I was a 27-year-old GIS analyst in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, when I volunteered to support my company’s response to Hurricane Katrina. The hurricane devastated communities and showed a nation that while we can’t control nature, we can control how we respond to it. I didn’t know it then, but those first two weeks would set the trajectory for the next 20 years of my career.

What was supposed to be a short deployment to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, quickly turned into nine months on-site, where I stayed to manage and lead the GIS unit—a 24-hour mapping shop with analysts working around the clock to supply responders with operational and situational data.

It was there that I learned my first true management lesson: Success isn’t about how much data gets processed; it’s about how well others see what GIS can do. Managing people through possibility rather than pressure became the foundation for how I lead teams.

One of my first nights in Baton Rouge, I went back to the command post at 2:00 a.m. The head database administrator (DBA) looked up and asked, “What are you here for?”

“GIS,” I said.

He laughed. “GIS is easy,” he responded.

Instead of throwing my laptop bag at him, I made it my mission to show him how GIS, databases, and systems all had to work together for us to succeed. GIS is a team sport and a critical component of emergency operations.

That same DBA is now one of my favorite collaborators and friends. Together, we’ve helped move the perception from “GIS is easy” to “GIS is essential.” His technical expertise and willingness to evolve have pushed our team’s use of GIS forward. I am forever grateful to him and every teammate who’s helped shape what GIS in emergency response has become: a trusted partner in saving lives and restoring communities.

-

During emergency response operations, GIS is a trusted partner in saving lives and restoring communities.

Improvising Under Pressure: 2005–2010

Those early years were raw, exhausting, and transformative. I was still learning what it meant to manage people, technology, and expectations in a nonstop operational environment. GIS lived in the world of ArcGIS Desktop, on-premises servers, emailed shapefiles, and binders full of printed map books. Hundreds of e-size (huge) maps and stapled data tables filled command posts, and 24-hour turnarounds were considered successes.

But in that chaos came some clarity: Managing isn’t about control, it’s about building teams and trust among them. That means listening to analysts who see better ways to automate a task, encouraging DBAs to spatially enable data, and recognizing how exhausted a GIS analyst can get pumping out operational maps.

These experiences taught me that managing through possibility means taking frustrations and turning them into better ways to use technology. Our goal wasn’t to make prettier maps; it was to move operations forward faster and with more accuracy. That mindset built trust and earned GIS a seat at the table.

The Shift to Digital Collaboration: 2010–2015

Everything with GIS began to change with the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, which caused the largest marine oil spill in US history; the 2011 tornado in Joplin, Missouri, that damaged nearly 8,000 buildings and killed more than 150 people; and Hurricane Sandy, which ravaged areas from the Caribbean to eastern Canada in October 2012 and caused $65 billion (about $85 billion today) in damages in the United States. Esri ushered in ArcGIS Server to replace ArcIMS and launched ArcGIS Online. The enterprise GIS mindset began to emerge.

Managing GIS in this era required translating between the old and the new. This meant helping field staff, analysts, and IT teams see that cloud-based systems weren’t a burden and weren’t replacing them, but empowering them.

During this time, an IT architect on my team asked to use an $8-per-month cloud coupon to stand up an early web-based GIS for operations. That small experiment became a model for our company’s enterprise response systems. There, I learned that managing is about creating space for curiosity and calculated risk within the emerging technology landscape. When people feel trusted to try new ideas, innovation follows.

