Sandy Davis, a resident of Cerro Gordo County in Iowa, learned in 2004 that her shaky hands and neurological issues were a result of having unknowingly consumed high levels of arsenic in the water from her private well. Even more disconcerting, she could have prevented long-term exposure simply by testing her water for the known carcinogen.

Davis wasn’t the only person in Cerro Gordo County whose health was at risk from drinking well water that contained more arsenic than the public maximum contaminant level (MCL) of 10 parts per billion (ppb). Nearly 15 percent of the county’s population—about 7,000 people—relies on unregulated private well water. And Davis’s case wasn’t the first time the Cerro Gordo County Department of Public Health had been alerted to elevated levels of arsenic in the water. In 2003, the Iowa Geological Survey and the US Geological Survey discovered the chemical’s presence in every major aquifer in the state. Thus, at the time of Davis’s discovery, the department was conducting a limited public awareness campaign about arsenic in the water, since the agency didn’t have the staff or the funding to orchestrate a targeted drive. Years later, however, GIS helped Cerro Gordo County determine the root cause of its water’s high arsenic levels and, in turn, discern where awareness needed to be raised the most.

Protection Without Regulation

The Cerro Gordo County Department of Public Health aims to guard residents from contaminants in private wells, but this is often difficult because public agencies don’t have the authority or the resources to regularly check well water quality before it flows into household taps. After private wells are drilled, property owners are responsible for maintaining the safety of their own water supplies.

To educate private well owners about the elevated levels of arsenic found in the county’s water system, the Department of Public Health worked with environmental health scientists at the Iowa Department of Natural Resources to develop a mapping tool. Using ArcGIS for Desktop, the department merged its private well water records with arsenic test results and mapped out every known well in the county that tested above the MCL. By doing so, a clear “arsenic zone” emerged on the map, indicating which properties were likely to have arsenic in their private well water. From this, officials created a new ordinance in 2007 that dictated stricter well drilling and testing requirements.

Three years later, with Davis’s story still circulating and public health still at risk, department officials turned once again to GIS for solutions—this time, to locate the source of the arsenic and develop a targeted plan to protect residents’ health.

Mapping a Better Path Forward

To determine whether arsenic-contaminated wells were concentrated in a certain area, the department collaborated with Doug Schnoebelen of the University of Iowa, Paul Van Dorpe and Chad Fields from the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, the State Hygienic Laboratory at the University of Iowa, and private well drilling operator Shawver Well Company. The team received a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to carry out the three-year study.

First, team members pulled geologic information about select (mostly private) wells from the Iowa Geological Survey. The information included data on well and casing depths, well locations, and the aquifers from which water is drawn. Twice a year, the team collected data from 68 test wells on variables that could affect arsenic levels. These factors include the water’s pH, levels of dissolved oxygen, sulfide amounts, total arsenic, and the likelihood of arsenic speciation. The team also analyzed rock chip samples in study wells and all newly drilled wells for traces of arsenic.

As the study progressed, the team learned that half of all the private wells tested had detectable levels of arsenic in the water, and a third of them contained unsafe amounts of arsenic (above 10 ppb).

Using ArcGIS for Desktop again, the department mapped the data to show the geographic distribution of the sample sites plus the arsenic levels at each site. Surprisingly, however, there was no indication that the arsenic-contaminated wells were concentrated in a specific location. But going beneath the earth’s surface revealed a completely different story.

3D Yields Improved Insight

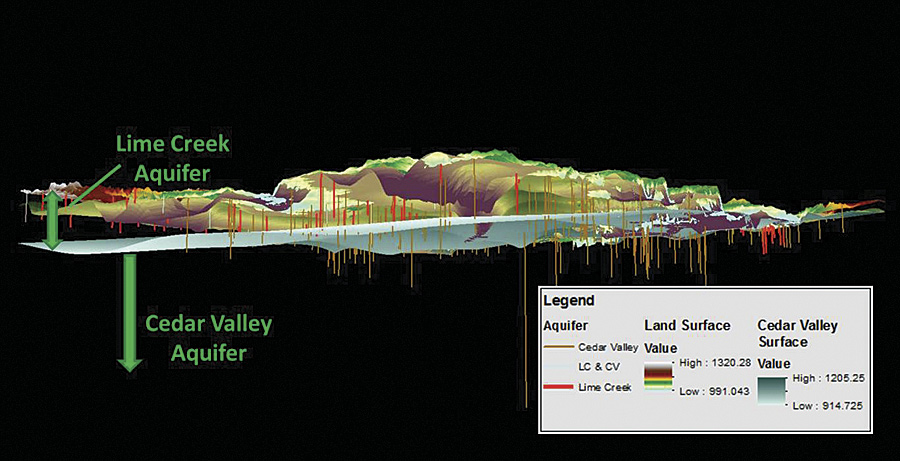

The common thread was uncovered using the ArcGIS 3D Analyst for Desktop extension. The extension’s ArcScene application allowed the team to interact with its geospatial data in 3D for the first time.

“Visualizing our data in 3D gave us insights that just weren’t possible in 2D,” said Sophia Walsh, GIS coordinator and environmental health specialist with the Cerro Gordo County Department of Public Health.

Researchers overlaid the data on arsenic levels with information on well depth, casing, and aquifer elevations. The resultant interactive 3D map let the team see which aquifer each well was withdrawing water from. It turned out that the wells with consistently higher arsenic levels had all been drilled into the same source: the Lime Creek Aquifer.

Though half of all wells countywide were contaminated with arsenic, well water from the Lime Creek Aquifer was much more likely to have unsafe levels of arsenic. The highest measured contamination for wells cased through the Cedar Valley Aquifer, located directly below the Lime Creek Aquifer, was less than 10 ppb, the MCL for municipal water supplies. Rock chip samples from these wells average 1.2 ppb of arsenic. But rock chip samples from the Lime Creek Aquifer showed nearly 10 times that—an average of 11.4 ppb of arsenic.

Geospatial Data Drives Change

Knowing this equipped the Department of Public Health with the critical information it needed to determine which populations were at high risk for arsenic contamination. Using parcel data, the team then geocoded at-risk wells in ArcGIS for Desktop.

From there, the department launched a targeted outreach plan to notify residents of the potential danger in their well water. The team sent postcards and flyers to private well owners recommending that they test their water for arsenic. Department staff followed up with these residents to confirm that they had received and understood the information. According to feedback, 99 percent of the well owners the department contacted said they would treat their well water or use a different water supply.

As Walsh pointed out, the vital role GIS played in this project was twofold: “On the research side, GIS allowed us to figure out which aquifer the arsenic was coming from and begin to construct a model,” she said. “On the public health side, GIS allowed us to find and target at-risk well owners in our community who were sent pertinent information about the risk of arsenic in their water and offered well water testing. Without the use of GIS to research arsenic in groundwater and target specific well owners, there would be hundreds of well users in our community still drinking arsenic-contaminated water.”

Digging Deeper with GIS

But change didn’t stop there. Based on the knowledge gained through this project, Cerro Gordo County is taking measures to improve how wells are drilled. As of July 1, 2015, all new wells in the county must be drilled to use water from the Cedar Valley Aquifer only.

The county is also seeking funding from the National Institutes of Health to develop a web GIS model and predictive database using the ArcGIS platform. The GIS team envisions that the online mapping tool will inform the public about how deep wells should be drilled to reduce the risk of arsenic contamination.

For more information, contact Sophia Walsh, GIS coordinator and environmental health specialist with the Cerro Gordo County Department of Public Health, at (641) 421-9318.