Communities across Alaska depend on maps of infrastructure and cultural data for everything from engineering and emergency response to resilience planning and grant applications. However, keeping these maps up-to-date can be challenging for some communities. And the maps are not always readily available in GIS formats.

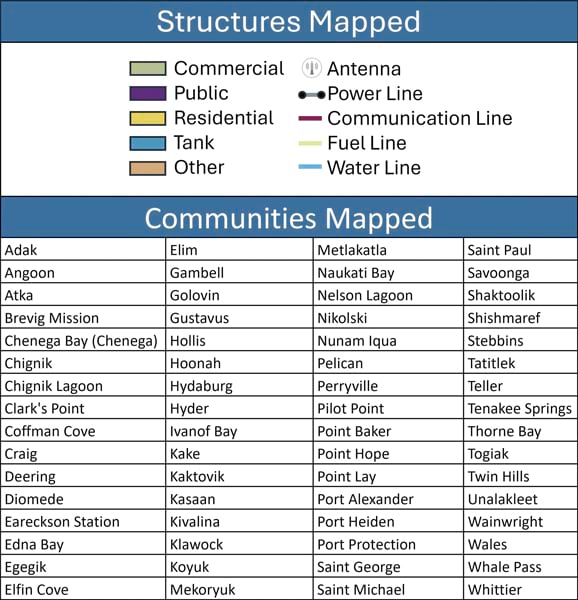

In 2023, Esri partner Dewberry, a privately held professional services firm, worked directly with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office of Coastal Management to scope out a large pilot project that would update community maps for 64 underresourced Alaskan communities. When bad weather heads for Alaska, NOAA frequently quantifies the storm systems’ predicted impact on the state’s remote coastal and riverine communities. Thus, resilience planning and emergency response largely drove the requirements for this project.

A year into it, the team from Dewberry reached out to Esri with an opportunity to collaborate. The team was interested in using content from ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World—including ready-to-use content and geospatial AI capabilities that automatically extract information from imagery—to build an updated GIS database and maps for the 64 communities. Maps would include information such as utilities, infrastructure, landownership, cultural resources, and harvest areas.

“In Alaska, we’re often working to bridge a significant data gap, especially in remote and underserved communities,” said Hillary Palmer, program manager for Dewberry. “This project provided an opportunity to build a strong foundation of infrastructure while combining local knowledge, emerging technology, and thoughtful cartography.”

A Wide-Ranging Project Steeped in Collaboration

The 64 communities selected for the project are small, remote, and economically disadvantaged and had some of the most outdated maps and data in the state. Most of these communities are located in what’s called the Unorganized Borough—portions of Alaska, comprising nearly half of the state’s landmass, that lack centralized municipal governments. (A borough in Alaska is what other US states typically call a county.) The Unorganized Borough presents challenges in terms of governance, infrastructure development, and resource allocation.

Prior to this project, many of these communities used AutoCAD maps. While these maps were a great resource, they had some limitations. NOAA wanted to not only provide data updates for these communities but also modernize the delivery of geospatial information. Additionally, NOAA sought to expand the usefulness of the updated data by creating and providing geospatial content across a variety of themes, including utilities and infrastructure.

Planning for the project involved coordinating closely with stakeholders, including the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium, and the Alaska Division of Community and Regional Affairs. Dewberry also leveraged the services of a tribal liaison to support engagement with local communities and help validate data, including in areas of cultural significance and where land is used for subsistence.

A Well-Timed Opportunity to Explore Geospatial AI

Imagery serves as a vital source for extracting a wealth of geospatial information and is an invaluable resource for mapping and analysis. Acquiring high-resolution aerial and satellite imagery is not always feasible, however, given time and budgetary constraints. Furthermore, visually inspecting and hand-digitizing features from imagery can be time-consuming and expensive.

Geospatial AI and deep learning can help save time and money by automating manual processes related to imagery. But not everyone has the expertise or resources to create such tools or train deep learning models. Leveraging ready-to-use imagery sources and capabilities to automate the extraction of geospatial information is an appealing option for many organizations.

ArcGIS Living Atlas provides a wide range of ready-to-use content in a variety of modalities. This includes maps, apps, layers, and tools. When Dewberry reached out to Esri with its proposal in November 2024, the team was looking to use two specific pieces of ArcGIS Living Atlas content: the World Imagery map, which provides high-resolution aerial and satellite imagery from around the world, and the Building Footprint Extraction – USA pretrained deep learning model, which automatically extracts building footprints from high-resolution imagery sources.

The timing of Dewberry’s request was excellent. The ArcGIS Living Atlas imagery team was already preparing to publish a new tutorial that covered how to use AI to extract information from World Imagery. The tutorial includes a step-by-step workflow using a pretrained deep learning model to detect building footprints from World Imagery. The Alaska project’s requirements were a great fit for the workflows and capabilities featured in the tutorial, so the project served as a practical application of it.

Comprehensive and Accessible Geodatabases

The Dewberry team leveraged several imagery sources for this project, including piloted and unpiloted aerial collections sourced from the State of Alaska, the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and Alaska Remote Imaging. Esri’s World Imagery map served as the best available and most recent imagery for 46 of the 64 communities.

Following best practices, the team applied a rigorous quality-assurance process as part of the feature extraction workflow. To help efficiently identify irregularities, the team used ArcGIS Pro to calculate variables such as vertex count and perimeter-to-area ratio. The team then reviewed all 17,000 building footprints from the 64 communities and refined them where needed to improve the overall accuracy.

In total, 65 file geodatabases will be created—one primary geodatabase aggregating vector datasets for all communities, and 64 individual geodatabases containing community-specific vector data. Each geodatabase will include eight feature datasets, grouped by data theme, and contain numerous feature classes, depending on available data for each community. All data will be stored as an Esri file geodatabase with metadata following standards from the International Organization for Standardization and detailed source lineage documentation.

The resultant geodatabases will be made accessible through multiple platforms, including the State of Alaska Geoportal, NOAA’s Data Access Viewer, and Esri’s ArcGIS Living Atlas. These platforms provide user-friendly interfaces for exploring, visualizing, and accessing geospatial data.

While the project is addressing specific data needs for emergency response and resilience planning, NOAA is also seeking to invigorate community mapping programs and document lessons learned. Contributing to Alaska’s mapping initiatives and envisioning a thriving network supports a variety of long-term and complex challenges, including community relocation, behavioral health, and food sovereignty.

“It’s about making sure every community has access to the tools and information [it needs] to support planning, development, and long-term resilience,” said Palmer.