When Hurricane Helene struck the Carolinas on September 25, 2024, Dr. Patricia Carbajales-Dale and many of her colleagues at Clemson University—located about two hours from hard-hit Asheville, North Carolina—were stranded in their homes without electricity and internet. Yet, as so many communities came together to support one another after the hurricane, they found several ways to assist with relief efforts in and around Clemson, South Carolina—and even as far away as Asheville—using GIS.

“We all helped each other. We put everything else on hold, and we didn’t do anything but emergency response,” said Carbajales-Dale, the executive director of Clemson University’s Center for Geospatial Technologies. “I feel like with GIS, we have the tools and the power to help when things like this happen, so I should drop everything and help. Honestly, nothing feels more important or more meaningful to me.”

“You Know How Life Is”

Carbajales-Dale’s interest in GIS was ignited during a different kind of emergency when she was in college in Madrid, Spain. She was studying forestry and engineering, and there were massive forest fires around her hometown of Ourense, in Galicia.

“I saw that GIS could bring all these models together showing the slope and the wind direction and the vegetation and where the helicopters were,” she recalled. “My dad was an architectural drawer, so he used to do things by hand. And then CAD and AutoCAD came into his field, and it kind of took over. So when I was studying engineering and I saw GIS, I thought, ‘This is going to take over, so I better study it,’” she said.

Her university didn’t offer GIS classes, so she looked all over the world to find a master’s degree program in GIS. As she recalls, there were only three at the time, so she enrolled in the first cohort of GIS master’s students at the University of Redlands in California—a few miles away from Esri’s headquarters. She figured she’d stay for a year, get her degree, improve her English, and then take the technology back to Spain and apply it to forest fires.

“But you know how life is,” she said.

After graduating, Carbajales-Dale got a job at a water resources consulting company in Santa Barbara, California. She then worked at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the planning department before being hired by Stanford University, where she established and ran the Stanford Geospatial Center.

“It was a dream job” said Carbajales-Dale. “My job was to help people use GIS. I would get a surgeon who needed help with data for surgery patients, or I would get someone from urban studies. It was an incredible experience.”

While at Stanford, Carbajales-Dale developed and taught a course called GIS for Good that allowed students to work on projects for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (now known as UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency), the International Rescue Committee, and two other nonprofits. During the course, representatives from the agencies flew in from Geneva, Switzerland, and elsewhere to support the students. Carbajales-Dale also got a startup satellite company (that is now a well-known imagery provider) to direct its only satellite at some of the class’s projects so that the students could use imagery.

“It was just everybody coming together to make this class successful,” she said.

The students mapped refugee camps to help one organization determine where to put solar equipment. They helped another organization map its operations in several countries to figure out where to increase outreach efforts about its services. They also did a suitability analysis to help one organization choose where to put its support offices near a conflict-ridden international border.

Despite the time differences between the students and stakeholders and the complexity of the projects, “the students really responded well to the challenges,” Carbajales-Dale said.

She only got to teach the class once, however, because after just four years at Stanford, her husband—whom she met when he was a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford—received a faculty job offer at Clemson. So she moved with him, ready to continue innovating with GIS at a new institution.

Spotlighting Cool Tech While Focusing on Impact

Clemson is a land-grant university in western South Carolina that is deeply committed to not only supporting education and research but also providing public service and outreach to the local community, especially farmers.

“Clemson offers a geography curriculum, but not in the traditional way you would see it at some other universities,” said Mark Lecher, an Esri account manager for the education sector. “The university uses GIS to help out local municipalities, the county, and others. They aid in 911 dispatching, help the county develop long-range framework plans, and things like that. And Patricia has grown GIS at the university so that anything Clemson does to help the surrounding communities, there’s a good chance that GIS is involved.”

When Carbajales-Dale moved to Clemson, she joined the IT department as a facilitator for the university’s supercomputer, the Palmetto Cluster. She also began teaching a GIS workshop in the basement.

“After 10 months or so, there was more demand, and then there was momentum to create a center in partnership with the library,” Carbajales-Dale recalled. “Now, in addition to me, we have the GIS manager, a GIS and drone specialist, a developer, a temporary GIS analyst, and an intern.”

She also renovated some space in the library, giving the Center for Geospatial Technologies a training room, a collaborative area, a sandbox, and even virtual reality equipment.

“Patricia is finding ways to get multiple departments, many people, and a ton of students really excited about GIS by spotlighting the cool things,” Lecher said. “And then she ties it back to the really impactful things that GIS can do.”

