On Memorial Day weekend in 2015, a 40-foot wall of water rushed down the Blanco River and hit the city of Wimberley, Texas. The flash flood, caused by a freak rainstorm, destroyed major highway bridges and many vehicles and swept away a nearby vacation home and the eight members of a family inside it.

The ensuing search-and-rescue effort to find the family involved more than 1,500 volunteers and covered almost 100 miles of the river over several weeks. Fortunately for the responders organizing these efforts, Devon Humphrey lives nearby in Dripping Springs. The founder of Esri partner Waypoint Mapping, Humphrey has decades of experience in the use of GIS and emerging technologies, including unmanned aerial systems (UAS), for disaster response.

Mobilizing Assistance

Almost immediately after he heard that the victims’ friends, family members, and local community members had formed a volunteer force, Humphrey contacted Esri and began setting up geospatial tools that could be used in the search effort. Initially, Esri and Waypoint offered resources through the Esri Disaster Response Program, which offers free geospatial help during emergencies.

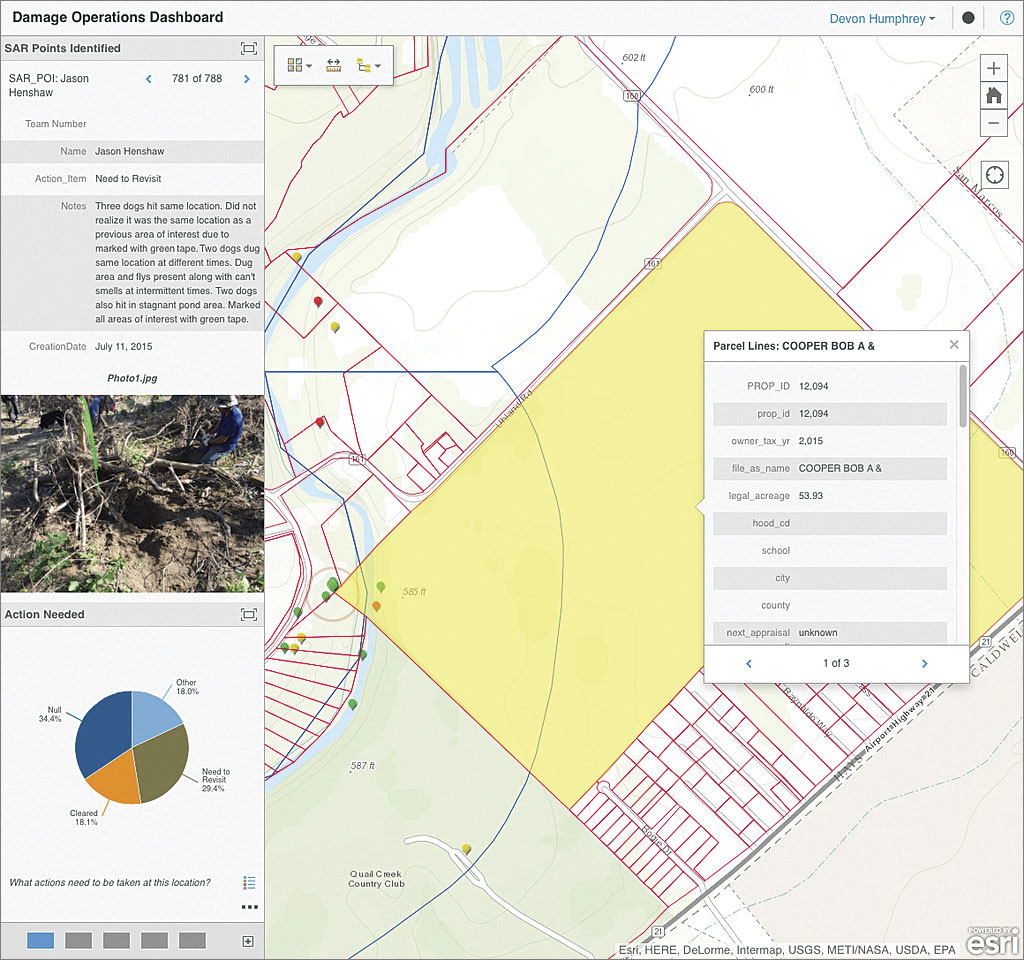

That help consisted of a property ownership map, real-time weather layers, and a data collection app that would feed a GIS dashboard for coordinating the search. This would enable those stationed at the volunteer command post (VCP) to coordinate rescue teams and view the resources assigned to the response. The data collection app was based on the Collector for ArcGIS app. The dashboard app was based on Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS. All data was hosted in Esri’s cloud-based platform ArcGIS Online.

