GIS Technology Helps Rid Southeast Asia of Dangerous Land Mines and Unexploded Ordnance

By Carla Wheeler, ArcWatch Editor

In Laos, they call them "bombies."

It's an innocuous-sounding name for the small cluster bomblets that lie in the ground, silent and harmless, until someone accidentally awakens their deadly force.

This winter in the province of Savannakhet, Laos, that happened to nine someones. A group of young girls and boys unearthed a Vietnam-era bombie, which often resembles a bright-colored ball or piece of fruit. The explosion and flying metal killed four of the children and injured five.

"The story is terribly sad," said Arleen Engeset with Norwegian People's Aid (NPA), a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that supports demining operations in several countries. "The kids were playing and dug up the cluster bomb. It was just behind their houses."

While not a deminer, Engeset works to rid Southeast Asia of those deadly types of cluster munitions and land mines using a special set of skills: her project management and GIS expertise.

As NPA's advisor on information management systems in the Southeast Asia region, Engeset is helping create or update national databases that will contain a wealth of information about land mines and unexploded ordnance (UXO), to wit: where accidents have occurred, hazardous sites with confirmed mines or UXO, suspected contamination areas, and land already cleared. Using GIS technology, this data is quality assured, mapped, and analyzed, and the results form the basis for deciding where, when, and if certain areas of land need to be demined.

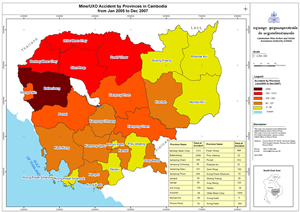

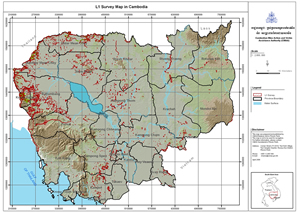

The red areas on this map indicate the findings from the National Level One Survey in Cambodia, where people reported the existence of land mines or UXO. Image courtesy of CMAA. |

"GIS is playing a big role because we get an overview of where the most accidents are, where the most people are living, and where the biggest problems [exist]," Engeset said.

By considering those factors, priorities can be set as to exactly where to clear mines and UXO in a given year. "The more demining [in those hazardous areas], the fewer the accidents—which is good."

The Remnants of War

Approximately 15,000 to 20,000 people worldwide die or receive injuries from land mines or UXO per year, according to the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS). The United Nations estimates that about 110 million antipersonnel mines lie scattered across more than 70 countries including Afghanistan, Albania, Angola, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Nepal, Lebanon, Somalia, Sudan, Mozambique, Vietnam, and Laos. However, the UNMAS describes Cambodia as "one of the most heavily contaminated nations in the world," a country "littered" with land mines and UXO that remain a legacy of 35 years of conflicts. The Cambodian Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority (CMAA), which coordinates demining operations in the nation, reports more than 60,000 deaths and injuries from land mines and UXO between 1979 and 2004 and 1,675 casualties 2005-2007.

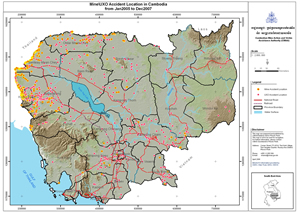

The red marks encircled in yellow indicate land mine accident locations and the red marks encircled in pink show where UXO accidents have occurred in Cambodia. Image courtesy of the CMAA. |

Currently, Engeset is working with In Channa, manager of the CMAA's Database Unit (DBU), to quality assure and analyze thousands of pieces of mine data to get the best possible picture of where the worst problems with mines and UXO exist. They're using GIS software from Esri to build the database and produce the maps and charts that will help policy makers prioritize the areas that need to be demined.

The maps, authored using ArcView from the ArcGIS Desktop software suite, starkly highlight where the most antipersonnel mine accidents have occurred: Battambang, Banteay Mean Chey, Otdar Mean Chey, Siem Reap, and Preah Vihear provinces in northwestern Cambodia. That was where many antipersonnel mines were laid during a long conflict that involved the Khmer Rouge, the Vietnamese, and other factions in a civil war. Maps also show that cluster munitions accidents are more prevalent in the eastern provinces bordering Vietnam, where the United States conducted bombing runs during the Vietnam War.

Why set priorities on when and where to demine? Engeset says that clearing land ad hoc—without concrete evidence of a hazard—would perhaps mean spending money where it's not needed and leaving dangerous areas uncleared.

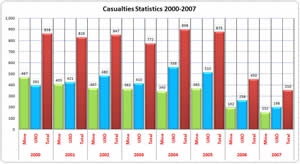

This graph shows the number of people killed or injured in land mine and UXO accidents in Cambodia since 2002. Image courtesy of the CMAA. |

"Demining is quite easy in the areas where there are no mines," she said. "If you don't have the prioritizing data, how do you do the work? Where do you start? You will waste time, lives, and money." Engeset believes the work being done using GIS is now paying off. "By setting priorities and targeting the heavily mined locations, some of the most dangerous areas have been cleared," she said.

Casualties from mine and UXO accidents plunged 60 percent during a recent two-year period, falling from 875 deaths and injuries in 2005 to 350 deaths and injuries in 2007. "Time and the elements, such as rain, also are taking a toll on the mines and UXO, causing them to detonate less often and helping lower the casualty rate," Engeset said.

