Gabriel Ortiz has devoted his life to geography, and he’s always been fascinated by technology.

“I’ll never forget the day I touched a computer for the first time,” he said, reminiscing about being a student at the University of Cantabria in Spain. “It really changed my life.”

Drawn to that fascinating point that many in the GIS world know so well—where art and science meet in cartography—he studied geography. He was enthralled when, as a student in the mid-1990s, he combined 3D models and imaging to build an animated digital terrain for the first time. He dove headfirst into learning ARC/INFO, never shying away from trying the latest technology and always keeping an eye on what was coming next.

From then on, Ortiz has been driven by a deep-seated passion for his profession, which he finds fun and challenging, and for public service.

“I’m attracted to solving problems and thinking about creative ideas that I can try,” he said. “I find energy to do all of this because I am serving a bigger purpose, which is creating a better society.”

Innovating at New Scales

As the head of cartography and GIS services for the government of Cantabria—a 2,100-square-mile swath of mountains and beaches in northern Spain—Ortiz and his team of five have spearheaded ways of using GIS with AI and 3D modeling at scale. They’re employing computer vision trained on decades of aerial photos to see what others can’t: which beaches will overflow on summer weekends, or where forestland has doubled over the last 60 years.

The team is also building a digital twin of the whole region, which Ortiz believes will help project Cantabria’s rich archival data into the future, giving three-dimensional insight into planning future transportation systems, how first responders approach emergency situations, and more.

“We are constantly using AI to make society aware of the problems and why those problems happen,” Ortiz said. “And I am totally invested in the idea of bringing live data to the digital twin—starting the journey to the next evolution of cartography and GIS.”

Too Many Beachgoers, Too Little Beach

Following the COVID-19 pandemic, when people became more conscientious about space constraints, the government of Cantabria wanted to investigate overcrowding on beaches. Ortiz’s bosses asked him to make some maps. He counted people instead.

Training AI to detect beachgoers in aerial photos was difficult. People appear as faint shadows, barely distinguishable from towels and umbrellas. His team labeled images and taught the model to recognize patterns across five aerial surveys from 2002 to 2017.

The results changed beach management in Cantabria. On sunny summer holidays, about 76,000 people visit the area’s 104 beaches, but the distribution is uneven. Eastern beaches attract the heaviest crowds, while western beaches offer similar beauty with far fewer people.

Pressure maps encourage visitors to make smarter choices. Small popular beaches face the greatest stress: A tiny beach packed with people suffers more damage per square meter than a large beach with double the crowds.

The model assigns weights to usable beach area: Dry sand counts fully, wet sand counts at 50 percent, dune systems count at 10 percent, and rocky areas count at 5 percent. This reveals environmental pressure per square meter, based on each beach’s composition.

Beyond counting beachgoers, the team also analyzes where vehicles cluster—often in sensitive coastal areas—to identify where better public transit could reduce damage. Ortiz’s vehicle detection models reveal clear patterns: hundreds of cars parked in grasslands, and campers in areas never meant for them.

The maps suggest solutions. By pinpointing popular spots and transport bottlenecks, officials can plan new bus routes and better manage parking areas to serve visitors while protecting the landscape.

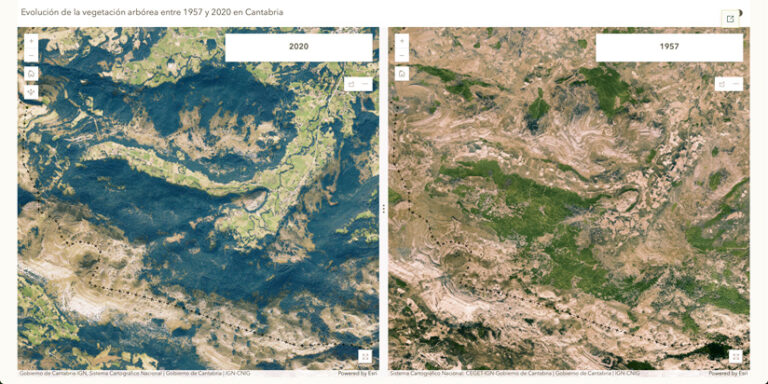

Imagery Shows an Anomaly: Forest Growth

The team’s most surprising discovery so far in using AI to analyze years of aerial footage is a welcome treat: Forest cover in Cantabria more than doubled between 1957 and 2020. Unlike global stories of deforestation, this region’s forests are recovering.

“This is not an opinion. This is what is really happening,” Ortiz said while highlighting yellow areas on maps that show vegetation gains far exceeding losses in red.

The change reflects social and economic shifts. As people abandoned farming and moved to cities, marginal agricultural lands reverted to forest. Industrial eucalyptus plantations expanded, but native species also thrived. The landscape is dramatically more forested than it was in the 1950s.

National officials confirmed that the findings match broader trends. The analysis shows that forests can recover when human pressure shifts—and underscores the urgency for managing that growth.

To that end, Ortiz has developed an innovative, AI-based system to automatically detect and monitor forest areas that are being logged. Moving from data to action, he expects that this will open up new possibilities for overseeing official permits.

Doing More with Less—for the People

Ortiz calls computer vision “a force multiplier” that lets his six-person team accomplish what would traditionally require dozens of specialists and millions of dollars.

“We will see smaller and smaller teams creating the most important value,” he predicted. “This is going to be the new normal.”

His team’s efficiency comes from choosing the right problems to solve with automation.

“Many people try to do crazy things with AI,” Ortiz said. “This technology is excellent, but it’s not suitable for all problems. Choosing the right one and choosing the right strategy is very important.”

Rather than automating everything, Ortiz’s team uses computer vision for tasks that would be impossible or infeasible for human observers to do. And above all, they are motivated by an ethos of public service, which shapes how they view data sharing. Unlike organizations that guard datasets, Cantabria makes everything open.

“This data belongs to the taxpayer. It’s not our information,” Ortiz said.

The team’s mobile mapping apps put decades of territorial analysis into residents’ hands. Since 2016, the apps have allowed residents to access datasets anywhere in the region. The team’s ArcGIS StoryMaps stories combine analysis with informative explanations.

“One image has much more power than a thousand words,” Ortiz said. “When you publish something meaningful in a story map, people can interact with all the data. You can really tell stories and connect with people through them.”

A New Way to Experience Cartography

The next project for Ortiz and his team is building digital twins that capture lifelike 3D replicas of the region.

“Digital twins are the next evolution in cartography,” Ortiz said. “For centuries, we have been using projections to simplify reality to a flat canvas, to a paper map. But as digital technology evolves, the world doesn’t need to be projected anymore. We are going to be able to reflect reality with less demanding abstractions. We will be able to create lifelike replicas of our world.”

Traditional maps require specialized knowledge to interpret. Digital twins let people explore their landscape naturally.

“When you see something in 3D, it’s easier to understand than seeing a technical map full of colors and symbologies,” Ortiz said.

This accessibility could transform how people participate in land use planning. As digital twins evolve, these tools could guide residents and visitors in real time—helping them find uncrowded coves and forest trails while protecting fragile places. Everyone could see Cantabria through the eyes of those who know it best, experiencing the landscape with less pressure and more wonder.