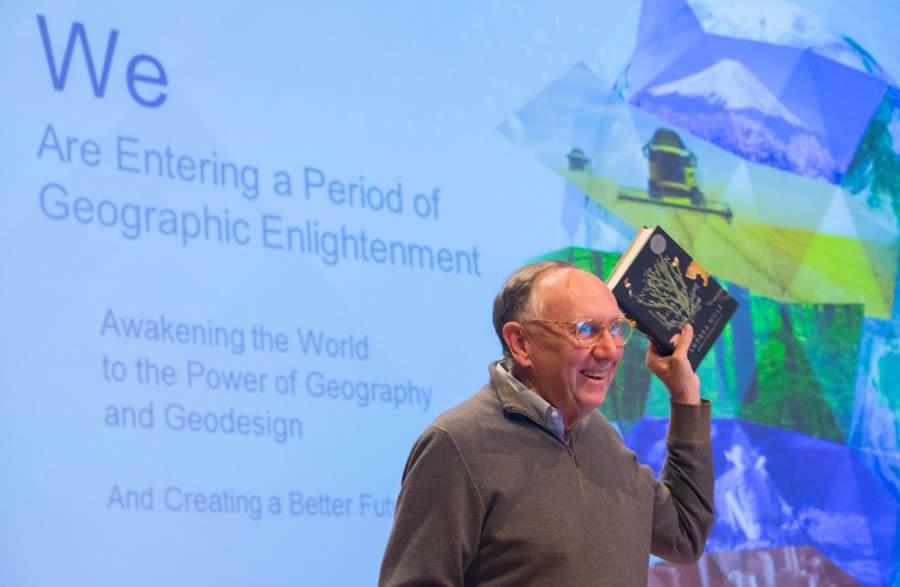

Esri president Jack Dangermond opened the 2016 Geodesign Summit with a book review of The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World.

“It’s a great plot,” he said, holding up a copy of Andrea Wulf’s biography of Humboldt, a German naturalist and geographer whose geographic explorations and scientific observations 200 years ago still impact how people think about nature today: as an interconnected, complex system.

If Humboldt were alive today, he might well have been at the forefront of geodesign, which supports designing with nature in mind and promotes a harmonious ecosystem. Geodesign couples geography with design. More specifically, it combines geographic science such as GIS technology, including the ArcGIS platform from Esri, with design methodologies to produce data-driven solutions or plans that support healthier, smarter, and more sustainable communities.

At the Geodesign Summit, Dangermond set the context for the event, outlining some of the issues society faces on a global scale. He spoke to the 300 people who met for the summit held January 27–28, 2016, in Redlands, California.

“You and I are living in a world that’s changing rapidly,” he said. “We are challenged [by] our population growth. And the footprint of that—and its impact on nature, on climate change, and on just about everything—is enormous.”

He called on the audience members to learn geodesign methodologies and supporting technologies in order to make positive changes in the years ahead. “It’s why we are so passionate about trying to create a better future, considering science and our best design and technology,” Dangermond said. “The world needs you. The world needs you to be inspired to grasp this whole set of methodologies and tools to work desperately to alter the course of what’s going on, because the arrows are going in the wrong direction by any measure. The challenge for geodesigners is to turn those arrows around.”

Greening of the Infrastructure

One geodesigner who is making strides in the right direction is the Spanish landscape architect, architect, and urban planner Arancha Muñoz-Criado. In introducing her to the audience, Dangermond described her as “one of the greatest geodesigners I’ve ever met.”

Muñoz-Criado has devoted much of her career to introducing land conservation and green infrastructure into the planning process in the Valencia region of Spain, where she grew up.

She loves the land, especially the bucolic fishing village on the Mediterranean Sea just south of Valencia where, as a child, she spent weekends and holidays. The people living there were poor, eking out a living by fishing, but their surroundings were rich and bursting with nature. “I grew up in a beautiful area in Spain with pristine beaches, mountains [overlooking] the seas, and wonderful terraces full of almond trees and vineyards,” Muñoz-Criado said.

But in the 1960s and 1970s, tourists from other parts of Europe discovered the fishing village and beaches. Soon a crop of summer houses replaced many of the almond trees.

“Suddenly, [the village] grew very, very rapidly,” said Muñoz-Criado. “It brought a lot of money and resources for the local people, so everybody was happy. But development was allowed anywhere, and that was a total disaster.”

