Felix Finkbeiner Sees the Forest and the Trees: 4.2 Trillion of Them

Felix Finkbeiner is out to save the world, one tree at a time.

At age 9, Finkbeiner famously launched Plant-for-the-Planet, which initially aimed to plant 1 million trees in every country in the world. While that seemed like a tall order for the boy and a group of his classmates in Germany, the idea took root, and they rallied youth and adults behind this effort to plant trees to reduce the harmful effects of high carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere.

At age 20, Finkbeiner was standing onstage at the Plenary Session of the 2018 Esri User Conference (Esri UC) in July with a new message: Help plant or donate toward planting 1 trillion more trees using a new app that the Plant-for-the-Planet launched that day.

“If you want to help us do this, it is very easy,” he said. “You take out your phone, you go to trilliontree.campaign.org…and then pledge how many trees you want to plant.”

Finkbeiner has been wildly successful leading the Billion Tree Campaign. With support from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), he has recruited thousands of young people and business, government, and environmental leaders to the cause. They’ve stepped up in a big way—with shovels or donations in hand—to plant close to 15.3 billion trees since 2007.

But Finkbeiner, who was raised in a small town in Bavaria, was never one to think small. The UNEP’s goal of planting 1 billion trees has long been surpassed. So in 2013, he asked Thomas Crowther from the Crowther Lab at ETH Zürich—a top science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) university in Europe—to research how many trees there were on the earth and how many more the planet could sustain.

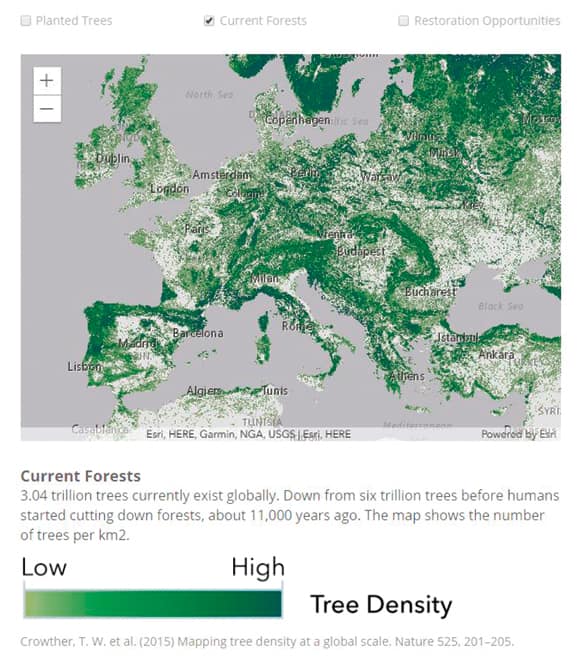

“[Crowther] came back to us [three years later] with two important answers,” Finkbeiner said. “The first one was that 3 trillion trees already exist. And the second one is that we can restore another 1 trillion trees.”

The earth, it turned out, can maintain 4.2 trillion trees. “So we knew what the next step had to be,” Finkbeiner said. “We had to transform the Billion Tree Campaign into the Trillion Tree Campaign.”

What better way to get youth and many adults, who are highly attached to their smartphones, interested in planting trees than to roll out a Trillion Tree Campaign app with a map that tracks where people or organizations plant their trees? And what better place to launch the app than the Esri UC Plenary Session, with its environmentally conscious audience?

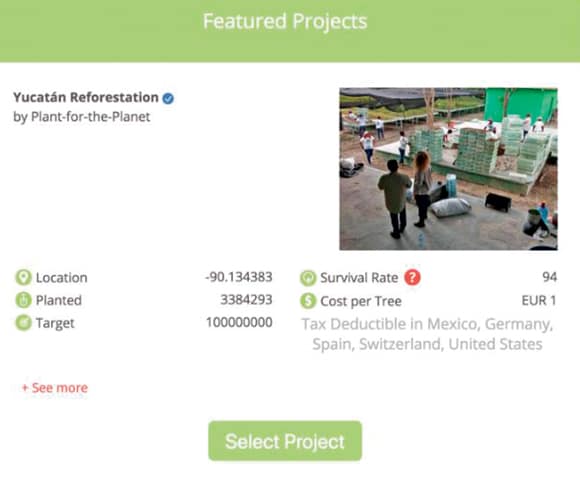

Finkbeiner said the Plant-for-the-Planet initiative, which acquired 55,598 acres on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, hopes to plant 100 million trees there by 2030.

“But to reach our goal of [planting] a trillion trees, we need to do much more,” he told the crowd. “We need to get millions of people all across the world to help us in planting trees. But how? What we need to do is make it as easy and as fun as possible for anyone to get engaged and plant trees. To do that, we built an app.”

This companion app is an integral part of the Trillion Tree Campaign, giving anyone in the world with Internet access the ability to register, document, and map each tree they plant, as well as view where others are planting trees.

