For most of my career, I’ve worked with small uncrewed aircraft systems, or drones—from the days when people built them at home to now, as they become a viable commercial enterprise. I remember when excitement about drones was real, and I took pictures with them for novelty’s sake. Fast-forward to today: I don’t think I’ve used a drone to take a photo for something other than mapping or inspection purposes for several years.

The drone industry journey has been a rollercoaster of hype—a cycle of excitement and disillusionment for many people in the GIS world and beyond. We’ve been through highs and lows. Now, we stand at a crucial point, looking at where the drone industry currently is and where it is likely to go in the next few years. From my vantage point, where it’s headed is closely related to mapping and GIS technology.

Understanding the Hype Cycle

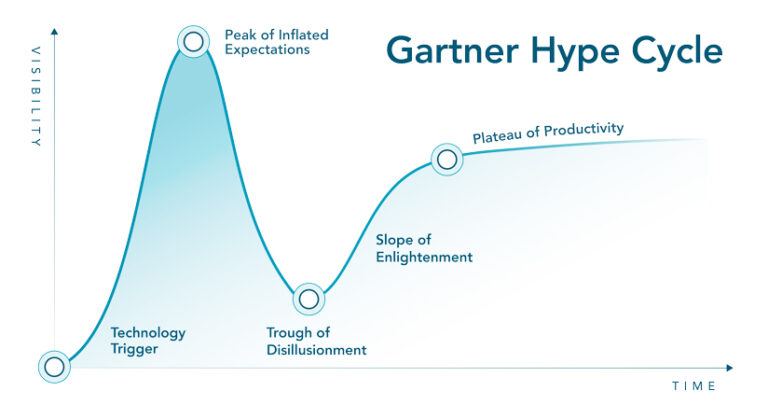

To interpret the drone industry’s trajectory, it helps to look at the Gartner Hype Cycle. Created by a Gartner analyst, the Gartner Hype Cycle illustrates the typical life cycle of emerging technologies. It maps a technology’s visibility over time, starting with a “Technology Trigger.”

For drones, this trigger was the commercialization of small, lightweight, and inexpensive components—such as inertial measurement units, compasses, and GPS units—that were initially created for the smartphone and video game industries.

For those of us who work with drones, this innovation sparked our imaginations and led the industry to a “Peak of Inflated Expectations.” About 10 years ago, there were many ambitious venture capital funding rounds. It was an exciting time. Promotional videos featured monkeys flying drones. One venture-funded company even started its own venture capital fund with its borrowed dollars. The hype was palpable, culminating in the first successful delivery via drone in the United States in 2015, when a drone carried medical supplies from an airport to a health clinic in rural Virginia.

But what goes up must come down. Neither the hardware nor the regulatory environment could keep pace with the hype, leading to the “Trough of Disillusionment.” The reality of technology limitations set in. Government restrictions, especially in the United States and Europe, hampered real-world implementation. There were headlines about the fall of the drone industry. One company shut down in 2018 after burning through more than $100 million. Much-anticipated drone-based package delivery programs are still largely proofs of concept.

Now, however, I believe we’re climbing out of that trough and ascending the “Slope of Enlightenment.” This is where companies find patterns of use that are practical, productive, and profitable. It’s a phase marked by growing confidence in the technology. It’s no longer a science experiment; for organizations to adopt it, the technology needs to foster high levels of productivity and be better than what came before. As more organizations see success, they pave the way for others to follow, and it becomes easier to progress.

Enlightenment in Action

One example of this advancement is an ambitious undertaking by project development and construction firm Skanska Norge AS. The company is working to connect five Norwegian islands to the mainland via a 22-mile stretch of roadways, bridges, and subsea tunnels. Naturally, conducting site visits and monitoring construction progress presented a massive logistical challenge—but drones have helped make it feasible.

For this project, a Skanska Norge drone team is using the ArcGIS Flight planning app to automate data collection with a Phantom 4 RTK drone. The collected imagery is then uploaded to the cloud and processed in Site Scan for ArcGIS. This allows the team to create highly accurate 2D orthomosaics, digital elevation models, 3D point clouds, and 3D meshes. On-site project engineers overlay computer-aided design (CAD) files on drone data to compare as-built versus as-designed conditions in near real time. Cloud-based integrations between ArcGIS and Autodesk technology allow the team to see construction data in concert with their GIS data, including terrain and environmental information. Employees across the company have access to the cloud-based data, and island residents and other stakeholders can see the project’s status.

Another example comes from environmental engineering consulting firm Dudek, which employs drones and ArcGIS technology to streamline land surveying operations. Staff used ArcGIS Flight for flight planning and data collection, along with Site Scan to process and analyze the data. With this integration, Dudek’s clients were able to see dynamic visualizations of project data, including topographic information and easements, in near real time. By adopting this technology, Dudek saved more than $80,000 in one year and improved its workflow efficiency.

A third example stems from project management firm OCMI, which used Site Scan to track the movement of construction materials and provide progress reports while building San Diego, California’s new Snapdragon Stadium—home to two professional soccer teams and San Diego State University’s football team. OCMI used drones to capture imagery of concrete being moved from an old stadium to be reused in the new stadium and then processed the imagery using Site Scan. This enabled OCMI to provide stakeholders with up-to-date images, 2D orthomosaics, and 3D mesh models while helping the company quantify material stockpiles and validate contractor data. This improved project management and led to significant cost savings.

These companies’ successes demonstrate how organizations that lean into innovation can standardize the use of drones and prove their value. It is evidence that the wild ride the drone industry has been on so far is stabilizing—that it’s moving past the research and development phase and arriving at established standard practices.

The Future Is Boring, and Probably Profitable

What’s next for the drone industry? Likely, drones will become boring. The final stage of the hype curve is the “Plateau of Productivity.” This is where a technology becomes so ingrained in workflows that it’s no longer considered innovative. Think about how automatic sprinklers and robot vacuums work. They feel pretty normal, don’t they? That’s where drones are headed.

The last piece of the puzzle—for most countries with drone regulations, at least—will be getting drones to fly autonomously, without a drone pilot at the controls. In many countries, this is possible to do now with a waiver, and more widespread regulatory approvals are in the works. When these issues are addressed and drones are automated, reliable, and trustworthy, organizations will be able to use them regularly to increase productivity, develop a larger user base, generate higher profits, and stimulate technological advances.