Seeing what happened in her beloved fishing village influenced Muñoz-Criado in her choice of career. “I thought there was another way of growing—we could grow but grow well, preserving the character and preserving the landscape of the place,” she said.

After earning a degree in architecture in Spain, where she also was trained as an urban planner, Muñoz-Criado worked briefly for renowned Finnish architect Aarno Ruusuvuori. Sensing her interest in landscape design, he encouraged her to study landscape architecture in the United States.

Muñoz-Criado was accepted at Harvard University, where she earned her master of landscape architecture (MLA) degree in the early 1990s. She was a student of professor Carl Steinitz, the author of A Framework for Geodesign: Changing Geography by Design.

While in Boston with friends, Muñoz-Criado visited the Emerald Necklace, a seven-mile-long system of parks and waterways designed in the 1870s by American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Muñoz-Criado said the concept of green infrastructure can be traced back to him.

“Every time I went there, I said, ‘What a simple idea,'” Muñoz-Criado recalled. “Find out which places that you [want] to preserve before growing, and then develop around these places.”

She brought those ideas home to Spain but realized that, to achieve policy changes, she would have to take a role in government in order to help enact them.

She spent five years working for the government of the autonomous region of Valencia, advocating landscape conservation and green infrastructure requirements in the planning process. Moving up the ranks to eventually become regional secretary of territorial, urban planning, landscape, and environment, she eventually got the requirements put in place, thanks in part to the European Landscape Convention. The convention, adopted by the Council of Europe, seeks to create sustainable development based on balancing social, economic development, and environmental needs.

Muñoz-Criado also helped to get a European Union Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) for the autonomous region of Valencia. The SEA requires by law that Valencia take sustainability into account when reviewing development projects.

A Vision Coming to Fruition

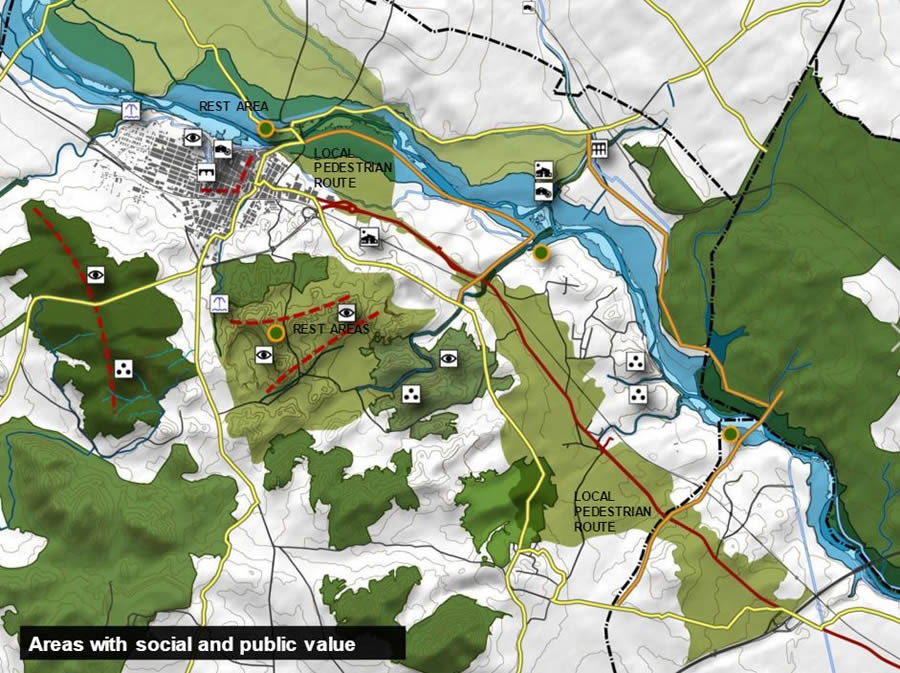

Today, the 550 municipalities in the region must use geodesign in the planning process and incorporate green infrastructure into urban planning. Those plans must be approved by the regional government.

