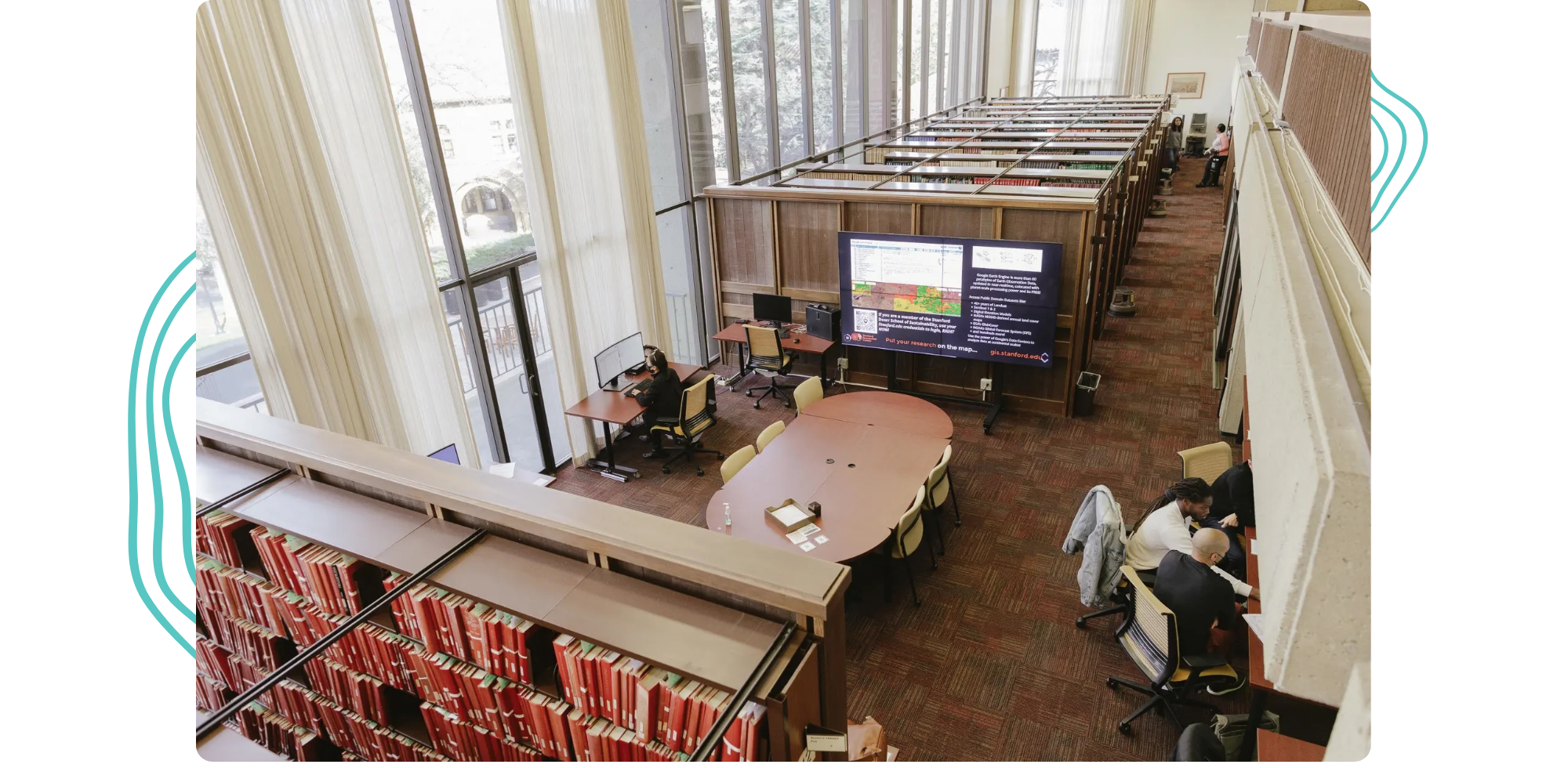

Tucked between the stacks of Stanford University’s Branner Earth Sciences Library and Map Collections is a cluster of high-powered desktop computers, a really big screen, and a couple of guys helping the Stanford community answer questions using GIS. At the core of the Stanford Geospatial Center (SGC) is David Medeiros, Geospatial Reference and Instruction Specialist, who spends his time conducting one-on-one consultations, training users on GIS software, finding spatial data, and helping design spatial analysis.

Data types, topology, projections, coordinate systems, aggregation, layers, visual order, attribute tables, file naming conventions, file paths. It sounds very basic, but that’s exactly it.

Beginning with a career in digital cartography (find him for a hot take on what is and is not a map), David has been serving the Stanford community for 13 years, aligning his industry knowledge and experience with the instructional and research needs of students, faculty, and staff.

With the 2025-2026 academic year upon us, the StoryMaps team recently sat down with David to hear his insight for GIS instructional and research needs in higher education — and his approach to meeting those needs. The following conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

You work with a wide range of students, from undergrads to post-docs. In your experience, what is the general GIS experience level of the students that you encounter?

Undergrads tend to have a very low level of GIS experience. Some may have heard of it; others may have completed a project in high school, but for the most part, it is a new concept to them. For those students who were introduced to it in high school, it was typically a prescriptive assignment in which they completed outlined steps but didn’t walk away with a sustainable understanding of the science behind GIS and its tools.

From graduates to post-docs, a typical scenario is a self-starter who finds their way to documentation or a video on how to complete a specific task, such as network analysis, for example. With these resources, they can get themselves far, but they often encounter a barrier and need help working through it.

