Ireland. The name is synonymous with lush green wetlands and raised bogs, also known as peatlands. But in a country noted for its greenery, less than one percent of the peatlands—about 4,050 acres of an original 760,000 acres—remains in a near natural state. Shaped like a saucer, Ireland’s mountainous coasts form the edges of a central sink, where most of the peatlands remain.

To help monitor the health of the peatlands, Wetland Surveys Ireland (WSI), an environmental consulting firm, uses Esri’s Collector for ArcGIS on iPhones paired with a GPS device called Arrow 100, from Eos Positioning Systems, to collect data about the bogs, ensuring high accuracy as to the location of the area being surveyed. Ireland’s National Parks & Wildlife Service (NPWS) recently began to require WSI to provide submeter accuracy for its vegetation monitoring. NPWS would then have greater confidence that the area WSI surveys one year is the same area that’s surveyed five years later. Having such high accuracy also increases the organization’s confidence in the maps created by surveyors and strengthens political decisions made based on the survey results.

“Having accurate information is important to provide the evidence base required to convince the policy makers [that] we need to conserve these last remaining areas,” said Patrick Crushell, director and senior consultant of WSI.

The peatlands—described by many experts as habitat that’s critical to maintaining a healthy environment—have been in decline in Ireland for many years.

“Ninety-nine percent of these areas have been lost or severely degraded due to drainage associated with peat cutting or conversion to agricultural land,” Crushell said. “It’s a big battle to conserve peatlands in Ireland. We have pressure from the European Union to conserve.”

And for good reason: Ireland’s bogs are some of the world’s best remaining examples of peatland biodiversity. They also provide an ecosystem for water purification and help balance the watershed supply naturally by mitigating flood runoff. A healthy peatland is identifiable by its high water table and almost complete coverage of certain plants and mosses. It’s a “carbon sink,” says Crushell, where peat accumulates at the rate of about 1 milometer per year (or 1 meter per thousand years). These bogs have been growing since the last Ice Age and are more than 10 meters deep.

To conserve the remaining peatlands, NPWS seeks the help of field surveyors such as WSI. By collecting and interpreting data such as water table levels and plant coverage of certain species, WSI can help NPWS officials understand if a peatland is healthy and growing or if it’s degraded. Telltale signs of a degraded peatland include firm soil; a low water table; and the domination of plants associated with drier conditions, rather than species typically associated with peatlands. “Certain species are good indicators of a wet, healthy bog,” Crushell said. “A high cover of these species implies the area has sustained its water table—and sustained it throughout the year. It implies it’s in good condition, or not drying out.”

Tracking the health of the wetlands requires extremely accurate field data collection and monitoring over time. To do this, surveyors such as WSI employees—wearing rubber Wellington boots and waterproof clothing—wade into the peatlands to collect water-table and vegetation information about the bogs by using Collector for ArcGIS. The surveyors measure the incidence of certain species, such as Sphagnum mosses, that are good indicators of a healthy peatland. Surveys of individual bogs are typically repeated after five years to compare the measurements and spot trends in water-table measurements, ground conditions (e.g., firm or soft), slope, topography, and plant coverage.

WSI started to use Collector for ArcGIS on iPhones with Arrow 100 for high-accuracy data collection in 2016. While the company had already been using Collector for ArcGIS for some fieldwork, it was relying on an all-in-one device to perform field data collection that required levels of submeter accuracy. But the cost of replacing those devices every few years to keep up with the evolving all-in-one technology proved too expensive. “They weren’t future proof,” Crushell said.

WSI began looking for a more cost-effective solution that could still provide submeter data monitoring.

Thanks to a 2016 release of Collector for ArcGIS, the Esri app supported connection to high-accuracy external GPS/Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) receivers. When Crushell learned this, he began exploring whether the mobile app used on iPhones could replace the costly all-in-one devices. “There are a lot of reasons I enjoy using Collector [and iOS] instead of all-in-one devices,” Crushell said: “You don’t have to replace your device every few years; the software is continuously updated; [and] the fact [that] it works on any device in our pocket, with the touch screen of an iPhone that’s less cumbersome than some other devices. And Collector itself offers such an ease with which we can create forms on the devices.” In addition, Collector for ArcGIS works in disconnected environments, which offers a huge advantage in Ireland’s remote and rainy peatlands.

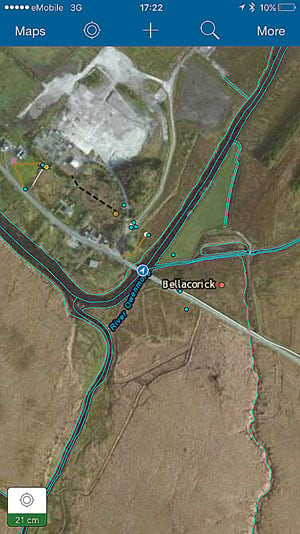

“In peatlands, you’re in the middle of nowhere most of the time,” Crushell said. “With Collector, we can take our data offline and view our aerial imagery. We’re doing that all the time because the cell phone coverage isn’t very good in Ireland. But you can always take the GIS data offline, so it means you can record on your device and sync it at the end of the day.” By connecting Collector for ArcGIS with an external GPS device like Arrow 100, made by Esri Silver Tier partner Eos Positioning Systems and distributed in Ireland by Mobile GIS Services (MGISS), Crushell re-created a field data collection tool that was as accurate as the legacy all-in-ones but only a third of the cost. Arrow 100 taps high-accuracy location data from the European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS), a free European satellite-based augmentation system (similar to the wide area augmentation system [WAAS] in the United States). Arrow 100 sends this information to an iOS device via Bluetooth, and the location data gets populated into Collector for ArcGIS. “The level of accuracy—knowing you’re within a meter of the point you recorded before—gives you a higher degree of confidence,” Crushell said. “This saves us a fortune.”

WSI has discovered that, despite the Irish peatlands’ rapid decline over the past century, recent efforts to reverse the trend have been successful. Policy makers are using the results of the field-collected data to make evidence-based decisions on how to appropriately manage land, continue conserving the remaining peatlands, and reverse their decline.

“We hope that the recent trend continues and that Ireland’s last remaining wet wilderness areas are conserved for the benefit of future generations,” Crushell said.