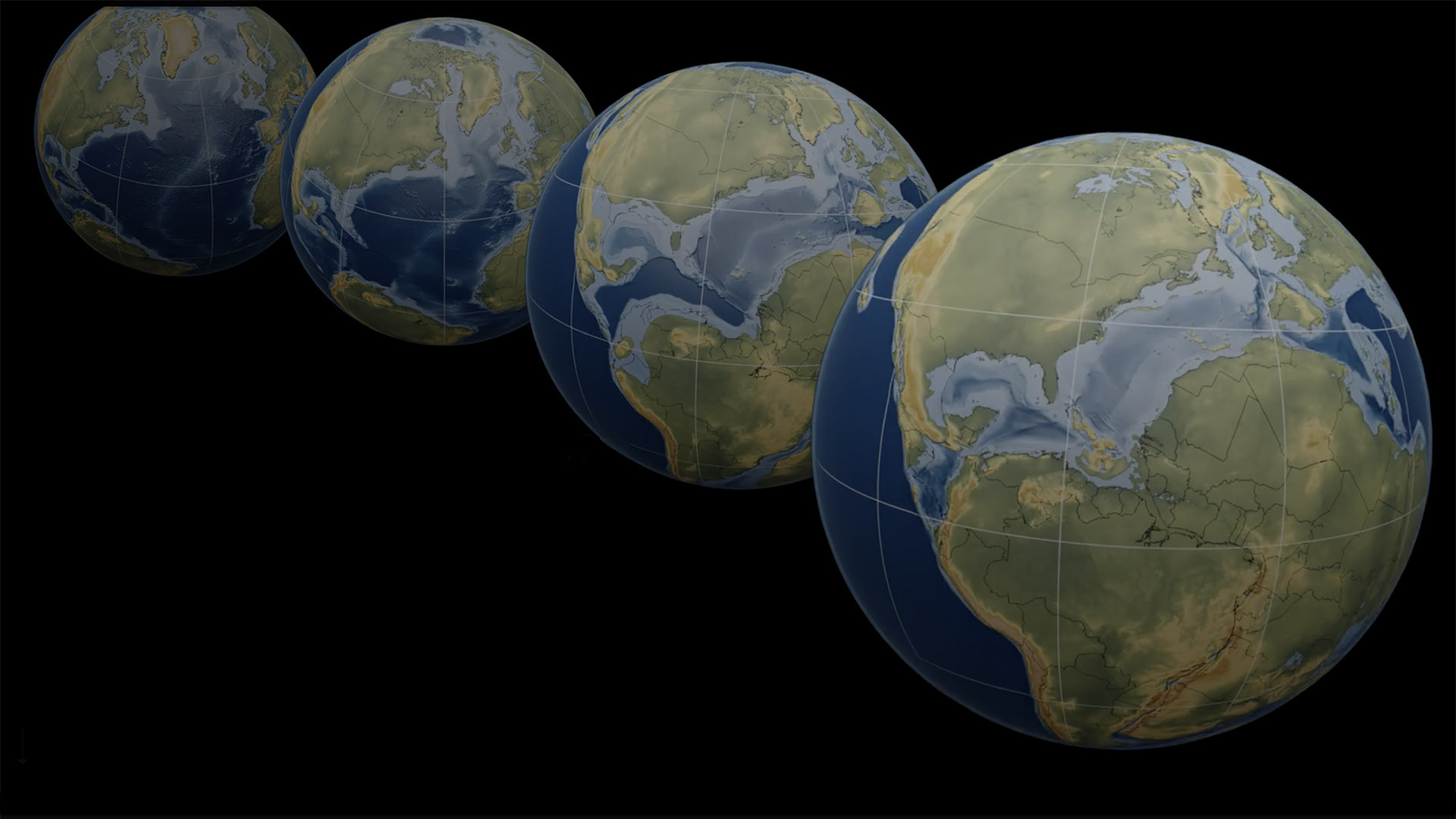

Allen: I’ve long been enthralled by the fact that, over hundreds of millions of years, Earth’s continents have been in constant motion — crawling outward from mid-ocean ridges, sliding past one another, and colliding to build mountain ranges and form supercontinents. I’ve stared at visualizations and animations that depict these movements, usually mapped onto an elliptical projection (Mollweide, to be precise). Much of this work was pioneered by Christopher Scotese, whose paleogeographic plottings have been featured by National Geographic (my former employer) and other media outlets.

As much as I admire these maps and animations, I find them a bit frustrating. Landforms that are close to the edge of the maps are distorted and often split in two. And it’s difficult to relate the movement of the continents to the evolution of life on Earth. Belatedly, I realized that ArcGIS StoryMaps could be the ideal venue to depict this stately continental dance; illustrations could provide a sense of how life was evolving, enduring climate shifts and mass extinctions as the continents crept. Thus was born the idea of depicting the dance of the continents in the form of a StoryMaps narrative. Here’s our story.

