Brianne Gilbert has spent nearly all of 2025 living in spreadsheets and maps. There, she has cataloged thousands of requests from worried Southern California homeowners wondering whether their soil may be contaminated by what seeped into the ground after the devastating and deadly Palisades and Eaton wildfires in January. More than 16,000 buildings and vehicles—plus all the metals, toxins, and plastics they contained—were consumed by flames.

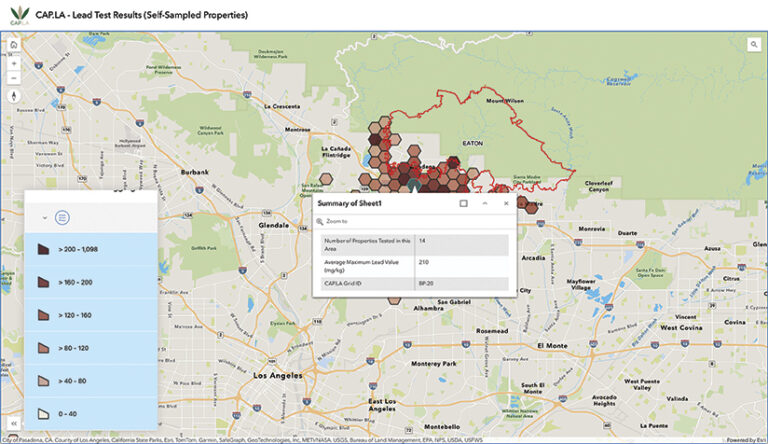

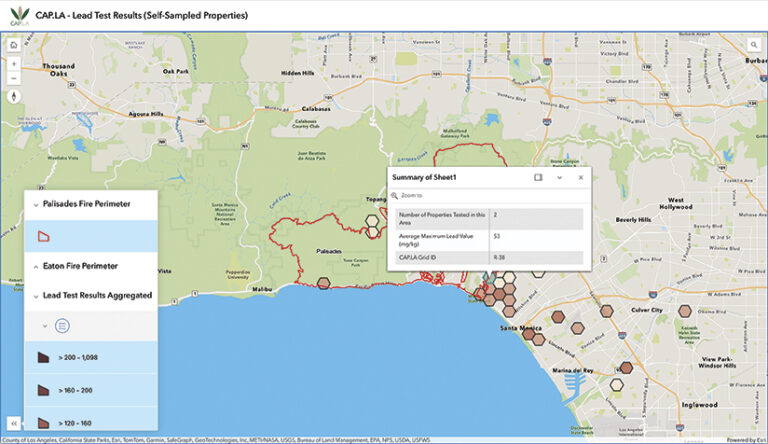

With funding from the R&S Kayne Foundation, Gilbert has been coordinating efforts by multiple universities through the Community Action Project LA, which aids those affected by the disaster in recovering. That includes helping to collect thousands of soil samples from neighborhood yards. Gilbert and her team have mapped the results using ArcGIS Online and ArcGIS Pro.

As managing director of the Center for the Study of Los Angeles (StudyLA), a research center at Loyola Marymount University, Gilbert normally oversees public opinion surveys, election exit polls, community studies, and outreach to tens of thousands of Los Angeles-area residents—much of it involving GIS. The center is experienced in budgeting for projects, assembling teams, and analyzing collected data. That’s why StudyLA was a natural choice when it came to reaching out to people affected by the fires.

In that work, Gilbert has also learned that a personal touch goes a long way. Homeowners not only sign up using an online form but also reach out directly via email and phone calls. She and her team have reviewed and responded to several thousand emails from homeowners with questions, concerns, and comments about the project.

“So much of it relies on trust,” Gilbert said.

Scraping and Testing Soil

Little has been normal about the wildfires that ravaged Pacific Palisades and Altadena. Despite their relative proximity, the two fires happened in areas with different governance structures. Only one—the Palisades Fire—happened inside the city of Los Angeles, overseen by the mayor. The other, the Eaton Fire, occurred within the purview of Los Angeles County’s board of supervisors.

The fires also raged in different geographic terrain, with winds carrying ash mostly out to the ocean in one and into neighborhoods in the other. But both fires left a hopscotch pattern of destruction. One surviving home could be surrounded by the ash of others that were razed.

In the several months since the fires, many affected homeowners have been weighing whether to return or rebuild. On top of needing to discard belongings that may have been engulfed or overwhelmed by smoke, they worry about what may have leeched into the ground. Private home insurance sometimes covers testing, but not always.

In other wildfires, federal agencies charged with removing hazardous debris might “scrape,” or remove, the top six inches of soil and test the earth below. Then, if needed, they would scrape more off the top and test again. They would continue until the soil was effectively in its pre-fire condition—not necessarily cleaner, but not more contaminated, Gilbert said. That’s what happened following the 2023 Maui Fire in Hawaii, for example.

For the Palisades and Eaton wildfires, the federal government did not test the soil and disposed of just the top six inches, saying that any soil contamination below that level was unrelated to the wildfires. Any additional scraping was considered “over excavation,” unnecessary, and costly, according to the US Army Corps of Engineers quoting the direction it received from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). As of early September, the US Army Corps of Engineers reported it had cleared debris from all affected lots that opted into debris removal—4,029 in Pacific Palisades and 5,642 in Altadena.

Without the intervention of Community Action Project LA, homeowners faced several thousands of dollars in costs to test their own soil to either confirm or calm their concerns.

A Need to See It on the Map

The small team at StudyLA working on this project sends messages to homeowners and maintains a database that records who had their soil tested, where, and when. When the results come in, StudyLA anonymizes, aggregates, and maps the data to preserve people’s privacy but also provide some clarity on the impact of the wildfires.

Protecting privacy has been a priority. The results of the testing that homeowners have requested go directly back to them and aren’t shared with anyone else, including government entities or insurers.

“We’re working for the homeowners,” Gilbert emphasized. “We’re doing something to help them right now, wherever they are with their situation.”

Gilbert has relied on ArcGIS to map soil testing, helping ensure that tests are distributed evenly across burn zones.

“I can’t imagine doing it without mapping,” she said. “I just need to see it on the map, and then I can move on from there.”

The StudyLA team uses ArcGIS Online to import the data from Microsoft Excel and map it on layers showing homes that remain standing, those that burned, and those that were affected but are located outside and adjacent to the burn zone. In ArcGIS Pro, the team overlaid the fire perimeter and measured a quarter mile around it.

Critical to Gilbert’s process has been the ability to seamlessly move between ArcGIS Online and ArcGIS Pro, particularly using the Update Data feature to see the latest view without going through a lengthy process each time.

“That’s huge,” she said.

Helping Homeowners

Soil testing could continue for the foreseeable future. Hypothetically, a homeowner with a home standing next to one that burned could get their soil tested and retested and even add a new layer of fresh topsoil. But a year later, if their neighbor begins rebuilding, the dust and dirt would get thrown up into the air again.

“The air doesn’t care where your property boundaries are,” Gilbert said.

She described this as the most meaningful project in her 17 years at the center. Among her many spreadsheets is a tab labeled “Kind Words.” It’s where she goes “if I’m having one of those ‘phew’ days,” she said, “when this project is so overwhelming and taking up so much mental capacity.” The tab has all the notes of thanks she’s gotten from homeowners—who are overwhelmed themselves—for the work her team is doing.