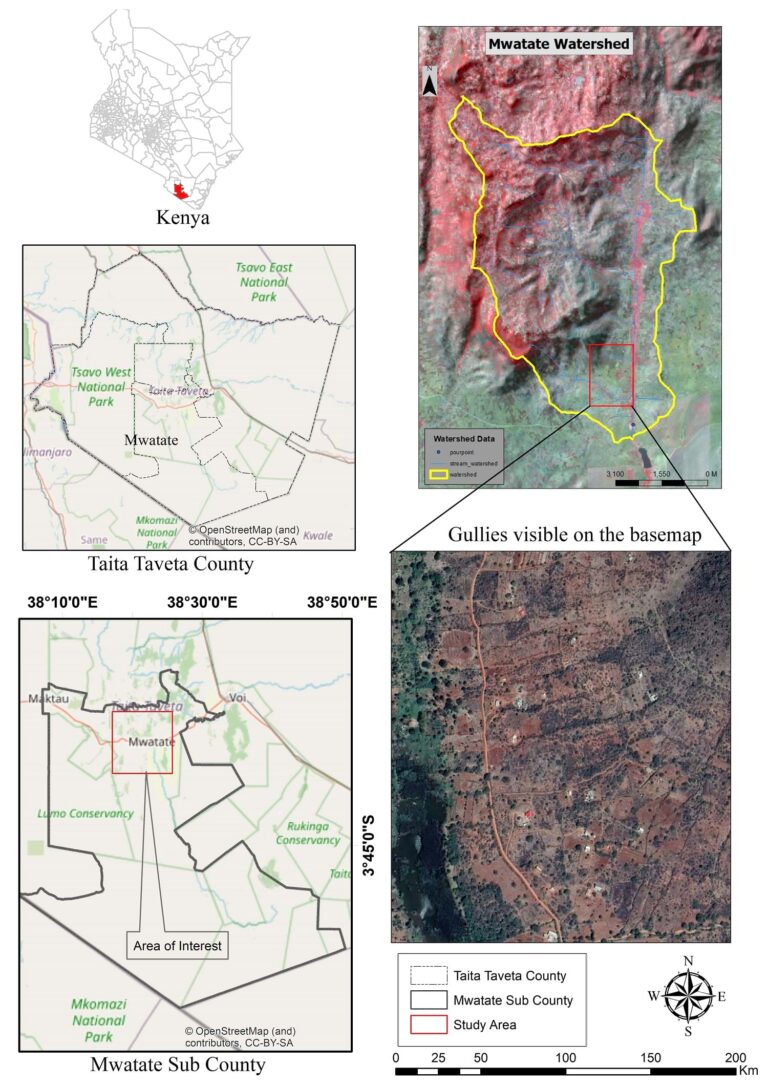

The economy of the Mwatate Watershed in southeast Kenya depends on mining operations, sisal plantations, and small-scale farming. However, these activities are becoming increasingly unsustainable due to of their significant impact on the land. Gully erosion—which occurs when surface water runoff removes soil along drainage lines—is a major problem in the watershed, and though accelerated by climate change, poor land stewardship has contributed most to its degradation.

“As a consequence of recent overgrazing, mining activities, farming, and deforestation, gully erosion in the Mwatate Watershed has become rampant,” said Francis Gitau, researcher and GIS/remote sensing technologist in the School of Science and Informatics at Taita Taveta University.

According to Gitau, these gullies are an acute problem in Kenya, exacerbated by the dumping of municipal waste that collects downstream. Leading to high sediment accumulation, the removal of fertile soil, and destabilization of hill slopes, gully erosion can cause an uptick in landslides, endangering life and property. Moreover, the loss of valuable productive topsoil reduces food production, contributing to food insecurity.

