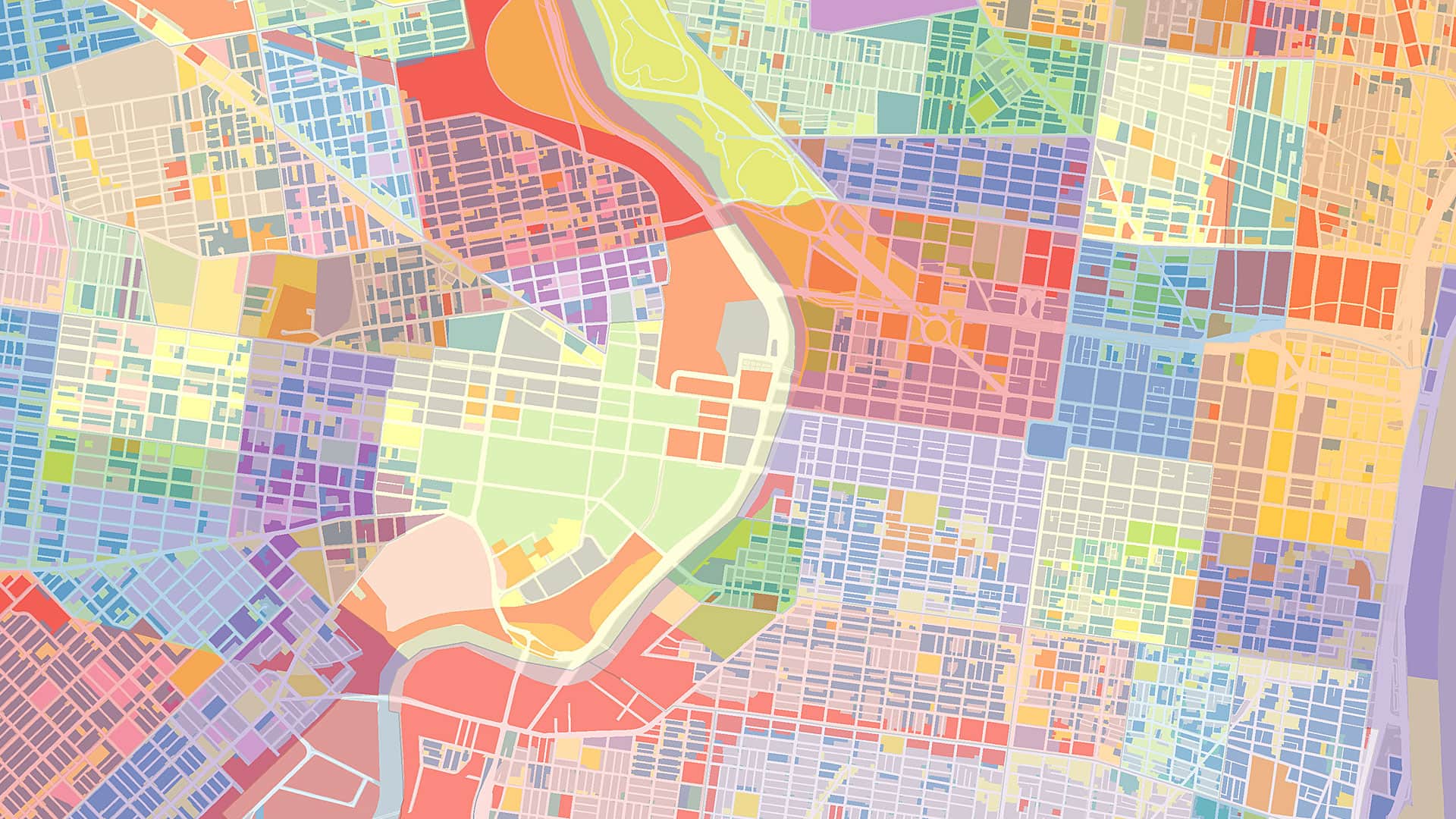

Maps are more than simple representations of physical space. They shape people’s understanding of the world, influence political and cultural narratives, and reflect historical and ideological perspectives. The phrase “if it’s on a map, it matters” underscores the profound power of cartography in defining not just places but also territorial claims, identities, histories, and contemporary circumstances.

