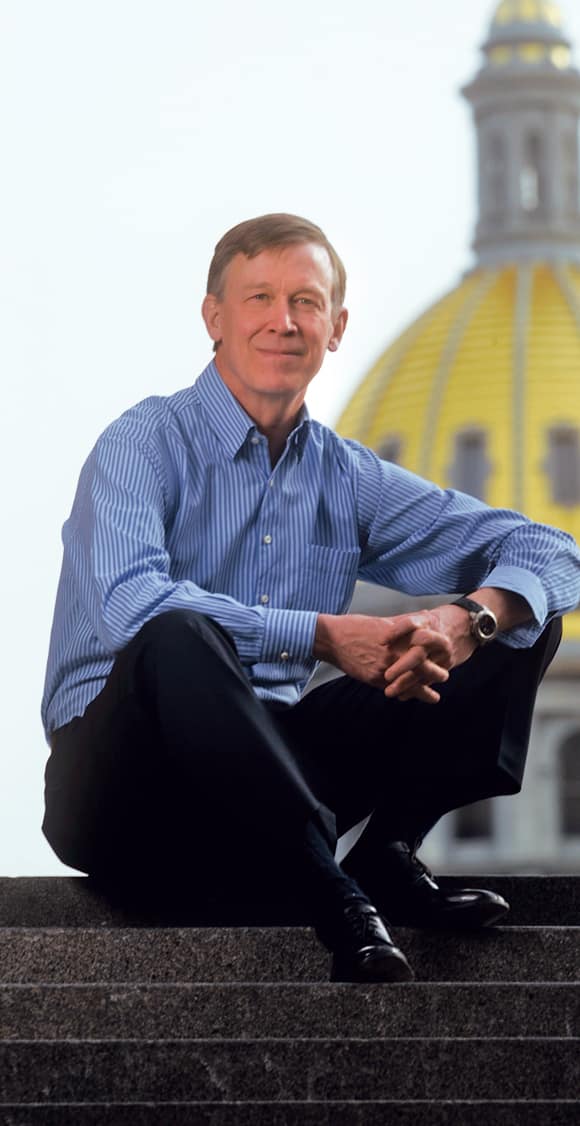

For his entire career in public service, Colorado governor John Hickenlooper has been following a passion for integrating geographic knowledge into government.

“I get a chance to meet with a lot of leaders around the world, and it’s my experience that Governor Hickenlooper is one of those very special people who understands the power of geography and how to apply it,” Esri president Jack Dangermond said at the Plenary Session of the 2018 Esri User Conference (Esri UC).

Dangermond presented Hickenlooper with Esri’s Leadership in Government Award, which is reserved for geospatial pioneers at the local, state, and federal government levels who encourage the use of GIS not only for everyday operations but also for developing enduring innovations.

“He has a unique talent for leading, and he connects people using rational thinking and science-based approaches,” Dangermond observed.

This is exactly how writer and journalist James Fallows characterized Hickenlooper when introducing him at the Esri UC’s concurrent Senior Executive Summit, where Hickenlooper gave an engaging speech about how GIS has been instrumental in leading the State of Colorado out of some difficult circumstances and spearheading a number of remarkable accomplishments.

“I think you can think of him as part of [a] movement that can save America,” Fallows recounted to attendees. “For the foreseeable future, the national level of politics in the United States and a number of other democracies, too, seems to be a zero-sum contestation: in order for me to win, you have to lose.”

But at the local, regional, and state levels, there’s a very different spirit, argued Fallows, with people emphasizing practical compromise, positive achievement, and win-win solutions that can help these areas develop successfully in the long run.

“I contend that the next wave of leadership in the United States will be somebody from that tradition…somebody that has made his or her reputation bringing people together, being able to do things that build popularity and prosperity and comity and inclusion, and all the other things we would like to think Western democracy and the United States are for,” said Fallows. “We don’t know where this next wave of leadership will come from, but…there are many, many examples across the country, of whom Governor Hickenlooper—now ending his successful second term as governor of Colorado—is an illustration.”

A Spatial Thinker, Always

Hickenlooper has a profound understanding of the power of data and mapping to inform decision-making, business, and policy.

He is reportedly the only practicing geologist to ever become a practicing governor in the history of the United States. And according to Fallows, he is only the second ever beer brewer to hold the position; Samuel Adams was first as governor of Massachusetts in the late nineteenth century.