Extension Needed for Mine Clearance

In 1997, Cambodia signed the Ottawa Convention (also known as the Mine Ban Treaty), which bans the production and calls for the destruction of antipersonnel land mines. A provision stipulates that signators must clear their countries of all known land mines within 10 years. Cambodia's deadline will be in 2009.

A Cambodian woman and her father each lost a foot in a land mine explosion that occurred in a rice paddy. Courtesy of the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC). |

Last January, Engeset took a leave from her job at Geodata AS, the Esri distributor in Norway, to join NPA and go to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, to serve as a technical advisor for the CMAA's national database project, which is funded by the U.S. Department of State and the Norwegian government's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She's helping the CMAA consolidate and improve the quality and usability of the data. The current focus is on the extension request to that provision in the Ottawa Convention. She and Channa and his team collect and quality assure the data, which they will then analyze to answer two major questions: What areas are left that definitely need to be demined? And how long might that work take? The results of the analysis, in the form of maps and statistics, will be part of the request to ask for additional time to complete clearing the mines.

"We are preparing an extension request for having 10 more years to do this work," Engeset explained. "There are a lot of areas where we know we still have land mines."

The deadline to prepare and quality assure the data will be August 2008, then the analysis work, using ArcView, will begin.

Community based-demining workers conduct a sweep for mines in Ta Saen commune, Kamrieng district, Battambang province, Cambodia. Photo courtesy of the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC). |

This is a complex project for many reasons. Engeset and the CMAA work closely with the Cambodian Mine Action Centre (CMAC), which conducts about half the demining operations in the country. (The two other major organizations are the Mines Advisory Group [MAG] and Halo Trust.) For the extension request, the CMAA must make sure that the data (e.g., shapefiles that show the location of hazardous mined areas) from technical surveys conducted by CMAC and entered into CMAC's five provincial databases matches up with the information in the CMAA's database. "MAG and Halo Trust also provide data to CMAA using Esri's ArcGIS software," Engeset said.

Besides the results of technical surveys, the CMAA's database also contains the results of the National Level One Survey conducted in 2001 and 2002 in 13,908 villages in Cambodia, a country 181,040 square kilometers in size. During the survey, information was collected about accidents and suspected locations of land mines and UXO based on interviews with villagers.

According to the UNMAS:

- 6,422 villages were identified as contaminated with land mines or UXO to some extent. "About 5.1 million people in or around those villages are considered at risk," said Engeset.

- 7,486 villages were identified as uncontaminated.

- 20 percent of all villages in the country are contaminated to the extent of having an adverse socioeconomic impact on the people.

Equipped with the results of the National Level One Survey, CMAC is returning to the 6,422 contaminated villages (except those already demined) to conduct technical surveys and map the exact locations of the hazards. CMAC operators use explosives-sniffing dogs and handheld mine detection equipment to locate the mines. "If they find the mines, they use GPS to map the border of the areas," Engeset said. That information is stored as polygons with ArcGIS Desktop and later converted into shapefiles that, along with other data, can be shared and analyzed.

"Right now, we are working very hard with the operators to be sure we have the same information that they have stored in their databases," Engeset said. "As soon as we have all the data stored in one place, it's easier to analyze."

The analysis will start this fall and continue through 2008.

Resolve for Solving a Problem

"As Cambodia's population increases, people are on the move looking for land to open up to farming and industry, making mine clearance all the more pressing," Engeset said. Some people continue to live in the middle of minefields and go out into the fields daily, risking their lives. She's pleased to help make their futures safer.

The CMMA Database Unit in Phnom Penh includes (in the back row from the right) In Channa, Tatn Sara, Ros Sophal, Yech ChivLeng, and Eang Kamarang and (in the front row from the right) Meng Thary, Teang Ratha, and Arleen Engeset. Another team member, Hy Bunhok, is not pictured. |

"I am not an expert on mines, but I do know about the information systems," Engeset said. "This problem is huge in Asia, and when you meet the victims, it affects you."

She's constantly amazed by the tenacity of the people who continue to work in dangerous conditions. Engeset still remembers a tenacious Thai farmer who survived two land mine explosions.

Though his right foot was blown apart when he stepped on an antipersonnel mine, the farmer refused to let the accident prevent him from pursuing his livelihood and feeding his family. Fitted with an artificial limb, he returned to work in the rice fields where he had tripped the mine.

The man duly noted his accident during a Level One land mine/UXO survey that Engeset worked on during an NPA project in Thailand. And the story would have ended there, except that Engeset and her colleagues noted a discrepancy in his report. The man had filed two forms listing two locations in the rice paddy for where the accident occurred. Thinking he had made an error, they sought out the farmer and were shocked to learn he had stepped on two mines at two different times.

But the farmer, good humor intact, counted himself fortunate because he was struck in the same foot twice. Recalled Engeset, "He said, 'Actually, I was quite lucky. The second time, I had my artificial leg on, so that was okay.' "

For more information about NPA or the CMAA, contact Arleen Engeset at arleen@npaid.org.kh.