Integrating Scientific Research with Indigenous Knowledge in Arctic Alaska

By Wendy R. Eisner, Department of Geography, University of Cincinnati

Highlights

- The elders of the North Slope Borough are keenly aware their way of life is under siege.

- Investigators combined remote sensing, GIS, field data collection, and I�upiaq ecological knowledge to study landform processes.

- A Web site was created to be an open portal to access the I�upiaq Web GIS.

Living in one of the harshest environments on earth, the I�upiat Eskimos of the Alaskan North Slope have a more intimate relationship with their land than most of the world's people. They are heavily dependent on hunting and fishing for much of their food, and they must be highly trained to cope with environmental extremes: winter temperatures of -40�C, blizzards, dense fog, and hoards of mosquitoes. Their lifestyle demands that they be cognizant of the potential hazards of traversing their land, since mistakes can be life threatening. Adding to these hardships, the I�upiat are witnessing unprecedented environmental changes that are often beyond the experience of seasoned hunters and elders. They watch the landscape with concern: the lakes are draining, the permafrost is thawing, and the coastline is eroding. They must now adapt to changes that are rapid and unpredictable. To top it off, climate change has been more pronounced in the Arctic, causing greater disruption to landscape, vegetation, and animals than anywhere in the world.

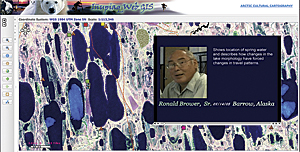

This satellite image clearly shows that the landscape is densely covered with lakes. The inset shows an example of a linked video clip of an elder describing one of these lakes.

The I�upiat are profoundly tied to their environment not only through their subsistence lifestyle but also their cultural identity. The elders of the North Slope Borough (a Wyoming-sized region of northernmost Alaska with 10 villages and 7,500 people) are the custodians of all accumulated environmental and cultural knowledge. They have expressed concern about the changing landscape, interest in scientific findings about those changes, and a desire to share their knowledge of local ecosystems with scientists. They are aware that their way of life is under siege and that they represent a vanishing breed. Community members of all ages have indicated that they want the ecological and historical knowledge of their elders to be documented and archived for future generations.

Because much of their knowledge is location-specific, one way of achieving this goal has been through the creation of a GIS database of indigenous knowledge. Fifty-two I�upiat elders, hunters, and berry pickers from the villages Barrow, Atqasuk, Wainwright, and Nuiqsut were interviewed, and more than 50 hours of videotaped interviews were produced. During the interview, an elder would identify a location using topographic maps and satellite images. Observations on the landforms, environmental change, human activities, and other phenomena were geocoded and entered into the GIS. Some of the major categories or features were classified as drained lakes, freshwater springs, erosional features, resources (caribou, fish, berries), historic sites, and travel routes. The dataset was created using ArcGIS Desktop applications through an Esri university site license agreement.

The impetus for this project grew out of the environmental research conducted by a team of scientists interested in the landscape evolution of the Arctic tundra. For more than two decades, geoscientists Wendy Eisner and Kenneth Hinkel of the University of Cincinnati, Ohio, have been studying the Arctic Coastal Plain of northern Alaska, which includes the North Slope Borough. The dominant landscape process in this area of continuous permafrost is the formation and drainage of lakes. In 2004, Eisner, Hinkel, and University of Georgia collaborator Chris Cuomo began to explore the intersection of I�upiaq knowledge and landscape-process research in the Arctic. With support from several programs at the National Science Foundation, they combined remote sensing, GIS, field data collection, and use of I�upiaq ecological knowledge to study landform processes. One of the unique aspects of this project was the combination of western science with traditional knowledge. The material obtained greatly exceeded the original scope of the project and has expanded into wider realms, including life stories, cultural history, and human impacts on the land.

An important goal of the project was to develop a methodology for returning this body of knowledge to the local community for use as an educational and resource management tool. The Internet permits the seamless transfer of data and knowledge and has the ability to reach a large number of people. To that end, the I�upiaq Web GIS was incorporated into a Web-based platform using ArcGIS Server.

While it was deemed important to create a Web site with a number of spatial analysis tools, it was also important to understand the stakeholders involved. Many people of the North Slope have limited Internet access and computer/technological knowledge. Thus, the layout of the I�upiaq Web GIS is straightforward, containing a table of contents, overview map, basic toolbar, main map viewer, and advanced toolbar. The inclusion of links to video clips of interviews is another feature of the Web GIS.

A Web site, Arctic Cultural Cartography (northslope.arcticmapping.org), was created to be an open portal through which the I�upiaq Web GIS could be accessed. Since the information contained in the GIS has the potential to be culturally or politically sensitive, the proprietary rights of the owners needed to be addressed. To ensure that the data remains secure, the portal site is public, and users are asked to register for access to the GIS.

The information in the I�upiaq Web GIS represents only a portion of the database that has been collected. This is a demonstration site, and it is anticipated that the feedback received from visitors will lead to the development of a complete interactive site in the near future.

The people of the Arctic have witnessed rapid and catastrophic changes in the landscape during their lifetimes. Their insights provide a level of understanding that is not often available through traditional scientific methods. By providing the means for the stakeholders to participate in this process, it is anticipated that the community will assume control of data collection, thereby preserving their own culture and creating a living document.

About the Author

Wendy Eisner, associate professor of geography at the University of Cincinnati, Ohio, was the principal investigator of this National Science Foundation project.

Acknowledgments

Ken Hinkel, professor of geography, University of Cincinnati, Ohio, and Chris Cuomo, professor of philosophy and women's studies at the University of Georgia, were coprincipal investigators. Jessica Jelacic earned a master's degree from the geography department, University of Cincinnati, for her thesis on the development and implementation of the I�upiaq Web GIS. Dorin del Alba, Integrative Group, Fairbanks, Alaska, is an IT Web consultant who designed the Web site, and Changjoo Kim, assistant professor of geography, University of Cincinnati, lent his expertise to the realization of the Web GIS. This project would not have succeeded without the cooperation and dedication of a number of other people, not least the I�upiat people of northern Alaska.

For more information, contact Wendy Eisner (e-mail: wendy.eisner@uc.edu). Visit the Arctic Cultural Cartography Web site at northslope.arcticmapping.org.