Coordinating Volunteers

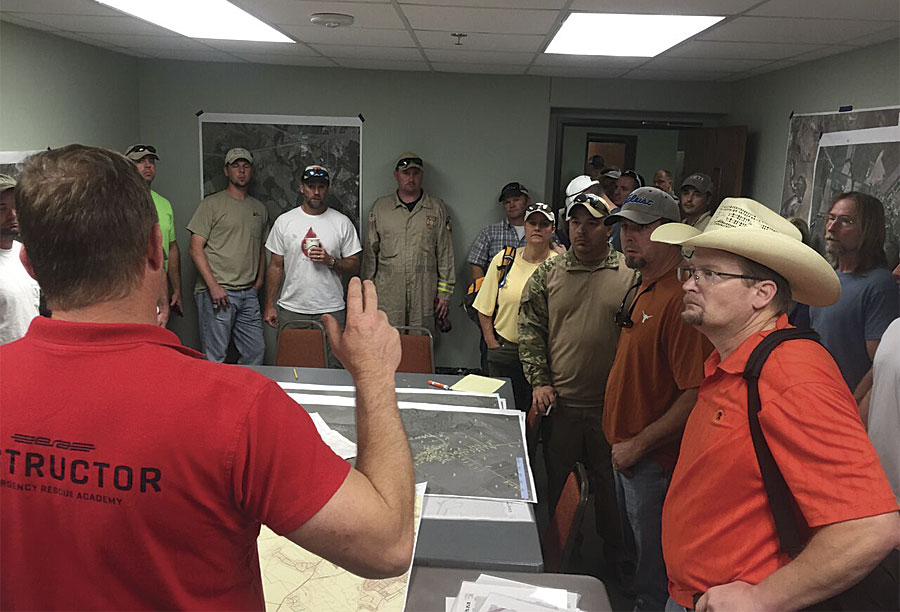

When volunteers and first responders convened on the morning after the flood, Humphrey was taken aback. The number of search-and-rescue (SAR) teams, each containing 8 to 12 members, had grown from an initial 25 to a staggering 125. Managing this many teams could be overwhelming.

Fortunately, nearly every volunteer owned a smartphone. Humphrey’s wife, Bonnie, who is not a GIS user, was able to quickly set up additional ArcGIS Online user accounts. Members of the additional 100 teams signed into ArcGIS Online and downloaded the Collector for ArcGIS app. Bonnie provided them with instruction on how to use the data collection app to post search data. Average training time for each volunteer team was about two minutes. All the volunteers understood how the app worked with the live dashboard and could see other search team members’ points of interest and the areas already searched appear in real time.