A common denominator among both groups is that they generally lack fundamental knowledge of geography and spatial frameworks. So, the more advanced students are still in a similar place to the undergrads as far as their capacity for broadly applying and thinking through GIS concepts and workflows.

Can you give us an idea of what you mean by fundamental knowledge of geography and spatial frameworks?

Data types, topology, projections, coordinate systems, aggregation, layers, visual order, attribute tables, file naming conventions, file paths. It sounds very basic, but that’s exactly it. An example scenario is a student unsuccessfully trying to run an analysis on a layer they found in ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World, leading us to discover their barrier is simply not knowing what type of layer it is, such as an image service versus a feature service, and what they can or cannot do with it.

Students really need a fundamental on-ramp before diving into GIS tools. If they haven’t gone to an introductory workshop yet, I’ll spend more time trying to decipher their questions because they don’t exactly understand what they’re asking or the workflows they’re trying to complete.

You mentioned an introductory workshop. Can you share your approach to bridging the gap between students and fundamental knowledge?

I provide an introduction to GIS workshop in which I spend the first 30 minutes covering the keywords and concepts I mentioned previously. It’s the vocabulary they need to begin having a more effective relationship with GIS — and more understandable conversations with me.

From there, I design the workshop to be a little bit broken so they can begin developing their critical GIS thinking skills.

What do you mean by broken?

For example, I’ll have the workshop present two pieces of data that have different coordinate systems, which leads me to discuss the difference between projection and data coordinate systems with students. These two items can be displayed together and appear to line up correctly. However, if the map is reprojecting on the fly and there’s a lot of data, it will draw very slowly as you pan and zoom. Then I’ll demonstrate this by matching the projection and data coordinate systems, which will enable the map to draw much more smoothly when you interact with it. I find that this method leads to better comprehension of keywords and workflows — and why it matters!

Beyond this introductory workshop, what are other workshops that you provide?

The reality is that most students use Macs, so the logistics of regularly setting up 20 library workstations (Windows) with 20 student profiles and other required installations isn’t practical. This led me to create self-instruction, rather than providing an in-person workshop, for getting started with ArcGIS Pro, which can be found in our group gallery.

Here, our community can find additional self-instruction for topics ranging from ArcGIS Online and StoryMaps to working with paper maps to publication cartography. I find that it is effective to have students run themselves through self-instruction and then follow up with them one-on-one to work through their specific needs.

My colleague, Stace Maples, Assistant Director of Geospatial Collections & Services, teaches Stanford’s Fundamentals of Geographic Information Science (GIS) course, which has been an excellent and consistent touchpoint with students. Along with teaching the fundamentals, the course includes a session on cartographic design led by me and a session on ArcGIS StoryMaps, which students use to bring together and present their final project.

To supplement our instruction and reference services, I also recommend Esri tutorials, which are effective in getting students familiar with the interface and setting them up for more in-depth one-on-one sessions with me.

What is your method for promoting your services and resources?

We’re fortunate to have several faculty members who integrate some GIS expectation into their curriculum, so we have a consistent flow of students each year from those courses — and I would say that about half of those students are intrigued by GIS enough to want to continue growing their understanding and skills.

We also observe the opposite of this, where a student brings GIS-leading questions to their instructor, which leads to the discovery of the SGC for both. And, as part of the Stanford Libraries infrastructure, we frequently utilize built-in tools such as newsletters, event calendars, campus events, and library guides.

Whether they’re coming to you or they’re now on their way, how do you see the Stanford community using GIS in their work?

Two generalized user groups come to mind immediately: those who need to answer a question using GIS and those who need to communicate something using maps. Of course, there is an overlap between these two groups, and sometimes they move from one group to another as their work progresses. The people who need to answer a question or perform spatial analysis tend to require a desktop tool like ArcGIS Pro, while communicators tend to need an online tool, such as ArcGIS StoryMaps. For both user groups, GIS is being introduced and used through course assignments and thesis research, the latter often involving in-depth, multi-year work, so I’ll see those users in the lab for several years.

Beyond students and faculty, Stanford Land, Buildings, and Real Estate (LBRE) uses GIS to manage its assets. After training a group of LBRE staff on GIS and tools like ArcGIS Field Apps, they went on to capture locations of various campus infrastructure and construction projects, creating both internal and public-facing maps.

Another example is the Planet Bee Foundation, which partnered with Stanford Libraries to create the Pollinator Path, a community science project aimed at installing native bee homes. As part of the communicator user group, we utilized ArcGIS StoryMaps to provide basic project information, along with a locator map of the native bee homes.

ArcGIS StoryMaps has been mentioned throughout our conversation. To end, could you summarize how you and other instructors use the tool?

We create most of our self-instruction using StoryMaps, all of which are in our group gallery. It is, ultimately, a quick and easy tool to present instructions with visual aids that we have complete control over, allowing us to modify how and when we need to.

There is a growing number of courses that have implemented StoryMaps as a final project tool. My ideal scenario is when a project requires the student to create an interactive web map, enabling them to fully utilize the tool and achieve the goal of geospatial storytelling, or narrative mapping.

The faculty members who integrate StoryMaps into their curriculum appreciate that it provides a uniform format for final projects from their students, a convenience furthered by base requirements such as the story must have at least one map. I set up ArcGIS groups for each cohort, so the instructor has a designated place to receive assignments, and they can then track the work being completed from year to year.

This featured storyteller interview was prepared as a part of the September 2025 | Back to school—with GIS issue of StoryScape℠.

For more interviews and articles like this one, be sure to check out StoryScape℠, a monthly digital magazine for ArcGIS StoryMaps that explores the world of place-based storytelling — with a new theme every issue.

Article Discussion: