau’s servers, saving time, money, and paper.

To help tribal, state, and local governments prioritize census outreach efforts, the bureau is using a configured web app—the Response Outreach Area Mapper, or ROAM. With this, local leaders can see areas where high nonresponse rates are predicted and plan appropriate actions.

“We’re able to make quick, well-informed, and responsible data-driven decisions to help motivate people to respond,” concluded computer mapping specialist Suzanne McArdle.

Find out more about how the US Census Bureau is using geospatial technology for the 2020 Census.

GIS Provides New Ways of Seeing Threats to Protected Areas

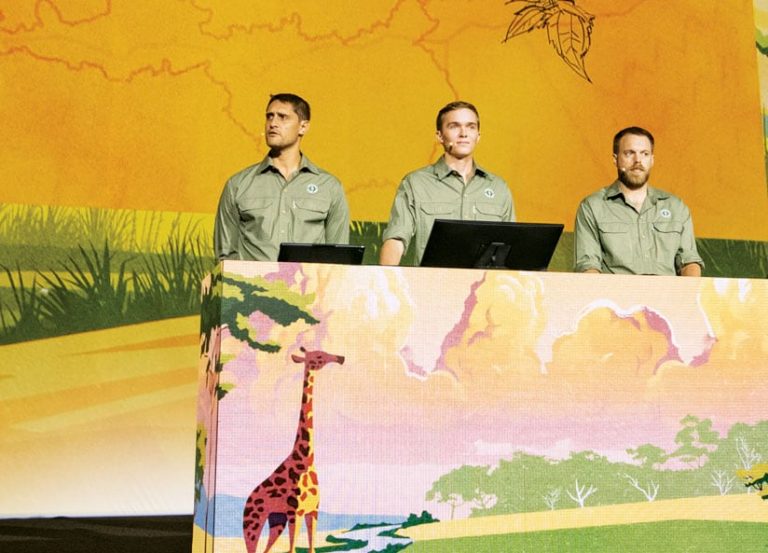

Across Africa, protected areas face increasing pressures, yet many national parks lack enough resources to engage in sustainable conservation and development. That’s where African Parks—a nonprofit organization that partners with governments and local communities to restore and manage protected areas—comes in. But it’s a big job that spans 15 parks in 9 countries.

“Working at this scale across Africa’s diverse landscape requires holistic and adaptable management,” said Geoff Clinning, African Parks’ technology development manager.

Using a vast network of sensors along with ArcGIS technology, including a unique configuration of ArcGIS Pro, African Parks combines traditional conservation measures with context-based strategies.

It fuses “our understanding of the human and ecological landscapes,” explained Naftali Honig, the organization’s director of research and development at Garamba National Park.

In Garamba, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the organization executes one of the most complex anti-poaching efforts in Africa. By monitoring collared animals, including elephants, the team can tap into their intelligence and see in real time, on a map, when a herd is acting erratic—perhaps to evade poachers.

“Visualizing [this] draws our attention to [that] area and drives us to understand the context and landscape around [those] particular animals,” explained Evan Trotzuk, African Parks’ cyberinfrastructure officer at Garamba.

African Parks also records other indicators, such as fires or illegal camps, and always knows where its rangers are so they can be dispatched directly to where poachers might be. This has helped reduce elephant poaching in Garamba by more than 90 percent.

The organization also uses GIS to work with surrounding communities. Outside of Rwanda’s Akagera National Park, African Parks started a fishing operation that generates revenue for the community while promoting sustainable fishing. And near Liwonde National Park in Malawi, the organization runs a beekeeping program to stimulate local honey production.

Treating these unique landscapes as a nervous system—complete with sensory inputs, related analyses, and intelligent actions—is a good start. However, there is still much to do to ensure that Africa’s protected areas thrive for generations.

Seeing At-Risk Biodiversity, and Planning Around It

NatureServe, a nonprofit that provides species-related data, tools, and services for conservation purposes, uses GIS to better see and understand where to find at-risk species in the United States, Canada, and Latin America. To help guide conservation efforts, it created the high-resolution Map of Biodiversity Importance for the United States—the first map of its kind.

“Using Microsoft cloud computing and Esri’s modern [GIS] tools, we are able to generate, analyze, and share biodiversity data at a pace and scale never before possible,” said Healy Hamilton, NatureServe’s chief scientist. “We’ve produced detailed maps of the geographic distribution of over 2,000 species at risk—plants and animals, vertebrates and invertebrates, both aquatic and terrestrial. We’ve stacked these maps to see what we’ve never seen before. We can identify the places that matter for sustaining our nation’s biodiversity.”

Florida, for example, has undergone rapid development, but it’s still rich in biodiversity, according to Hamilton. With NatureServe’s data models and new interactive mapping capabilities, governments, businesses, and organizations there can find out which species—and how many of them—are at risk. They can see, for instance, whether there are butterflies, crayfish, or salamanders near a proposed development and how imperiled they are.

“This map provides conservation intelligence for better, smarter decisions,” said Hamilton.

The data for the Map of Biodiversity Importance was collected over the last few decades by a network of 1,000 botanists and zoologists in NatureServe’s network. Regan Smyth, director of spatial analysis for NatureServe, explained that for areas on the map where little or no data has been collected, data science can fill in the gaps.

“With Esri technology and support from Microsoft’s AI for Earth program, we’ve built a spatial modeling infrastructure in the cloud that allows our scientists—from New York to Arizona—to work together to fill in these blank places on the map,” Smyth said. “We are doing it by building predictive information models for thousands of species.”

With GIS, Students See How to Overcome Religious Divides

For 30 years in Northern Ireland, Protestant unionists and Catholic nationalists clashed violently over whether to remain part of the United Kingdom or become a united Ireland. Although a peace agreement was reached in 1998, a small town called Lurgan is still divided along religious lines.

But there is hope. This year, students from two Protestant schools and one Catholic school participated in a citizen science project together in Lurgan. They visited 15 sites to “map how people felt at a variety of Protestant and Catholic areas in our town, both during the day and at 10 p.m. on a Saturday night,” explained Catholic school student Aiesha Mouhsine.

At each site, students used Survey123 for ArcGIS to record how comfortable or uncomfortable they felt. Back in class, they visualized their data on a map. They saw, for example, that Protestant students felt on edge while visiting a Catholic/nationalist monument but fine in a Catholic place of worship, and that all students felt comfortable at their schools.

“It was really quite exciting to see the patterns that started to emerge,” said Protestant school student Leon Van Der Westhuizen, who used ArcGIS Insights to analyze the data.

Local police and the town council are employing the students’ findings for further research, but data collection and exploration were only part of the project.

“It’s about breaking down barriers and building friendships,” said Hannah Trew, a Protestant school student. “We recognize that, yes, we are all different…but overall…there’s more that unites us than divides us.”