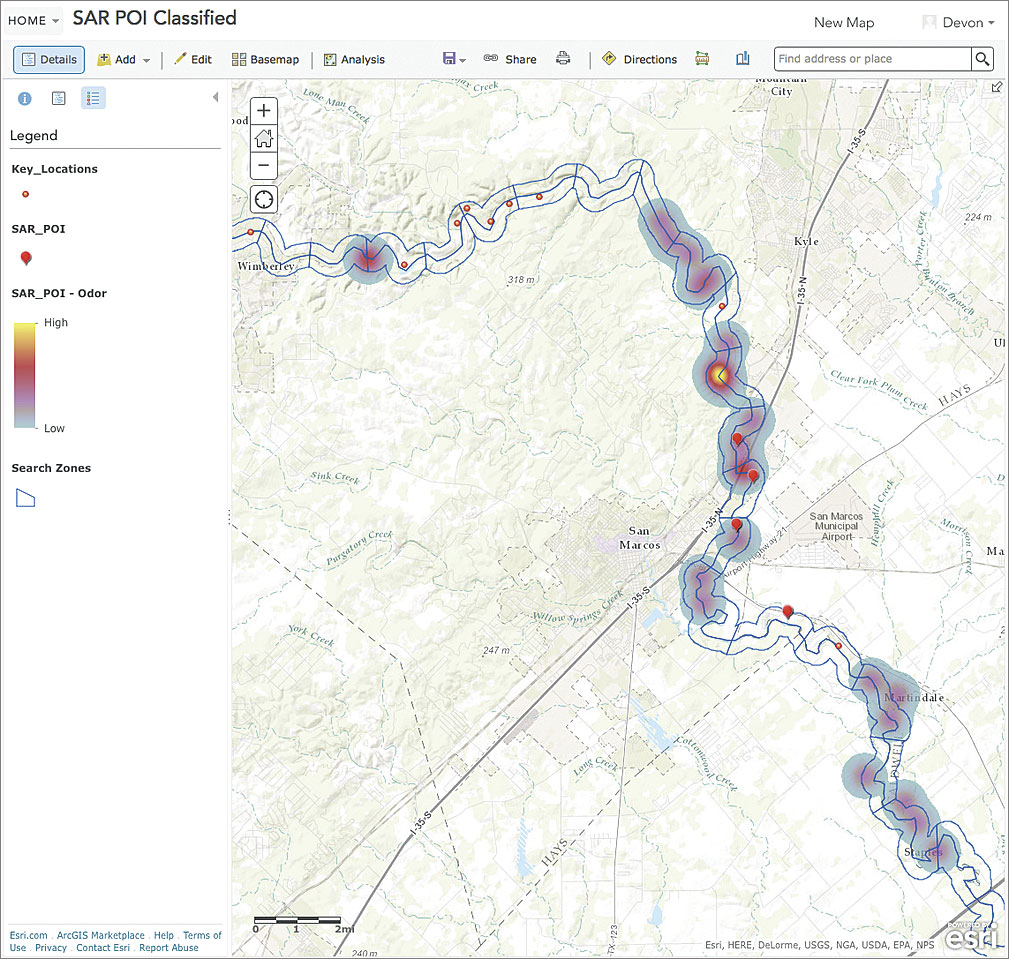

Within two days, SAR teams had collected more than 750 GPS data points, notes, and photographs. The points were color coded, and pop-ups on the dashboard displayed photos of additional information. Dozens of K-9 search teams, 17 manned helicopters, and other resources were dispatched based on information logged by the teams. “When I reported back to the Esri Disaster Response Program the amount of data that had been collected by non-GIS volunteers in such a short time, they were amazed,” said Humphrey.

Getting the Big Picture

The fire department suspected that a section of the river near Wimberley might contain a concentration of victims, debris, and cars that could be leaking fuel and other toxic fluids into the river. A few days into the response, they asked Waypoint Mapping’s sister company, Flightline Geographics, to use its UAS capabilities to capture new high-definition imagery of that area.

Since severe storms were ongoing and the river channel was still hazardous to navigate, a UAS was the safest way to capture this data in a GIS-ready format. Not only is a UAS capable of capturing higher-resolution imagery than a manned flight, but the rapid turnaround time would greatly help response. However, use of a UAS or drone required special clearance from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the federal agency that regulates the use of UAS.

Someone would also be required to act as the air boss, who would coordinate all UAS operations with the manned helicopters that continued to search the same area. Local Wimberley UAS expert and private pilot Gene Robinson served as the air boss. In that role, Robinson requested Beyond-Line-of-Sight (BLOS) permission for the UAS flights. Internationally known for search-and-rescue work, Robinson worked with Humphrey for several years on UAS projects for federal government and university research on wildfires and other topics. The FAA’s only condition was that visual observers (VOs) would be stationed along the route to maintain visual contact with the UAS and constant radio contact with Robinson. The city of Austin Fire Department Red Team provided ground support and VOs for the mission.

“This emergency clearance, including [the] BLOS [permission], was unprecedented,” said Humphrey. “Over the past five years, we’ve requested clearance from the FAA to use UAS for other major disaster responses, including wildfires and oil spills, but have never received permission until now. BLOS operations were instrumental because the river channel snaked back and forth and had steep canyon walls and high bluffs that made keeping the UAS in sight virtually impossible. By allowing BLOS operations, it allowed us to cover much more area, all in a single day.”

Vital and Timely Missions

On Saturday, Robinson and Humphrey then launched fixed-wing drones into the sky to capture imagery of the river channel disaster scene. Eight miles of the river were captured in high-definition 3D at 1.5-inch resolution. By Sunday, the raw imagery was GIS-ready and made available via ArcGIS Online image service to both GIS desktop and mobile SAR users in the field. The UAS image service was also shared with the Texas State Operations Center in Austin, which was activated for the disaster.

A web-based Esri Story Map Swipe app was used to show before and after imagery of the area. After images showed submerged vehicles, damaged infrastructure, and large debris piles that would require investigation prior to their removal. The clarity and rapid turnaround time of GIS-ready imagery was only possible through the safe and proper use of UAS. The data from those missions has since been used to verify proposed Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) floodplain revisions, an unanticipated but valuable application of the technology.

A Model to Follow

Although searchers ultimately recovered six of the eight victims, two children remain missing. The operation was so successful in terms of speed, accuracy, and deployment that Humphrey will use it as a model for future urgent missions requiring UAS intelligence. Using GIS and UAS to create a common operating picture helped SAR teams coordinate efforts and collaborate in real time without any special equipment—just smartphones and access to ArcGIS Online.