ArcWatch: Your e-Magazine for GIS News, Views, and Insights

September 2011

Visualizing Ancient Hopi Villages with ArcGIS Explorer

3D Application Connects Hopi Youth to Their Heritage

Making connections to the past is one of the primary missions of archaeologists.

Specializing in the Hopi culture of northern Arizona, University of Redlands associate professor of archaeology Wes Bernardini advocates an interactive approach to archaeological research that encourages students to learn about the past through exploration and discovery. When representatives from the Hopi Tribe approached Bernardini for help in igniting younger Hopis' interest in their heritage, Bernardini knew that an interactive 3D GIS tool would be a great starting point.

Communicating with Maps

With a grant from the Keck Foundation, Bernardini developed a dynamic application to kick-start conversation between the generations. Called the Hopi Landscape Portal, the application uses Esri's ArcGIS Explorer Desktop to create an interactive experience that enables students to virtually tour Hopi villages circa 1000 AD and learn about their ancestors' way of life.

In 1998, Bernardini began to record ancestral Hopi villages as part of a project to study migration and demography in the prehistoric American Southwest. During the course of Bernardini's work recording the locations of the villages, ArcGIS became his primary tool for storing and creating both 2D and 3D maps of the site locations. These maps—especially the 3D reconstructions and animations he made in ArcScene and ArcGIS Explorer—became the principal way he communicated his work to the tribe. Over time, his Hopi colleagues became increasingly interested in the potential of geospatial technology to tell the story of the tribe's history.

Empirical Value of Folklore

Bernardini says that from the 1950s into the 1980s, anthropological science went through a regrettable period of isolation from the tribes its practitioners studied. "Many anthropologists at the time decided that indigenous oral traditions weren't empirical enough, meaning the traditions did not rely on data gained by hard-nosed research," he says. "They decided that these stories had no scientific value and turned away from the tribes as a source of information."

Fortunately, Bernardini started his career when archaeological practice was coming around to a more collaborative methodology. Thanks in part to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), a federal law that formally gave tribes in the United States a role in controlling archaeological sites on federal land, archaeologists began interacting with tribes again.

"We quickly learned that tribes held important information about the past that we had been missing," says Bernardini. "Stories about ancient migrations and conflicts often lined up with archaeological reconstructions or suggested different explanations for past behavior that drove new research."

As Bernardini's relationship with the Hopis developed, the older tribe members voiced their concerns about sustaining their culture into the next generation. "The elders saw that many kids were disassociated from their heritage and asked me for help in sparking their interest with these maps," said Bernardini. "I knew that whatever we did, it had to be more nuanced than just throwing tons of information at the kids." Ultimately, they wanted something that would encourage the children to have a genuine interest in learning more from the elders themselves. "We needed something that would start a conversation between the generations—more of a catalyst than a comprehensive lesson plan," Bernardini says.

Hopi Landscape Portal

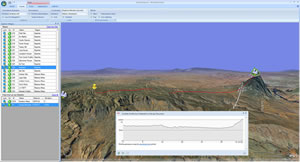

To start, Bernardini input archaeological sites thought to be ancestral to the Hopi tribe into ArcGIS Explorer Desktop and made some quick tools with Python to simplify the user interface. A tabular tool that gave users the ability to query based on location and chronology would be the application's launching point. The tool consists of two table interfaces: The first shows a list of the ancestral sites that can be sorted by site name, region, date the village was established, or date the village was no longer occupied, viewable by clicking on the column header. Using the second table interface, students can bracket a time period (e.g., start > 1300 AD and end < 1500 AD). Children could quickly call up sites from a particular area and/or time period of the Southwest, then quickly jump to those areas in a 3D fly-through.

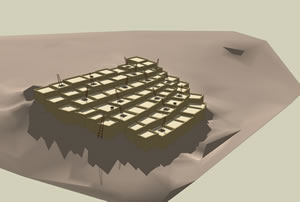

"When we first tested it in Hopi schools, kids almost always started at their current village, because that's what they know best, and began to venture out from there," says Bernardini. "Each time they jumped, they landed on a 3D reconstruction of the village [constructed from extruded polygons] and a clickable link to basic information about the footprint [i.e., the number of rooms present at the village, which is a measure of the number of people who lived there] and occupation dates of the site, as well as photographs taken during mapping fieldwork."

Bernardini saw 3D GIS tools like ArcGIS Explorer as way of capturing the attention of the kids, who devote a lot of time to watching ESPN and playing video games. Being typical Westernized youth, some Hopi children understandably had more interest in Phoenix Suns basketball games than ancient sun calendars.

Besides representing ancient dwellings, Bernardini also wanted to bring to life part of the landscape that informed Hopi cosmology. "Hopis have a very intimate understanding of the horizon; mountains that mark cardinal directions and the residences of deities or dates on the solar calendar—all of them are culturally meaningful places," says Bernardini.

A polygon shows the extent of the visible horizon from the village of Walpi, northeast of Flagstaff, Arizona.

Each village in the Hopi Landscape Portal also links to a table containing line-of-sight information to more than 20,000 mountains across Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. When a student jumps to a village, a table of the visible peaks appears ranked in order of their topographic prominence. Clicking a peak calls up another custom query tool that generates a list of other ancestral villages that can also see that peak. "We wanted the tool to help students see places that anchored the visual landscape and captivated the ancient Hopi imagination."

The Hopi Landscape Portal exemplifies the collaborative approach to research that has greatly benefited both Hopi archaeology and the tribal members themselves. "Every time I work directly with the Hopi, we both get something new out of it," says Bernardini. "We add new information about ancestral places, allowing us to build an even richer picture of the Hopi past." In the course of that documentation, Bernardini fills more gaps in his research about migration patterns and localities the tribe once settled in, gradually refining the portal for the next generation's benefit.