ArcUser

Spring 2012 Edition

Improving Citizen Engagement

GIS fosters participation

By Monica Pratt, ArcUser Editor

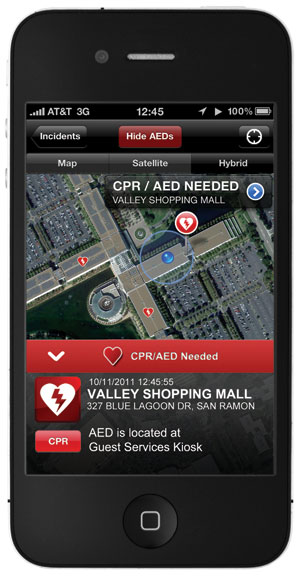

When a call for CPR comes into the San Ramon Valley Fire Protection District, the Lifesaving App, available for Android and iPhone smartphones, notifies the nearest available volunteer to come to the rescue.

This article as a PDF.

GIS-based civic engagement apps are improving the performance and image of government by helping citizens actively participate in government on their terms.

In recent years, citizens' expectations of government have changed radically. In response to perceived shortcomings of government, they have become impatient. These shortcomings can be categorized broadly as unresponsiveness, inefficiency, and lack of accountability and transparency. At the same time that citizens need and want more from government on all levels, governments are operating with fewer resources and dealing with systemic issues such as failing infrastructure.

Citizens' impatience with government is also a by-product of the profound transformation in their interactions with businesses, family, and friends. Thanks to smartphones and tablet devices and ubiquitous access to the Internet, these interactions have become on demand and customized. Impulse is quickly connected to action. People have become accustomed to buying anything from a jar of skin cream to a major appliance with just one click. Through social media, they just as quickly and effortlessly stay in nearly constant contact with friends and relatives—no matter where they live.

Thanks to the prevalence of these devices, concerns about the digital divide that were the centerpiece of discussions about putting government information on the Internet a dozen years ago are largely moot. Privacy concerns also seem to be a nonissue for younger generations who are comfortable sharing almost any information.

In contrast, traditional ways of interacting with government—writing letters, attending town meetings, participating in focus groups—seem cumbersome at best and exclusionary at worst and don't provide timely feedback. In addition, current methods used by government for communicating with citizens are unidirectional. This reinforces the impression that government isn't listening. In this era of social media, communication between government and governed should be a conversation.

Consequently, just pushing back-office applications out to the public-facing web will not meet the needs of citizens. The defining characteristic of a civic engagement app is its bidirectional nature. No matter the purpose, apps should incorporate a feedback mechanism that communicates not only citizen concerns but also government response.

Creating these apps requires understanding what citizens need and want and supplying it quickly. Instead of building monolithic apps designed to last, a more successful strategy is to make disposable apps that are rapidly created, used for a time, and discarded.

Two types of apps are emerging. The first type complements existing government services and makes them more accessible. The second, more intriguing type encourages people to work closely with government to do things no one had thought of doing before, like rounding up volunteers to clean beaches after a holiday weekend.

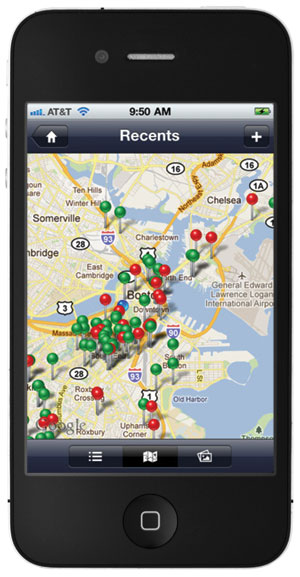

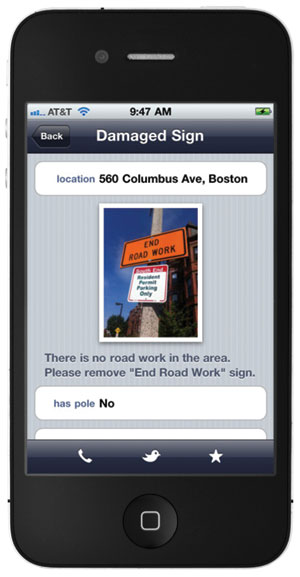

Reports sent using the Citizen Connect app for iPhone and Android smartphones are automatically fed into the City of Boston's work order system. Residents can use the assigned tracking number to check on a request's status.

Other entities, with a variety of agendas, have also begun producing civic engagement apps. These entities can be startup companies, social-minded organizations, not-for-profits, and traditional GIS partners. Some companies seem dedicated to disrupting government, while others develop civic engagement apps to gain a competitive edge. In most cases, the apps are not integrated with government workflows. To the citizen, these apps appear to work, but because they don't furnish information in a way government systems can easily use, the information they provide is not easily acted on by government.

Embracing civic engagement apps brings new challenges and opportunities for GIS managers in local government. A compelling argument for taking ownership of civic engagement apps is to avoid problems stemming from poor integration with back-office processes and take advantage of new sources of geospatial information.

With these apps, usability is of paramount importance. Conventions of a typical GIS interface design may need to be abandoned in favor of ones that use interactions citizens will be familiar with. Another challenge associated with civic engagement apps is the design of workflows that take advantage of new sources of geospatial information and are integrated with business processes.

Rather than replacing the work of traditional GIS, these apps make the maps and data produced by GIS departments more useful and accessible to more people both inside and outside government. These apps also elevate the value of the authoritative data produced by government GIS departments as people become dependent on obtaining current, accurate data.

Beyond these general patterns of app development previously cited, civic engagement apps fall into seven categories based on the type of interaction they encourage: public information, public reporting, solicited comments, unsolicited comments, citizen as sensor, volunteerism, and citizen as scientist.

Civic engagements apps have the potential to enlist new segments of the population—people who had not previously participated in government—and bring their concerns, insight, energy, and commitment to reinvigorate government. This is an exciting prospect.

See also "Civic Engagement Apps Fall into Seven Categories."