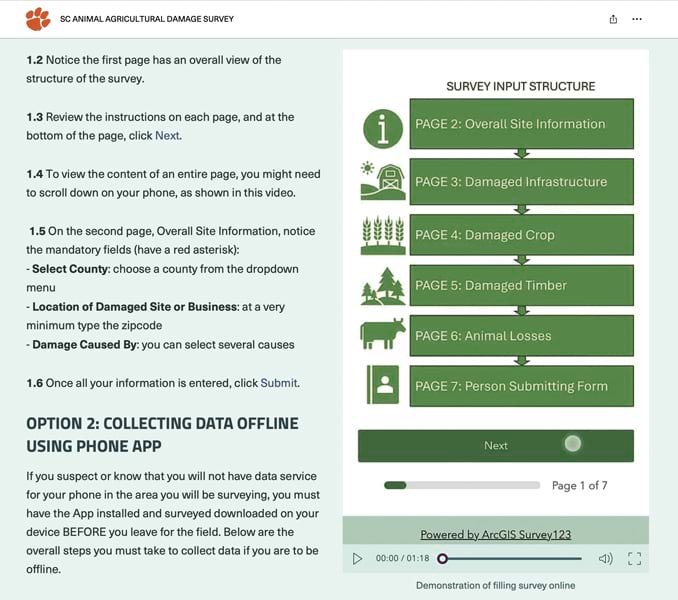

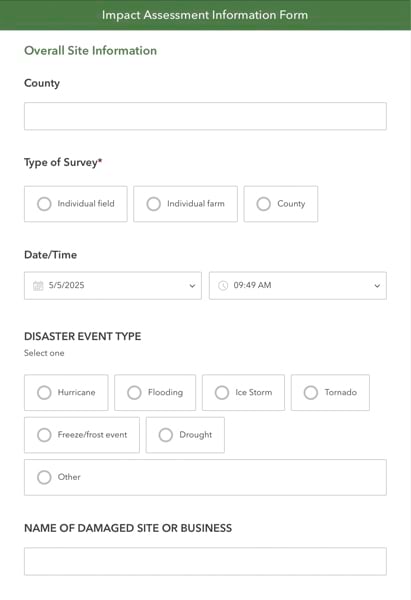

For example, when Hurricane Debby struck the southeastern United States in early August 2024, Carbajales-Dale and her team—in collaboration with Clemson’s Agribusiness Program—turned to ArcGIS Survey123. They employed Survey123 to develop a form that farmers and Clemson extension agents (university representatives who bring applied research to local communities and farms through educational programming and consultations) used to record information including how many acres got flooded, what farms’ estimated crop yield and loss was, and how much livestock was lost. They could include photos as well. This data was then reported to the county and, if needed, state and federal relief agencies to help facilitate disaster aid. The survey can be used for hurricanes, floods, drought, hailstorms, and any other natural hazards that affect agriculture.

The form used for Debby was too long, though, so Carbajales-Dale and her team began developing version 2.0. And then Hurricane Helene hit.

“We kicked it into high gear,” she recalled.

The Power of GIS During Emergencies

Hurricane Helene pounded Clemson, though not as hard as some other places. But since the area was not in the hurricane’s direct path, people were not very well prepared, according to Carbajales-Dale.

“In my neighborhood, we got trapped for two days. I couldn’t leave because we had trees that came down in the neighborhood,” she said. “I didn’t have extra food, and we lost electricity.”

Once her neighbors used a chainsaw to cut a path through the trees, Carbajales-Dale was able to get to Clemson to check on her team members and get to work.

At Pickens County, where Clemson is located, the GIS team was short two people, so Carbajales-Dale sent her GIS manager, Gakumin Kato, to work there. The county was also keeping track of anyone who called in or passed through the emergency center for help—to get oxygen or medicine, have a tree removed from their rooftop, or find shelter. Each evening, after Carbajales-Dale had worked all day and started working on wrapping up her PhD at night, Pickens County and two other counties sent her the data they’d collected from residents in need that day. She geocoded it, published it to ArcGIS Online, and sent it back to the counties.

Carbajales-Dale was in contact with the Esri Disaster Response Program (DRP) and Clemson’s Esri account manager throughout all this. They alerted her to an AI-based plug-in for Survey123 that was in beta that the counties could have used to automatically capture and geocode contact information from photos of residents’ driver’s licenses. Although Carbajales-Dale and her team got the plug-in working, the counties were too overwhelmed to switch workflows partway through the emergency. Carbajales-Dale hopes they can use it for the next emergency.

The Survey123 form that station agents had been using to help farmers after Hurricane Debby came in handy again—and it made a splash at the state and federal levels as well. Version 2.0 was shorter than the initial version, and station agents helped farmers across the region record damage. Newspapers reported the data, counties posted it on their websites, and even the South Carolina Office of Resilience asked Carbajales-Dale for the information.

“All this data then went to the governor and even to Washington, DC, to help farmers get aid for the losses they [sustained],” said Carbajales-Dale, who credited Dr. Adam Kantrovich, Clemson’s Agribusiness Program team director, with designing the survey form and summarizing the data for government officials.

These officials also used the data to run models that estimated additional relief needs, since not all farms filled out the form.

“Survey123 was a game changer for this because, before, this information came in on paper,” Carbajales-Dale explained. “Since Hurricane Helene, we’ve done another review of the survey, and we’ve trained about 80 station agents to use it across all sorts of disasters. It’s very important for the state.”

Another important project that the Center for Geospatial Technologies spearheaded after Helene was an analysis to help helicopter pilots figure out where to land to drop off aid. The ground was unstable, and some critical supplies had already been lost. Working in concert with a Clemson soils and avalanche expert, Carbajales-Dale’s team and Greg Dobson of the University of North Carolina, Asheville—who was working in the center while his hard-hit university was closed—put together models to determine the best places to land.

One missing piece of the project was satellite imagery, so Carbajales-Dale and Dobson asked everyone they knew to send any new imagery they could find of Asheville and the surrounding areas. Lecher, people affiliated with the Esri DRP, and even a friend from Carbajales-Dale’s master’s degree program who now works for the US Army Corps of Engineers delivered.

“It was a group effort,” Carbajales-Dale said. “Esri and Mark were reaching out, saying, ‘Patricia, there’s imagery from here.’ The Army Corps was telling me, ‘There’s this imagery.’ Everyone was pitching in. It was so beautiful to see how everybody was working together.”

Throughout her career, not only has Carbajales-Dale seen the power of GIS to bring people and information together, but also she has been a key driver of those faculties—as evidenced by her incredible, quick work in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene.

“GIS is so powerful, especially during an emergency,” she said. “It’s how we can truly make a difference.”