Meanwhile, my team and I have long wanted to experiment with a function that some of our users have wished for; namely, the ability to have animations move as readers scroll. We often talk about “map choreography,” but maps in ArcGIS StoryMaps usually jump from location to location, or theme to theme, unless they’re recorded and embedded as videos. The New York Times and other media organizations have done cool things with scroll-driven movement; couldn’t we do it, too, and ultimately, perhaps, enable our users to create their own?

Continental drift seemed to be the ideal topic to bring to life using scroll-driven navigation. So I recruited two technical wizards on my team — Lee Bock and Warren Davison — to prototype this function, using the “dance of the continents” story as a testbed. Meanwhile, Gustavo Cardenas, a designer and illustrator on our team, took on the task of creating line drawings depicting some of the dominant life forms of the various periods depicted on the maps. I now turn this blog over to Lee and Warren to explain their wizardry.

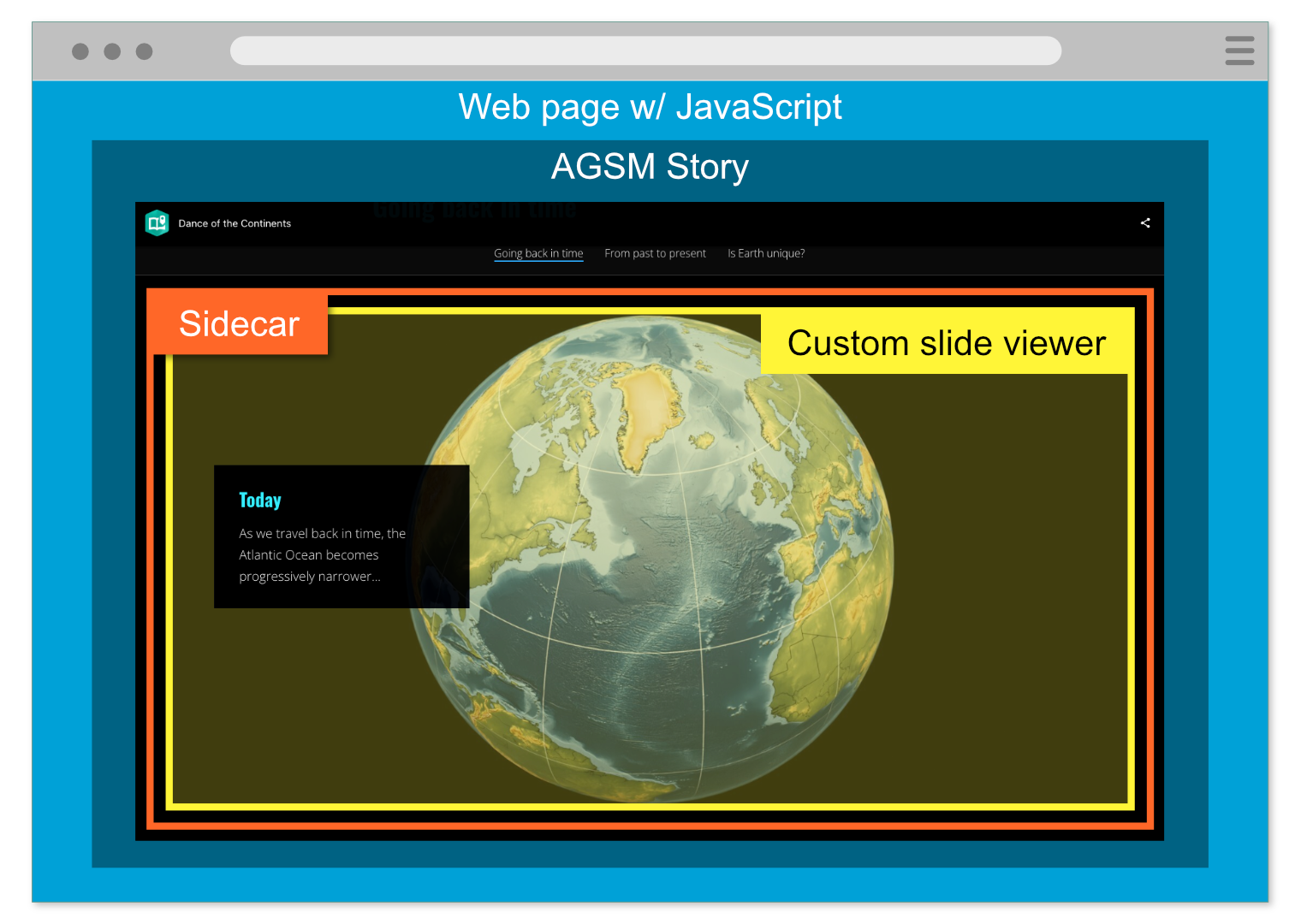

Lee: Since “scrolly animation” is not a built-in function of ArcGIS StoryMaps, this prototype required us to extend the story’s functionality using custom JavaScript — something made possible by StoryMap’s relatively new script embed capability. While script embed is intended primarily to enable seamless embedding of a story in a web page, with a bit of determination you can use it for other kinds of mischief!

