What Makes New York's Shawangunk Mountains One of the "Last Great Places"?

By John Thompson, Director of Conservation Science, Mohonk Preserve, Inc.

Highlights

- GIS maps demonstrate the relationship between rare species and their habitats.

- With GIS, scientists and managers illustrate and describe the importance, requirements, and changes in ecological communities.

- GIS analysts used ArcGIS to identify and describe ecological threats and then prioritize restoration strategies and actions.

![]() Due to its rich biological diversity, New York State's Shawangunk Mountains region is one of the most important sites for conservation in the northeastern United States. Because of the many rare natural communities and species found here, the New York Natural Heritage Program ranked the Shawangunks highest in biological diversity, and The Nature Conservancy recognized them as one of the "last great places" on earth. The northern Shawangunk Mountains support 42 state rare species, eight state rare ecological communities, and three globally rare ecological communities in a largely forested landscape surrounded by residential housing and agricultural uses.

Due to its rich biological diversity, New York State's Shawangunk Mountains region is one of the most important sites for conservation in the northeastern United States. Because of the many rare natural communities and species found here, the New York Natural Heritage Program ranked the Shawangunks highest in biological diversity, and The Nature Conservancy recognized them as one of the "last great places" on earth. The northern Shawangunk Mountains support 42 state rare species, eight state rare ecological communities, and three globally rare ecological communities in a largely forested landscape surrounded by residential housing and agricultural uses.

Vegetation change was analyzed using GIS. Aerial photo interpretation was digitized from both 1948–50 photos and 1994 photos. Cross-hatching shows areas of ridgetop pitch pine barrens in 1948–1950; tan areas show current pine barrens. One-third of pine barrens became forest between 1950 and 1994.

This is a surprisingly rugged landscape, with cliffs up to 350 feet tall topped by pine-dominated crags sloping into steep hemlock ravines. Though 27 million people live within 100 miles of the northern Shawangunks, the mountains support a rather wild landscape. The sustainability of this unique area in an ever-changing world is dependent on the cooperation of scientists, land managers, and the public. GIS provided a comprehensive tool to visualize and understand this intricate landscape.

Why is this area so ecologically rich? The ridge-forming bedrock, Shawangunk Conglomerate, is resistant to erosion but has been faulted and jointed through plate tectonics. Glaciations wore away bedrock around the conglomerate, shaping cliffs, scooping out mountaintop "sky lakes," and forming waterfalls and ice caves. The sharp relief, varied soils, and ecological dynamics of this landscape create the foundation for the diverse mosaic of natural communities that occur here.

Conservation on the ridge began with the accumulation of property by mountain resorts, at both Mohonk and Minnewaska Lake, established in the 19th century by twin brothers Albert and Alfred Smiley (see "Mohonk to Redlands: The Smiley Connection"). The resorts promoted people's relationships with nature and each other. As mountain farms were abandoned, the mountain resorts purchased the surrounding lands to add to their holdings. Eventually, the resorts grew to own nearly 20,000 acres. With time, the regional resort industry declined; the only resort still surviving is the Mohonk Mountain House.

In the mid-20th century, interest in protecting this rare ecosystem grew. In 1963, the Mohonk Trust was formed by Smiley family members (descendants of the Smiley twins) and friends to provide conservation, education, scientific research, inspiration, and recreation. The trust began its existence by acquiring outlying lands of the Mohonk Mountain House, eventually becoming the Mohonk Preserve and growing to nearly 7,000 acres. Most other large landholdings have become part of what is now Minnewaska State Park Preserve, a refuge over 20,000 acres in extent.

In the 1980s, some land managers began working together, realizing that they faced similar challenges. But landholdings were large and complex. The Shawangunks have been studied for more than 100 years, and land management was done mostly by "gut feeling."

Composed of nonprofit and public organizations, the Shawangunk Ridge Biodiversity Partnership uses science and land management strategies to preserve sensitive wildlife habitats and other natural resources of the Shawangunks. The partnership formed in 1994 as a collaboration of Cragsmoor Association; Friends of the Shawangunks; Mohonk Preserve; New York-New Jersey Trail Conference; New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; New York State Museum; New York State Natural Heritage Program; New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation; Open Space Institute; Palisades Interstate Parks Commission; The Nature Conservancy; and US Fish and Wildlife Service. The initial step for the partnership was to inventory and map rare species and habitats in ArcGIS. By mapping the vegetation communities and descriptions into ArcGIS, partners could then visualize how the pieces fit together through shared maps.

The partnership has used ArcGIS to identify and map the key ecological communities of the ridge and the greatest threats to their long-term sustainability. As it turned out, many of the original intuitions were largely correct, but scientists and managers, through GIS maps, could illustrate and describe the importance, requirements, and changes in ecological communities that each organization needed to understand to effectively manage and communicate to their constituents. Partners developed a cooperative, ridge-wide plan to preserve the beauty and ecological integrity of more than 40,000 acres of the Shawangunks while maintaining high levels of public access and enjoyment and sharing natural resource information on surrounding properties with local towns.

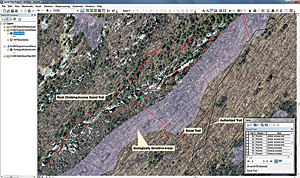

Unauthorized, or "social," trails often run through ecologically sensitive areas. Land managers are comparing recreational impacts to fragile natural resources to identify problem areas and develop mitigation plans.

Using science to inform and conduct land management, the partnership has inventoried and mapped the forests, barrens, and wetlands in and around the ridge. The first set of partnership guidelines was developed for managing the land and all its resources as one integrated landscape. Prior to the formation of the partnership, focus had been on individual rare plant and animal populations and patches of rare communities. Thorough mapping and analyses, along with "seeing the big picture," showed the importance of the matrix forest in protecting conservation targets—biological connections between rare communities became more apparent. The timing and extent of historic disturbance events, such as wildfire, wind, and ice storm damage, are being mapped and are better understood through space-time analyses.

An important finding of these studies is that areas of disturbance-dependent natural communities are stable for long periods of time on shallow soils, even in the absence of disturbance events. Ecological threats, such as encroaching development, forest fragmentation, and invasive species, were identified and described by GIS. While depicting the threat of these stressors (current extent and potential impacts), GIS is used to prioritize restoration strategies and actions. Visualizing the ridge as a whole will help ensure the survival of the sum and all its parts.

About the Author

John E. Thompson was appointed as director of Conservation Science at the Mohonk Preserve this year and oversees the Daniel Smiley Research Center, a world-renowned natural history collection. Thompson has been using GIS for biological conservation for nearly 20 years.

For more information, contact John Thompson, director of Conservation Science, Mohonk Preserve, Inc. (e-mail: jthompson@mohonkpreserve.org).

See also "Mohonk to Redlands: The Smiley Connection."