The avatar of a student focuses a red laser simulator at a digital map of Lee County, Florida, in a virtual classroom. He stands with the avatars of fellow students and faculty as he points out where land could be developed near mass transit and urban services and reduce development in areas better suited to agriculture. “Don’t take anybody’s eye out now,” joked a faculty avatar. “I’ll try not to,” the student avatar said with a chuckle before continuing his presentation.

Welcome to the cloud-based environment for teaching geodesign at the Pennsylvania State University (Penn State) World Campus, where students learn to make what the university calls “geospatially oriented” design decisions. Students can earn two online degrees: a 35-credit Master of Professional Studies in Geodesign degree or a 14-credit Graduate Certificate in Geodesign.

Students collaborate on assignments and make final presentations to faculty and classmates in a 2D/3D virtual classroom that provides an immersive environment. Students and faculty also communicate using other Internet-based communication tools such as Skype and Yammer. It’s the next-best thing to being together in one room.

“All our courses are offered online, so people can participate from wherever they are—they don’t have to relocate,” said Kelleann Foster, director of the Stuckeman School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Penn State and the faculty leader of the school’s geodesign program. “So much is happening in the cloud now that it has actually become easier to deliver the program online.”

The online geodesign program was designed for people who work in diverse fields—such as transportation planning, landscape architecture, sociology, hydrology, and urban planning—and who want to use what Foster calls “spatial problem solving” in design decisions.

“It’s geared toward working professionals who want to acquire new skills, advance their [careers], or shift gears,” she said. The time commitment is from 15 to 20 hours per week, Foster said. The Graduate Certificate in Geodesign program takes about a year to complete, while the Master of Professional Studies in Geodesign program usually takes from two and a half to three years.

The online education program is giving Greg King, a GIS consultant from Brisbane, Australia, the opportunity to earn a master’s degree in geodesign from a top school—even if that school is 9,424 miles away in State College, Pennsylvania.

“I’m not aware of any geodesign degrees in Australia,” said King. “Online education works well for me. With my work commitments, being able to study and complete assignments when I have time is the best option. I currently have one class meeting each week, which is fine. But more than that would be a challenge.”

Real-World Geodesign

The class format eliminates challenges, but the assignments are challenging. Students dive in and work on scenarios based on real-world issues that cry out for creative, thoughtful, and scientifically sound geodesign solutions. Recent class assignments have included deciding where to place transit-oriented development (TOD) in Florida and evaluating alternative routes and plans for improving US Highway 64/Corridor K in the Ocoee River Gorge area of Tennessee.

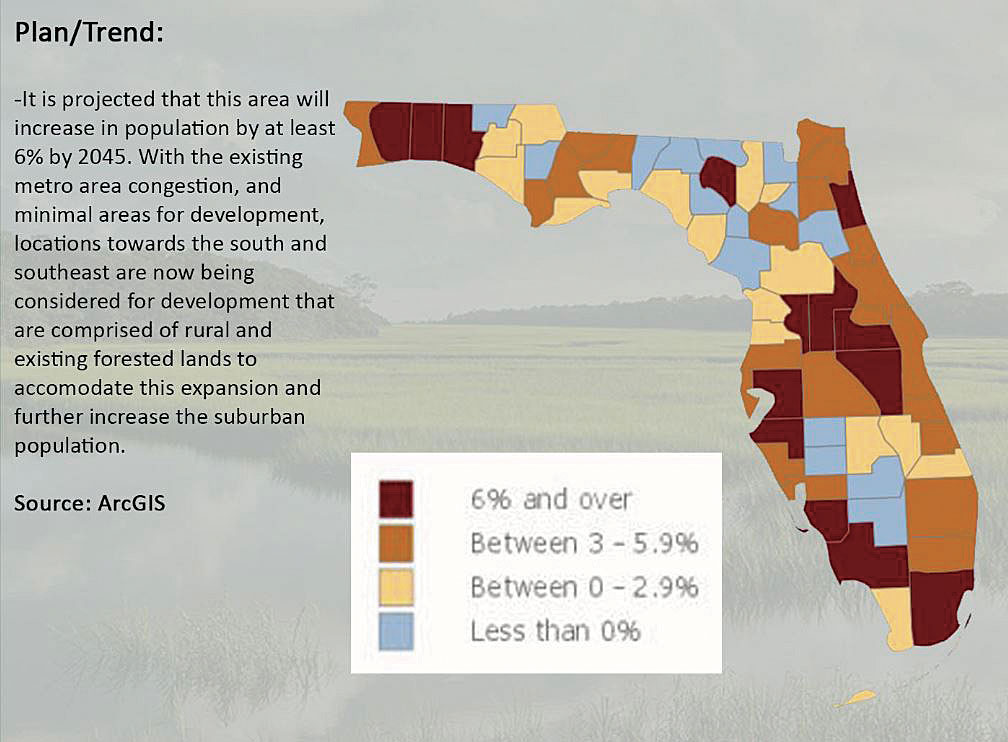

The students use GIS to evaluate their design scenarios. For an assignment for Geodesign Studio I: Rural/Regional Challenges, Penn State faculty member Michael Flaxman stipulated that the students create TOD proposals for various areas of Florida. “[TOD means] the placement of residential and mixed-use development that decreases the total vehicle miles driven and increases the use of public transit,” said Flaxman.

Shannon McElvaney, a master’s degree student, used modeling and analysis tools in ArcGIS for Desktop, ArcGIS Online, and GeoPlanner for ArcGIS to determine where TOD should be located in Miami-Dade County, Florida, in 2040. He took into account the 330,000 households that the county projects will require transportation options by then and the probability that the sea level will be highe

“The question was, ‘where can we grow?'” said McElvaney. He had to factor in many constraints: protecting green infrastructure, accounting for projected sea-level rise, and land that was unsuitable for development. Using sea-level rise projections available online from The Nature Conservancy, McElvaney brought that data into GeoPlanner for ArcGIS and mapped it. The map he created showed the land in his study area that would be covered by water in the future due to a projected three-foot rise in sea level. This would mean big trouble for portions of Miami Beach and a military base to the south.

“I couldn’t believe how drastic it was and how much land it overtook,” McElvaney said during his final online presentation. He finally decided to develop a bus rapid transit system farther inland and create mixed-use development along that route rather than putting in a fixed rail system that may be threatened by the rising sea level.

Flaxman said he was impressed with the work done by McElvaney and the other students in the class. “The primary [objective] was to become comfortable with large problems and large spatial scales,” said Flaxman, who also has taught at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and owns Geodesign Technologies Inc. in Berkeley, California. Students had to understand the plans and trends in their assigned regions and strategically intervene to improve the plans. “They came up with some good design solutions that faculty wouldn’t have thought of,” Flaxman said.

A Well-Rounded Education

The Penn State geodesign program is not meant so much to turn out a cadre of geodesigners as it is to give people in their chosen professions the skills to lead a geodesign process, according to Foster.

“They don’t have to be a GIS expert. They have to understand GIS,” Foster said. “They don’t have to be a design expert, [but] they have to understand the design process.”

Flaxman agrees. “Those with the [geodesign] training are going to do their traditional jobs better,” he said.

Both the certificate and master’s degree programs require geography courses as needed, along with classes on geodesign history, theory, principles, and models. The master’s degree students also take Geodesign Studio I and II and complete a capstone experience that involves preparing a student-selected, peer-reviewed geodesign project and then either presenting it in a formal venue such as a conference or author an article about it for a professional publication.

Whether students leave the Penn State World Campus with a master’s degree or certificate, Foster hopes they will carry with them a thorough understanding of a design process that includes gathering input from stakeholders, obtaining and analyzing data related to the issue, evaluating design proposals, and studying the consequences and implications of each proposal based on a set of criteria that is established early on in the process.

“What I think is so powerful about geodesign is [that] once you know this process, it’s transportable,” said Foster. “You can apply it to many different situations. And even as the technology changes and evolves—which, it does, every year—you will know how to plug the newest technology and newest ways to acquire the data into this framework in order to go forward with decision-making and [getting] the rapid feedback on the impacts and potential consequences.”

The days of working in a vacuum on a design project without collaborating with the public, decision-makers, and experts in other fields are long gone. “That is so oldschool, especially with place-based projects,” she said. “You have to be able to understand how to work with a variety of people. To ask the right questions and get the right information from them is essential to the outcome.”

Otherwise, design proposals can turn into dinosaurs. “We have a lot of beautiful plans that sit on shelves because they weren’t part of a process that people were brought into and [where people] understood the value of the outcome,” Foster said.

For more information about the Penn State Master of Professional Studies in Geodesign and Graduate Certificate in Geodesign programs, visit worldcampus.psu.edu/geodesign or contact Kelleann Foster.