Finkbeiner demonstrated how to use the custom web app, built by his organization’s team of developers with assistance from Esri using ArcGIS API 4.x for JavaScript. (Plant-for-the-Planet also plans to release mobile apps for Android and iOS devices.)

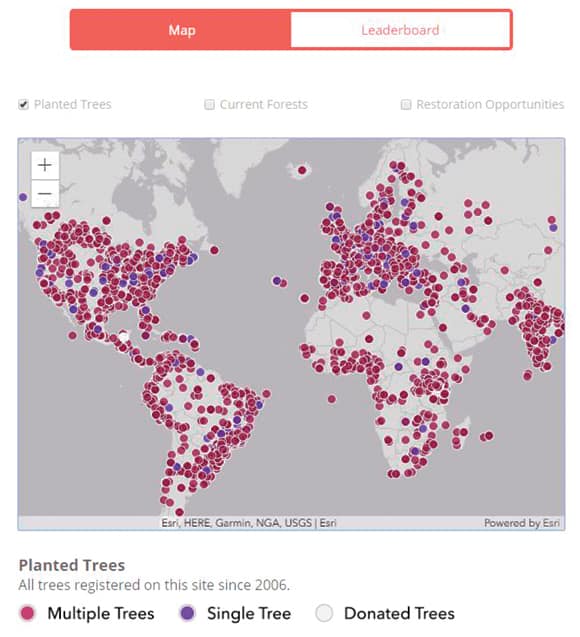

After signing in at trilliontreecampaign.org and clicking on Explore on the menu on the left, users see an embedded ArcGIS Online map that employs the World Light Gray Base map.

Users can mark a check box above the map to see various layers: where trees have been planted worldwide, who planted them, and how many they planted; where current forests exist; and areas where forests can be restored. According to a leaderboard in the app, most of the trees have been planted in China, India, Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Mexico.

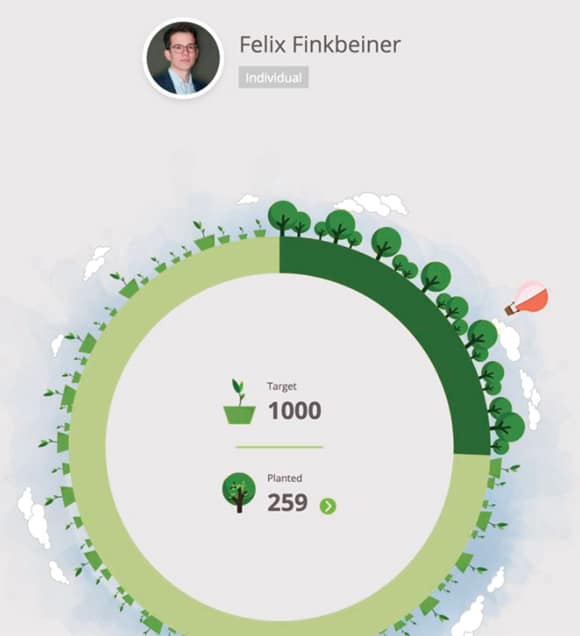

Finkbeiner also showed the audience how to use the app to create a personal profile and sign up to plant trees. People can set a target number of trees to plant, register a planted tree, then document and map it.

“I can register the trees I’ve planted, [listing] the exact species, the exact location, and if I want to, I can also add pictures of my tree and measurements,” Finkbeiner said.

The app allows people to donate money to a tree planting project as well.

“And for each project, you can see where they plant,” Finkbeiner said. “You can see pictures and videos of the project and the survival rates of the trees planted and the cost per tree.”

Finkbeiner encouraged the audience to pull out their phones and sign up.

“I’m really excited to see how many trees we can plant together,” he said.

Influenced by Wangari Maathai

How did a young boy get so enamored of tree planting that he grew up to become an influential voice in the environmental movement, speaking, for example, to the UN General Assembly?

The journey began in 2007 when Finkbeiner’s fourth-grade teacher had him give a presentation on climate change. At that age, Finkbeiner worried about saving polar bears from global warming.

“When I was five years old, I got this huge polar bear [stuffed animal] as a gift from my aunt. [The toy] was bigger than I was at the time,” he recalled. “It was my favorite animal. I found out that the polar bear was in danger, so I really wanted to save the polar bear. That was my motivation back then.”

Finkbeiner also read about Nobel Peace Prize winner and environmental activist Wangari Maathai, the founder of the Green Belt Movement, a well-known tree planting campaign that started in the 1970s. The goal of her campaign was to plant 30 million trees to counter deforestation, mainly in Africa, and give women, who did most of the tree planting, an income. Maathai died in 2011.