From Static Maps to Dynamic Data: 2015–2020

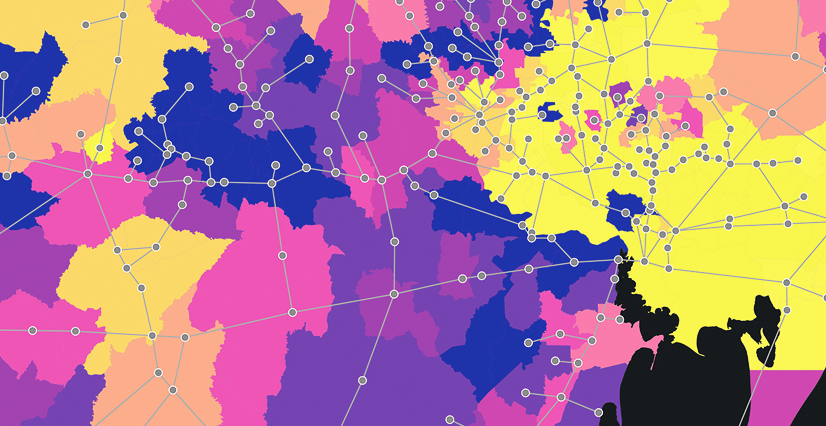

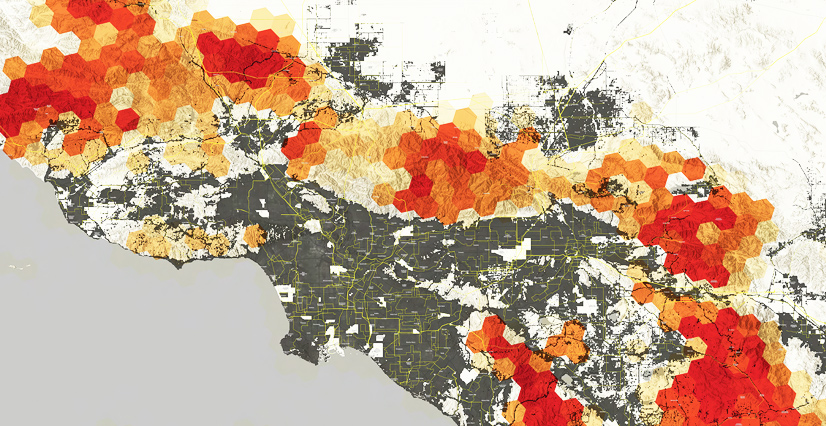

Technology leaped forward again. ArcGIS Collector, ArcGIS Survey123, ArcGIS Dashboards, and ArcGIS StoryMaps transformed how data was collected and shared—not just within operational teams but also with the public. During Hurricanes Harvey and Irma, as well as wildfires in California, the turnaround for situational data dropped from days to minutes.

Managing teams through this era meant balancing opportunity with overload, asking lots of questions, and not being afraid to try something new. A common question I asked was, “What did we learn during the last disaster response, and how can we do better next time?”

Listening to what works and what doesn’t helps teams design better workflows after every response.

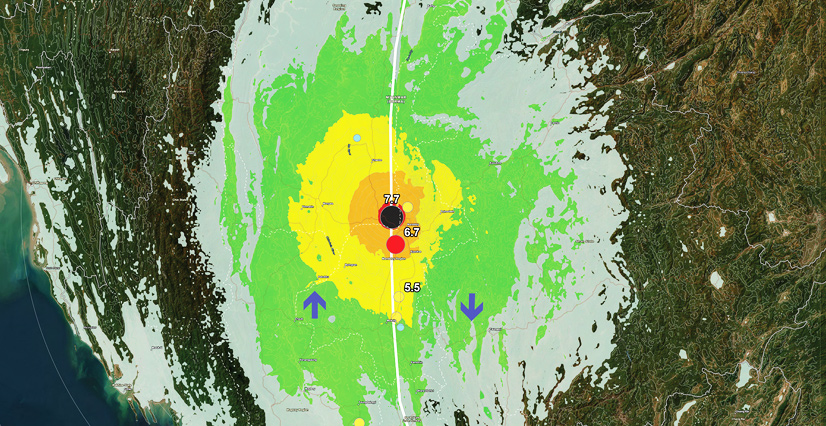

The Rise of Intelligent Response: 2020–the Present

When COVID-19 hit, GIS moved from the command post to the world stage. GIS-based dashboards became public lifelines, informing millions in real time how and where the disease was spreading. Every data point carried weight, and with that visibility came pressure for teams to be accurate and responsive.

Managing through this period required more than keeping systems running; it entailed keeping people motivated and connected. Cloud-based platforms and systems pushed technology forward, but teamwork and trust enabled successful implementations.

This experience reshaped how I manage today. The technological environment integrates AI-driven analytics, automation, drones, and real-time mapping, but the core principle remains the same: Technology only works when people collaborate and listen to each other.

GIS in disaster response is no longer reactive; it’s proactive, predictive, and purpose-driven. Managing through possibility now means empowering others to question assumptions, innovate responsibly, and build teams that carry the mission forward.

Developing Leaders

Over time, I learned that my job wasn’t to have every answer; it was to create the conditions for others to find them. Managing today means giving people space to innovate, permission to take risks, and the confidence to challenge “the way it’s always been done.”

People thrive when they feel heard and trusted. Listening is what transforms management into mentorship. It shows respect for the expertise and lived experiences of those closest to the data, systems, and disaster sites.

The teams I helped guide now understand their mission deeply: to serve responders and communities by giving them reliable, real-time information. Their hearts are in the world, their tools are modern, and their management style is rooted in trust, empathy, and continuous listening.

Full Circle

That night in Baton Rouge responding to Hurricane Katrina was the start of a journey I never could have imagined. The colleague who once said “GIS is easy” is now someone I can’t imagine working without. Our friendship is built on listening and the belief that technology and data serve communities for good.

Together, he and I have created more than dynamic systems and dashboards. We’ve built a culture of trust and possibility. From producing static maps to designing intelligent, connected platforms, our work has evolved from “easy” to essential, just as our teams have.