Before going any further, I should acknowledge that using script embed to create scrolly animation is… ambitious. The hack described below is more than a little convoluted. But that’s prototyping for you! If you want to explore the code for yourself, you’re welcome to dive into the repo.

With those caveats in place, here’s a high-level walk-through of the configuration.

Hosting

One of the first things you might notice is that the story appears under an unusual domain. Instead of the standard *.maps.arcgis.com, our prototype runs at:

https://esri.github.io/dance-of-the-continents/

This is a direct consequence of needing to host and execute additional JavaScript. Since you can’t host arbitrary script files on ArcGIS Online, we need to place both the container web page and our custom scripts elsewhere — in this case, GitHub Pages.

Important distinction: The story itself still lives on story.maps.arcgis.com; we simply load it into our container page via embed.

Script Embed

We’ve established that our main page is hosted on GitHub Pages and that it loads the story using script embed. Traditionally, you’d embed a story using an <iframe>. Unfortunately, iframes impose strict cross-origin security restrictions that prevent parent pages from interacting with the content inside — a deal-breaker for scrolly animation, which requires our scripts to “see” what’s happening inside the story.

That’s where the script embed capability becomes invaluable: it gives the parent page safe, first-class access to the story’s DOM, making it possible to hook into the story and modify its behavior at runtime.

Double Trouble

Our GitHub Pages site actually contains two different web pages (each with its own codebase):

The primary application URL: https://esri.github.io/dance-of-the-continents/index.html

This page embeds the story, attaches listeners to it, and monitors scrolling. As the reader progresses through the narrative, this application sends messages — via postMessage — to the secondary application.

The secondary application URL: https://esri.github.io/dance-of-the-continents/frames_display/

This is a simple workhorse slide viewer. It listens for incoming postMessage events and swaps out visual “frames” based on the slide index it receives.

If you visit the secondary application directly, it looks like a static, inert web page. That’s because it only changes when it receives messages — not via direct user interaction.

Okay, this next bit is the twist, and I’ve been racking my brain for an icebreaker, so here goes…

Incepted Embeds

Are you familiar with the episode of The Big Bang Theory in which Sheldon builds a “Mobile Virtual Presence Device”? It’s basically a rolling robot with a webcam and a flat-panel display that shows Sheldon’s face. He uses it as a proxy so he can “be present” without actually being in the room. And yes, I know — I should probably update my cultural references.

In any case, the setup reminds me a bit of our application architecture, which involves two layers of embeds. Much like Sheldon’s face is embedded in the robot, our slide-viewer component is embedded inside the story. And here’s the kicker: the story itself is then embedded inside our primary website — just as the robot is… wheeled into the room.

Yeah, that’s the ticket: In this analogy, our main web page is the room. And just as Penny can yell at iPad-Sheldon in response to whatever the robot is doing, our web page can send messages to the slide viewer based on how the user is interacting with the story. I told you it was a little convoluted!

Enough for now

That’s the 30,000-foot view: nested embeds and a bit of JavaScript glue holding everything together. Prototypes like this let us explore what’s possible when you push StoryMaps beyond its comfort zone.

If you’d like to dig deeper, the repo is available. Here’s a little guidance on where to look if you go there.

- Primary application files: html; js

- Slide viewer files (in the frames_display subfolder): html; frame-display.js; js

Warren: As with most things, there’s more than one way to tell a story with StoryMaps. And, for fear of what would happen if I said to Lee, “That was great, but now I need you to do it in reverse,” I took a different approach to the sequence when we returned from 540 million years ago to the present day.

It started with the same renderings that Lee used for the “scrolly animation”, but this time rendered as video files. I then carefully segmented the videos into “chapters” of continental drift, much as movies are segmented into chapters on DVDs (perhaps I also need to update my references). These chapters closely align with the major developments in continental drift discussed in the narrative.

The magic act was now to reassemble these “chapters” in the story. Uploading them in sequence within a sidecar ensured a seamless transition between files, with the files magically playing one after the other as readers scrolled through the sidecar. To make the visual effect more convincing and prevent distraction, the videos were configured to autoplay without looping. Since the sequences animated a few million years at a time, they were just a few seconds in length. Turning off the looping ensured those few million years wouldn’t repeat in a way that would induce motion sickness or fear that our time machine had broken.

All told, the effect works well, and Lee didn’t have to use his JavaScript to reverse time all over again.

Article Discussion: