Geodatabase Technology Guides Global Land Mine Removal Efforts

Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining Helps Countries Eradicate Dangerous Remnants of War

Highlights

- An ArcGIS software-based application organizes information for safer removal of ground explosives.

- An information management system ensures efficient distribution of demining personnel and assets.

- With minimal effort, Afghan Mine Action Programme creates the largest single demining database on record.

In recent years, statistics show that the danger of land mines persists long after the smoke of combat clears. According to the United Nations (UN) Mine Action Service, approximately 4,000 people worldwide die or receive injuries from land mines or unexploded ordnance per year (a reduction from 10,000–15,000 15 years ago). Because militaries do not traditionally plan for the clearance of minefields when conflicts end, thousands of acres of mined ground currently endanger civilians in many parts of the world.

In recent years, statistics show that the danger of land mines persists long after the smoke of combat clears. According to the United Nations (UN) Mine Action Service, approximately 4,000 people worldwide die or receive injuries from land mines or unexploded ordnance per year (a reduction from 10,000–15,000 15 years ago). Because militaries do not traditionally plan for the clearance of minefields when conflicts end, thousands of acres of mined ground currently endanger civilians in many parts of the world.

Land Mine Ban

Those statistics prompted the adoption of the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention (the Ottawa Treaty) in 1997 banning land mine use, transfer, and stockpiling within those countries that signed this landmark treaty. To date, 156 states have ratified the convention.

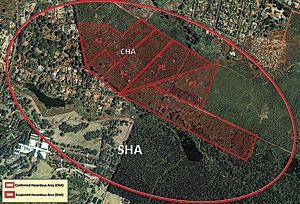

Example maps of the hazards area (top) and land release (bottom) processes. The original area is divided into polygons with varying levels and types of threat. The area not considered to be contaminated is released as cancelled land.

The size and scale of the problem of mine and explosive remnants of war requires an enormous international effort to achieve the aim of a mine-free world and a return to safe and productive use of affected land. This involves national mine action authorities in affected countries, donor governments and organizations, the UN, and other partners.

One international nonprofit organization that has made significant efforts in supporting the work of the convention and affected countries is the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD). Created as a Swiss foundation and supported by many other countries and partners, GICHD is the leading center of expertise on mines, cluster munitions, and explosive remnants of war and helps governments of contaminated countries implement the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention and other related international laws. GICHD provides advice and capacity-building support, undertakes applied research, disseminates knowledge and best practices, and develops professional standards.

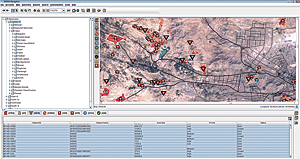

In 1998, GICHD enlisted the help of Esri and a team of GIS programmers to create a single database application for all demining projects that can be tailored for individual cleanup efforts. Called the Information Management System for Mine Action (IMSMA), the software incorporates ArcGIS and plays a central role in mine action in more than 50 countries. GICHD earned the Making a Difference Award at the 2011 Esri International User Conference for its technological assistance and GIS training of mine removal teams around the globe.

Populating the Database

Before a mine-clearing project starts, all relevant information about the specific conflict must be available for input into the IMSMA database. The process of gathering this information includes monitoring an ongoing conflict to make all potentially relevant information available to everyone in the demining community of a particular region. All paper data, such as maps, field records, and witness reports from each individual country, must first be digitized and input into the database. "ArcGIS is ideal to provide an overview of contamination because it is inherently organizational," says Daniel Eriksson, head of information management at GICHD. "GIS naturally excels in situations where much information has to be logically organized and immediately available for processing with geospatial tools."

Prepping for the physical work of neutralizing a minefield can take years but makes the decontamination process more accurate and, thus, safer. A preliminary gathering of data and quality control helps build up the database on a certain region to prepare for actual mine cleanup. Eriksson emphasizes the information management side of GIS software as being just as important as the geospatial side. "A digital map is only as good as what it claims to represent," says Eriksson. "You can have a very fancy-looking map that's useless—even dangerous—for demining work if populated with erroneous data."

Preliminary data gathering largely consists of teams conducting surveys to refine the information that will eventually populate the map. "Being nonspatial processes, surveys do not lend themselves well to display on a map," says Eriksson. "Good information management ensures traceability of past surveys conducted on an area, verifying the quality of the information and resulting in more accurate maps." More accurate maps translate into more efficient distribution of demining personnel, heavy equipment, and explosive-detecting animals. GIS ultimately reduces human suffering by making sure that minefields are being identified and removed with the right tools in the right order.

Kosovo

Nowhere has that been more effectively demonstrated than in Kosovo, which was declared impact free from land mines in 2001. To coordinate survey teams and mine awareness groups with the multiple nongovernmental organizations that carried out the actual demining, the Kosovo mine action coordination center (MACC) had to process vast amounts of raw data for inclusion in the IMSMA database and then distribute that information to field-workers in near real time. That system of quality control and database creation helped rapidly identify and address the majority of Kosovo's minefields compared to manual methods of organization and analysis.

IMSMA was particularly helpful in verifying true minefields over rumored ones in Kosovo. For example, if Kosovo civilians observed something that seemed to be a land mine in a field, that field could be branded a minefield on assumption. When rumors start about subjects as frightening as land mines, people tend to exaggerate the size of the affected area when reporting it to authorities—or even create imaginary minefields where none exist. In IMSMA, multiple civilian reports can be checked against survey records and field records to determine whether land mines are likely to populate a given area. If so, survey teams of deminers can be assigned to collect more information and fence the area to prevent accidents until clearance assets are available. Other fields were mined so sparsely that the MACC deemed full-scale clearance unnecessary. Determining the mine density and patterns in each field ensured an efficient distribution of assets.

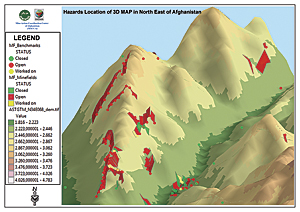

Exploratory 3D analysis of land mine contamination in Afghanistan. Maps like these help decision makers prioritize work and develop plans for how to address contaminated areas (image courtesy of Hansie Heymanns).

Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, GICHD trained staff at the Afghan Mine Action Programme, providing the country's MACC with a standardized repository on contaminated fields throughout the country. Everyone participating in a mine action project—survey takers, deminers, and those involved with mine risk education of locals and assistance to land mine victims—gathers the same information from every area and submits it to the IMSMA database. Using this standardized data, IMSMA allows coordinators to dramatically increase their overview and the efficiency of their decisions. Managers can analyze data, view graphs and charts of all data, plot geographic maps of minefields, keep track of all mine action activities, and view compilations of any statistics they wish.

The Afghan land mine dataset contains nearly 60,000 records and is growing, with 1,000 new field reports from seven regions entered each month. Training the Afghan Mine Action Programme staff to use IMSMA allows them to handle all mine action data for Afghanistan. The team is equipped to coordinate incoming data from field operators by offering adapted data validation and synchronization, resulting in the creation of a single database with minimal effort.

IMSMA's Further Potential

IMSMA was created to help the demining community manage its information better. Most countries and organizations had staff with limited computer literacy, and each country had different information needs. This called for a very intuitive system that still offered almost total flexibility in what data should be collected and analyzed. The inherent flexibility of IMSMA makes it naturally applicable to other crises, such as earthquakes and floods. "In the future, I can see IMSMA being used for other humanitarian purposes," says Eriksson. "Instead of tracking minefields, we'd be able to track which collapsed buildings should be rebuilt first by checking against relevant information in the database." For now, however, Eriksson is committed to finishing IMSMA's work in demining.

IMSMA has played an integral role in several countries that have subsequently officially declared themselves land mine free, but much work still remains. "We have a lot to be happy about in terms of enabling countries to eradicate these dangerous objects faster," says Eriksson. "However, I'm convinced that we've barely scratched the surface of what is possible with GIS in humanitarian aid."

For more information, contact Daniel Eriksson, Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (e-mail: d.eriksson@gichd.org).