One of the most potent elements of this power lies in geographic names. These names are not just labels or arbitrary designations; they are imbued with cultural meaning, history, political messages, and more. Naming a place is an act of authority, as it reflects who controls a space and whose narratives are prioritized.

For example, colonial powers often renamed places, erasing Indigenous names and replacing them with ones that reflected their own heritage. This practice was a form of cultural domination, symbolizing control over both the land and its history. In North America, Africa, and Australia, Indigenous names were frequently replaced by European names, signifying the imposition of foreign rule. In contrast, the revival or preservation of Indigenous names represents efforts to reclaim cultural heritage and assert identity.

Let’s take a look at some of the ways the names on maps both shape and are shaped by politics, identity, and culture—and how commercial interests and technology now play into this.

The Marks of Territorial Disputes and Conflicting Claims

Maps are often used to stake political claims, and geographic names are central to this process. When a country names a disputed territory on its official maps, it is making a statement about sovereignty.

Examples abound in waters where multiple nations lay claim to various islands and maritime areas. The naming of these territories reinforces each country’s territorial assertions, even when those claims are contested by other nations or international law.

Similarly, the naming of cities and regions in conflict zones reflects political allegiances. In Israel and Palestine, for instance, the naming of places can be a politically charged issue. Additionally, maps produced in other parts of the world might label the same area differently, reflecting the perspective of the mapmaker’s country or ideology.

National Identity and Cultural Heritage in Place Names

Geographic names play a crucial role in national identity. Countries undergoing political or cultural change often rename streets, cities, and even regions to reflect their evolving identities. After the fall of colonial regimes or oppressive governments, renaming places is a way to reject past dominance and assert self-determination.

For instance, after gaining independence from Britain, India changed many of its city names to better reflect Indigenous heritage. Bombay became Mumbai, Madras became Chennai, and Calcutta became Kolkata. These changes were not just cosmetic but also symbolic, marking a return to local identities and breaking away from colonial legacies.

Similarly, in post-apartheid South Africa, the renaming of places was an effort to honor figures from the anti-apartheid struggle and recognize Indigenous and African heritage. Pretoria, the administrative capital, has seen parts of the city renamed to reflect Indigenous history, demonstrating how maps can serve as tools of cultural redefinition.

Changing Historical Memory Through Erasure and Resistance

When a place is renamed, it can also be an act of historical erasure. In cases where powerful nations or groups impose new names, they can effectively remove the memory of previous inhabitants and their cultures. This has happened throughout history—from the Romans renaming their conquered territories to the Soviet Union renaming cities to reflect its Communist ideology.

Resistance to such expunging can take the form of restoring old names. One example is the movement in Turkey to recognize and reinstate the original Armenian, Greek, and Kurdish names of towns and villages that were changed during periods of nationalist policies.

How Commercial Interests and Technology Impact Names on Maps

In the digital age, the way maps are created and distributed has changed, yet the power of geographic names remains significant. Online mapping services such as OpenStreetMap, Google Maps, and Apple Maps influence global perceptions of geography. The ways these organizations and companies name disputed regions or use specific terms for places can spark controversy. For instance, debates have arisen over whether mapping services should refer to the waters between Saudi Arabia and Iran as the “Persian Gulf” or the “Arabian Gulf,” reflecting the geopolitical tensions between Iran and other countries in the Middle East. A more recent debate has emerged over the United States renaming the “Gulf of Mexico” the “Gulf of America.”

Additionally, commercial interests play a role in place naming on maps. The practice of selling naming rights for stadiums, parks, and landmarks demonstrates how place-names can be commodified. This phenomenon extends to digital mapping, where businesses compete for visibility on search engines and popular mapping platforms, influencing what people see and how they navigate spaces.

The Enduring Influence of Geographic Names

In an era of globalization and digital mapping, the power of geographic names is more relevant than ever. The choices made by governments, corporations, and digital platforms determine which names are seen and recognized. This, in turn, influences people’s perceptions of geography, history, and current events.

As long as names appear on maps, they will continue to matter, shaping the way people understand and navigate their worlds. Thus, it is crucial to preserve their accuracy and meaning on maps. Properly displaying place-names ensures respect for local traditions while providing valuable context for understanding the geographic landscape.