In all phases of his career—from working as a petroleum geologist to opening a string of brewpubs and restaurants to being mayor of Denver and eventually governor of Colorado—maps have been crucial to Hickenlooper’s success.

When he was a master’s student in geology at Wesleyan University in Connecticut in the late 1970s, he lived and died by maps, he said.

“That was actually when GIS was paper maps,” Hickenlooper recalled during a recent phone interview. “We would use transparencies to overlay different rock formations on our maps, which is in essence what we learned to do when GIS actually came into being as a technology. It took us forever—days—to make those transparencies line up properly and transfer information. Now, you can cross-coordinate information and line up data with the flip of a finger.”

Hickenlooper eventually got a job as a geologist for Buckhorn Petroleum in Colorado. But during the oil bust of the 1980s, he got laid off—along with pretty much every other petroleum geologist.

So he and some friends decided to open a brewpub in Denver’s then-derelict lower downtown. Hickenlooper wanted the bar top of their new Wynkoop Brewing Company to be a map, or at least a representation of one. A friend concocted a fictitious place, and they built a map of it into the bar top with concrete, copper, and shale—a callback to Hickenlooper’s geology days.

“We got more comments on that because people thought it was a real place,” he told the summit audience.

Building on the success of their first venture, Hickenlooper and his business partners opened more than a dozen brewpubs and restaurants across the Midwest.

At the same time, Hickenlooper became somewhat of a staple in the Denver community—no doubt in part because Wynkoop was eventually credited with influencing the revitalization of Denver’s lower downtown, which is now home to popular restaurants, shops, and nightlife. (The addition of Coors Field, where the Colorado Rockies baseball team plays, didn’t hurt, either.) So he decided to run for mayor. And in his first ever political contest, he won.

Given his background in geology and business, it was natural for him to use GIS to help run the city better, according to Esri government strategist Pat Cummens.

“He’s always been a spatial thinker,” she said. “He knows the value of data and that you need data to drive good decision-making.”

During his eight years as mayor of Denver, Hickenlooper’s administration used GIS to map all the trees in the city to ensure diversity in the canopy, find sources of pollution in the Platte River, work out where kids were suffering from lead poisoning, and more.

In 2011, he was elected governor of Colorado, and his penchant for GIS didn’t fade. It shows no signs of waning now, either, even with his time in the governor’s office coming to a close.

“For so many of the challenges of modern life, GIS is the last great hope,” he said. “It’s not the solution to everything, but I think, in a funny way, it’s a partial solution to almost everything. One of the challenges we face is how rapidly the world is changing, whether you’re talking about natural disasters and hundreds of thousands of people being displaced or you’re talking about how pollution works and how we can clean the air and the water. Those solutions are all going to come down to our ability to use GIS effectively. The patterns of drought and therefore wildfires and therefore floods, medical epidemics, public health issues around nutrition and the spread of virus—all these things are very, very complex challenges that demand GIS responses.”

Over the last eight years, Hickenlooper and his administration have employed GIS to come up with solutions for all these problems and more. In 2012, when Colorado experienced drought that led to some of the worst wildfires in the state’s history, the government used GIS to map the fires and predict where they were going to go so it could better allocate its resources. When that wildfire season ushered in ruinous flash floods the following year, the government used GIS again to map and redesign highway contours and prompt all the repair crews to collaborate. Not only did this allow evacuated residents to return to their homes much quicker than initially thought, but it also helped the state rebuild those highways so they were stronger, safer, and more resilient.

“When people have lost everything…you can’t come and say, ‘Well, we’re going to build it back,’” said Hickenlooper. “You’ve got to come back and say, ‘We’re going to build it better.’”

Having accurate data and being able to map it dynamically is a big part of that.

A New Golden Age

Hickenlooper believes that we now live in the golden age of data, which is also the golden age of maps. This is because, while maps of the past were made of what already existed (the landscape, animal tracks) and eventually became records of what we created ourselves (roads, bridges), they can now show what we hope to build (cities with clean air, rural communities with strong economies). Essentially, modern-day maps can illustrate the future.

“This is a moment that is going to have unbelievable transformational capacity, not just for elected leaders but [also] for businesses [and] nonprofits,” he told the audience at the summit. “Maps…are a powerful tool by which people work together and collaborate—another natural resource that we seem to have in short supply.”

But with leaders like Hickenlooper, maybe this kind of data-driven collaboration is about to arrive at its golden age, too.