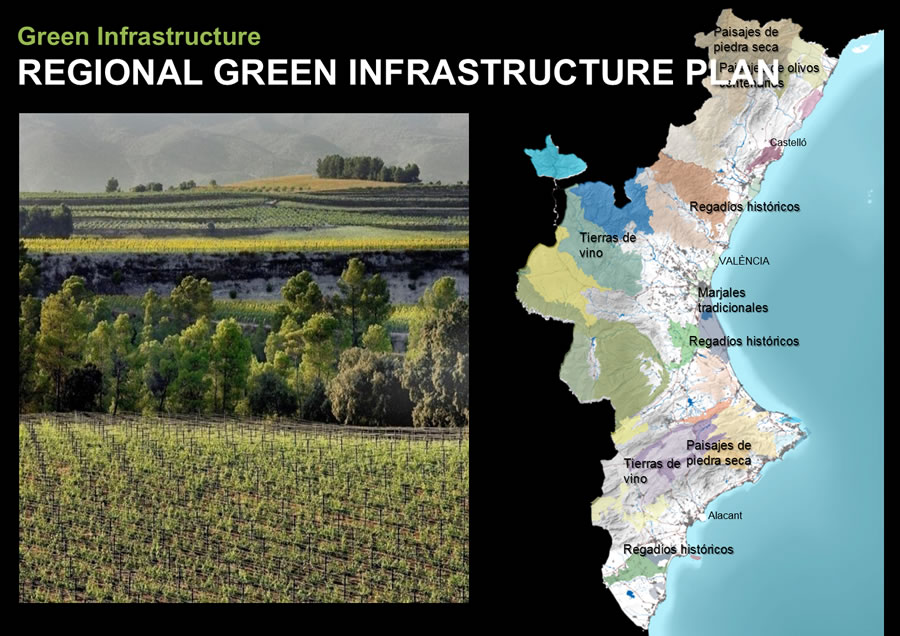

In the Valencia region, urban planning at both the regional and municipal scales incorporates green infrastructure. Working with others in regional government, Muñoz-Criado designed a regional green infrastructure map and a GIS application. Ecological, cultural, agricultural, and flood areas are shown on the map.

“Municipal planners, investors, and [other stakeholders] know that in the green areas, they have some environmental restrictions,” she said. “And they just have to click on the GIS map to know where they are.”

Today, a plan is in place to create a green infrastructure network in the Valencia region that promotes clean air and biodiversity. Rules set at a regional scale protect forests, wetlands, and agricultural areas. Huertas, or family gardens, are encouraged. In these gardens, landowners grow vegetables, such as tomatoes and onions, and then sell them at local farmers’ markets. Also, land is being set aside for bike paths, pedestrian walkways, urban gardens, green spaces, and urban parks. Views considered scenic or historic are protected too.

“If you have a beautiful mountain, you should not build anything that blocks the views of that mountain,” Muñoz-Criado said. “That mountain is part of the identity of that place and makes that place different from other places.”

Muñoz-Criado strongly believes that creating green infrastructure not only doesn’t run counter to economic development but actually enhances it. “Many cities have destroyed prime agricultural lands, but those lands can be the [food] markets for our cities,” she said.

Protecting prime agricultural land provides an economic boost for local farmers and saves energy and money by reducing the need for having food shipped from distant places. More people in cities can then buy locally grown fruits and vegetables. And tourism is stimulated where there are protected views of scenic areas such as the mountains and historic sites like castles. Recreation opportunities increase when hiking trails are built within green corridors.

“Everyone has different sensitivities, but I have always been very emotional about the landscape,” said Muñoz-Criado, whose home in the fishing village was only five meters from the sea. “I love being in beautiful landscapes. I have appreciated them since I was a child.”

Geodesign around the World

Muñoz-Criado was one of more than 30 speakers who took to the Geodesign Summit stage over the course of two days to talk about how their organizations use geodesign principles and tools in their work. For example, Paul Niedzwiecki, executive director of the Cape Cod Commission, spoke about how his agency helped to craft a regional water quality management plan using geodesign. Jie He, from the School Architecture at Tianjin University in China, talked about how geodesign is being used to study where recreational routes for hiking, bicycling, and other activities could be established around Yangze Village, in northern Fujian Province.

Attendees enjoyed the variety of topics that were discussed. Jane Tsong, a conservation planner who recently earned an MLA degree from Cal Poly Pomona, said she attends the Geodesign Summit every year for inspiration. She enjoys this summit in particular because the presenters focus on practical and evidence-based solutions to the big questions that communities around the world are grappling with, rather than emphasizing the nuts and bolts of software use.

“The variety of perspectives presented—from economic development in inner cities to watershed management and biodiversity conservation throughout Africa, Asia, South America, and the United States—inspires us to approach the issues with compassion,” Tsong said. “This is a spa for my mind and heart.”