“Back then, I didn’t understand the real depth of what she did,” Finkbeiner reflected during an interview at the Esri UC. “I just understood she was planting trees, and [that] it was one of the best and easier things we can do in terms of fighting the climate crisis. But as I became older and the more I learned about her, [I realized] that’s not even the tip of the iceberg. How she used tree planting for women’s empowerment was absolutely fantastic, [and] how she was able to combine environmental with social progress was great.”

Ironically, the same year Finkbeiner gave his talk in school, Maathai gave a powerful keynote about tree planting, poverty, women’s entrepreneurship, and environmental sustainability at the Esri UC. (Read her story in the July 2007 issue of ArcWatch.)

“She was amazing. […] She inspired many of us and still does,” said Esri president Jack Dangermond this year before introducing Finkbeiner. “She also inspired [this] young man, who I met when he was about 10 years old. He was just full of excitement about Wangari…and he said, ‘I am going to get kids to plant a million trees in every country!’”

Dangermond didn’t quite believe that Finkbeiner could accomplish that. “But then he did it,” Dangermond remarked.

Finkbeiner recalled the enthusiasm that Maathai’s story stirred in him (they eventually met), inspiring him to want to help her in any way he could.

“I told my classmates that we should plant 1 million trees in each country of the world,” he said. “Many of my classmates loved the idea, even though I think none of us knew how much a million was or even how many countries existed in the world.”

His worries about the polar bear expanded to humankind.

“Soon after, we understood that this was not really [only] about saving the polar bear,” Finkbeiner said. “This is about our future. We will be the ones suffering from the consequences of the climate crisis.”

The Fight for Climate Justice

In 2011, the UNEP handed over the reins of its Billion Tree Campaign to Plant-for-the-Planet. Since then, Finkbeiner has recruited more than 67,000 children around the world as climate justice ambassadors, planting trees and giving talks at schools and organizations in their communities.

Finkbeiner recently earned a bachelor of arts degree in international relations from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) at the University of London. When he’s not studying, researching, swimming, or snowboarding, he crisscrosses the globe, calling for climate justice. He says tree planting is one means of reducing the CO2 levels in the atmosphere and mitigating climate change.

Before embarking on the Plant-for-the-Planet mission, he really wasn’t a tree guy. The first tree he ever planted was on March 28, 2007, shortly after he made his class presentation on the climate crisis. Yes, he remembers the exact date.

“It was a big moment,” Finkbeiner said, chuckling. “It was a [crab] apple tree at the entrance to my school, so I walked past it for the next 10 years.”

And how is it doing?

“It’s growing,” Finkbeiner said, estimating that the tree had doubled in size in 11 years. He said its growth rate is slow compared to the trees his organization plants in the Yucatán Peninsula.

“It was not the most beautiful of trees,” he admits. “If we would have known this was going to turn into a proper organization, we would have planted an impressive tree.”

It might surprise some people, but Finkbeiner doesn’t have a favorite tree. For him, it’s more about what trees can do holistically for the planet.

“It doesn’t matter why you plant the tree, it will still…absorb [about] 10 kilos [22 pounds] of CO2 each year,” said Finkbeiner, who has become more fascinated by the science of trees.

The Crowther Lab is helping Plant-for-the-Planet determine what species of trees need to be planted and where they are likely to grow successfully.

“It’s not just about how many trees we plant, but it’s [also] about planting these trees well,” Finkbeiner said.

Crowther, who spoke at the Esri UC as well, said that only about 30 percent of trees planted in tropical areas around the world grow to maturity.

“What [forest] restoration projects need…is information about which species to restore, which soils can support them, and what the ecological consequences will be,” he said.

Finkbeiner offered some tree planting tips to individuals and organizations that want to join the Trillion Tree Campaign.

- Seek advice from a local forester to find out which species will grow well in specific areas.

- When planting trees at a large scale, plant a variety of species rather than monocultures.

- Take care of the trees after you plant them, making sure they have enough sunlight.

And Finkbeiner wants to learn more about trees. Next, he will pursue a PhD in forest ecology from ETH Zürich. He plans to learn how to use ArcGIS technology at the Crowther Lab to find out, essentially, how to make the Trillion Tree Campaign a lasting success.

“There are still so many unanswered questions in [relation to] global forest restoration,” said Finkbeiner. “We have to improve the maps of where we can restore forests and develop better maps regarding where we should prioritize [tree planting]. And we need to model what impact this forest restoration would have on climate change in terms of how much carbon these forests will compute over the next [several] decades.”

Finkbeiner’s Trillion Tree Campaign presentation inspired many people in the Plenary Session audience, including 16-year-old Zachary Linton of Lander, Wyoming, who recently learned how to use ArcGIS and is mapping the movement of a herd of bighorn sheep in his state. He hopes his project will ultimately help to restore the population of bighorn sheep in Wyoming.

“There is a lot of opportunity in the GIS world,” said Linton. “Young people can really make a difference, like Felix Finkbeiner and his Trillion Tree Campaign. It gives me hope that someday I might make a difference in the world with one of my projects.”