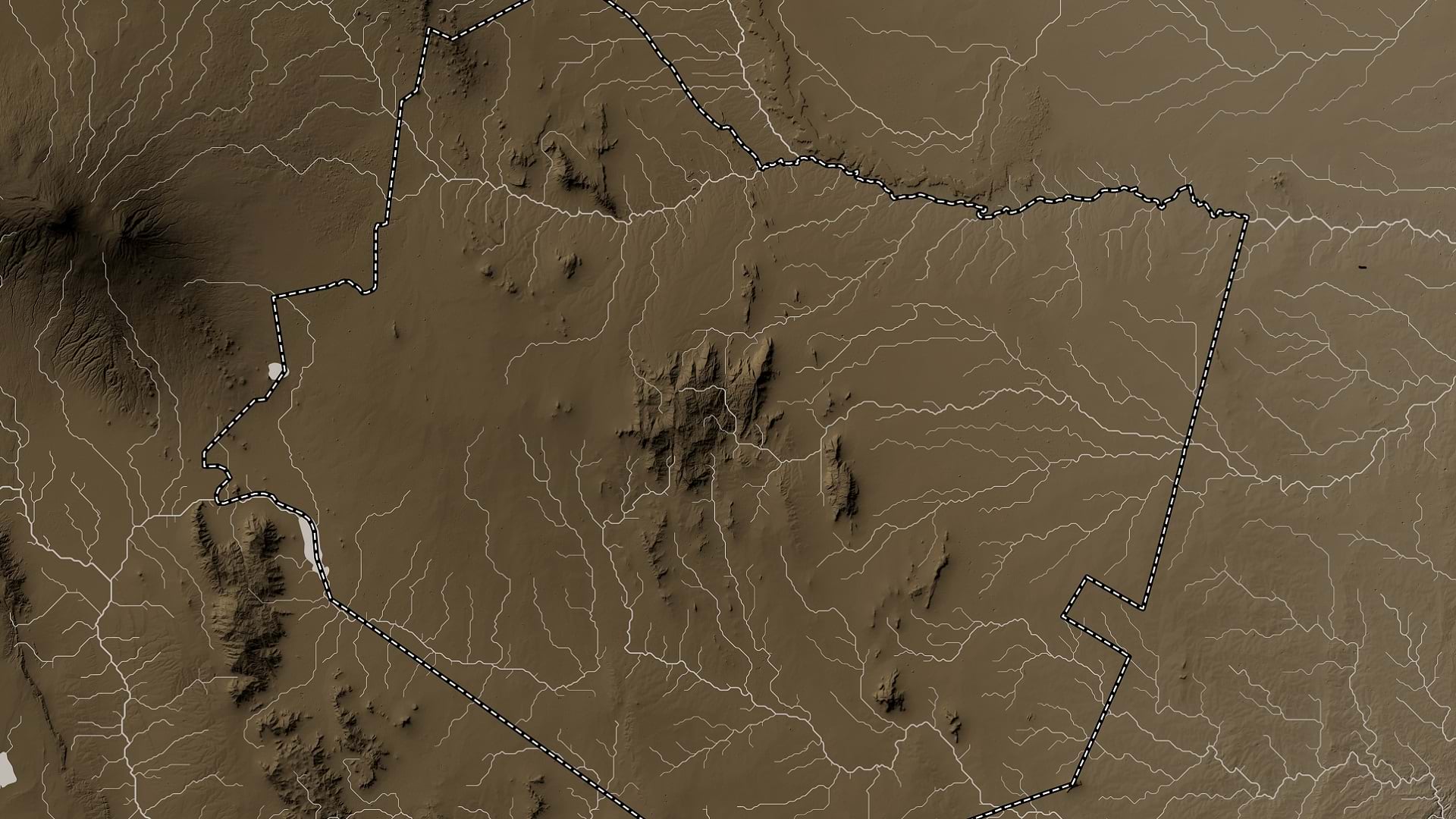

Gitau knows all too well that monitoring the progression of gully erosion is critical to mitigating its devastating effects. Therefore, he and his team at Taita Taveta University initiated a plan, beginning in 2020, to map the Mwatate Watershed to the basin or catchment level. With the help of software such as ArcGIS Online, ArcGIS Pro, and ArcGIS Survey123, the team has been working to clearly identify gully erosion hotspots within the watershed and prioritize mitigation efforts for the many areas suffering from erosion.

Gathering Data from Land and Sky

Gitau and his team took a two-pronged approach to tackle the gully erosion problem. ArcGIS Pro and ArcGIS Online were used in conjunction with satellite imagery for image processing and analysis, while field data was collected with ArcGIS Survey123, a form-based tool for gathering data that runs on mobile devices.

The first step was assessing land-use and land-cover changes in the watershed to determine the causes and extent of gully erosion. To do this, Gitau’s team used ArcGIS Pro to develop deep learning models, assign land classifications, and perform analysis of imagery from Landsat 7 and Sentinel-2 satellites, which are used to map changes in land cover.

The team applied a supervised classification routine and performed a normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) analysis for the satellite imagery. This index is used to monitor vegetation and water levels in a given area over time, and was vital in determining the extent of the damage caused by gully erosion in the watershed.

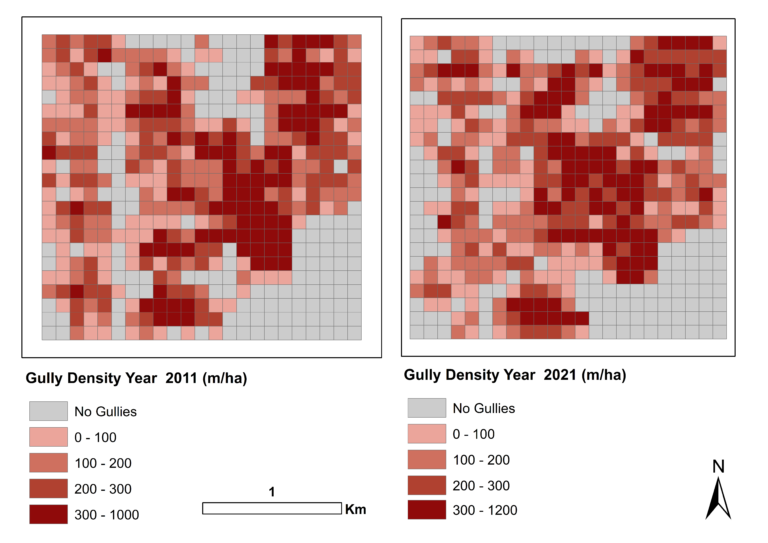

“From the datasets, we were able to quantify the land-cover change at the basin level and analyze the gully density between the 10-year time span,” said Gitau.

The NDVI analysis clearly revealed a massive reduction of healthy vegetation in the Mwatate Watershed between 2011 and 2021 as a direct result of intensified mining and agricultural land use. This expedited the deterioration of healthy vegetation growth, transforming many areas into barren land ripe for gullies.

However, they didn’t rely on satellite imagery alone. Gitau and his team needed to validate the results of their land-cover analysis and used ArcGIS Survey123 to map the coordinates of gullies and note the magnitude of the damage done. They also wanted to collect data that could illustrate the gravity of the problem for policy makers.

“Part of the data was about the extent of the damage,” said Gitau, “but we also wanted to know what type of waste was dumped in the gullies and in the area where we were collecting the data.”

Just as important was taking note of human activities contributing to—and affected by—gully erosion. With Survey123, Gitau and his team recorded where farming and small-scale mining operations were most prevalent upstream and where the activity affected settlements and farms downstream.

Between imagery analysis and field mapping, the team determined that in 2011, there were 826 gullies in the watershed between half a meter and almost 600 meters long. In 2021, the number of gullies had exploded—there were now 1,176, with lengths ranging between one and 725 meters. The area of heavily developed land nearly doubled in that time.

Community Solutions

Despite the scale of the problem, Gitau and his team knew that they couldn’t monitor every area of the watershed indefinitely. Luckily, they were able to coordinate with residents of communities in and around the Mwatate watershed, training them in the use of ArcGIS Survey123 so that necessary data would continue to be collected.

“We created a platform with ArcGIS Online where they could upload the data and we could receive it in real time,” said Gitau. “We receive a notification and are able to follow up and add new information.”

Additionally, the team made several recommendations based on the results of its analysis, such as for the creation of a GIS-based integrated development plan for Taita Taveta County to balance economic development with environmental sustainability. This would include a catchment basin rehabilitation management plan, hillside terracing, and the construction of check dams within gullies to prevent further erosion.

“The county government has backed exercises such as desilting dams,” said Gitau, “and community-led organizations have started cleaning up the gullies, pushing for the use of organic fertilizers in farms upstream instead of the chemical fertilizers that affect the land downstream.”

Gitau and his team have also been developing an early warning system that could alert downstream communities of gully propagation and potential flooding at the watershed with the potential to lead to damage, potentially saving lives and property.

“I’m glad to say that there are efforts in place,” said Gitau. “We can see the fruits of this project, even though it is a progressive project.”