Over the past two decades, there has been a dramatic increase in how much geospatial data is generated for health research, as well as in the number of related tools and spatial methods used to study that data. From analyzing infectious disease outbreaks and patterns in cancer rates to modeling how environmental risks impact substance abuse levels, these new datasets, technologies, and processes are transforming our understanding of how environmental factors and social influences interact with health.

But we have not yet achieved the full potential of what new developments in GIScience can do for health research. That will require interdisciplinary collaboration among geographers, biomedical scientists, and public health practitioners.

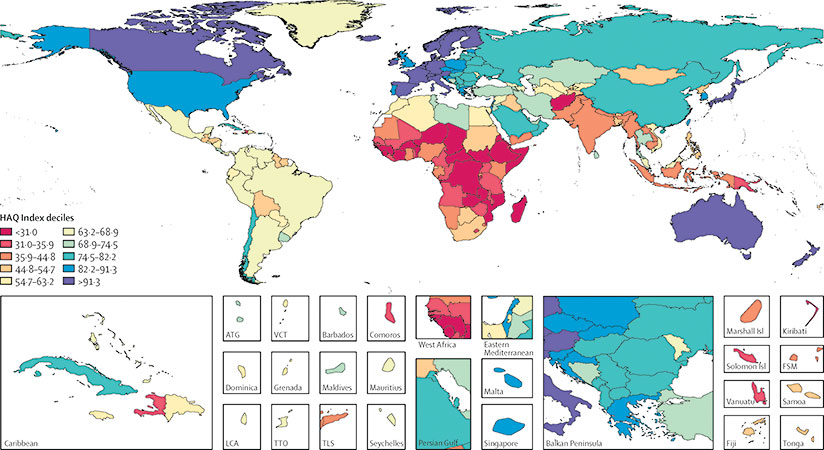

Given that health researchers now increasingly have access to highly detailed genetic and epigenetic information, there is a similar need to get more precise information about environmental or social contexts that may factor into health issues. This is where geography—with its emphasis on place, integrative science, and methods for spatially organizing and understanding coupled human and natural systems—becomes essential. It is also where GIS—with its capacity to integrate and correlate vast amounts of detailed quantitative environmental data with observed conditions (such as infectious diseases, cancer, obesity, mental illness, and addiction)—becomes critical, especially for medical research and practices that aim to address the complex ways in which genetics and environmental factors relate to disease.

Developments in distributed computing are further enabling new research frontiers in health. It is now possible to use GIS services remotely to perform sophisticated spatial analyses and model complex spatial health processes at the individual level rather than solely for the aggregate. For example, if researchers equip an asthma patient with a GPS device that tracks air quality in real time, they can get meaningful measurements of his or her exposure to disease-causing pollutants, such as particulate matter or sulfur dioxide. Indeed, this is far more precise than tracking this at the county or population level.

Additionally, the Internet of Things (IoT) has given value to the embedded GPS and GIS in so many consumer devices that individuals now have the power to gather their own geospatial data and participate in various online-based citizen science health projects. Despite the obvious issue of quality assurance, it is clear that the crowdsourced georeferenced health data being volunteered by millions of people has fascinating potential not only for medical research but also for delivering health services.

Of course, making advances in the spatial analytical methods for mining and interpreting this kind of data will be integral to implementing promising new approaches in health service delivery, including mobile health services (mHealth) and electronic medical records. More breakthroughs will also be needed to make health care accessible to everyone and to fix ongoing global health disparities.

The American Association of Geographers (AAG) has worked with leading geospatial health scientists from around the world to form a new organization, called the International Geospatial Health Research Network (IGHRN), that will share the latest research in geospatial health methods and technologies. The group is also responsible for fostering international health-based collaboration across borders, as well as bridging the gap between GIScience health research and the needs of health practitioners on the ground.

The stakes are high. It is incredibly challenging to control traditional and newly evolving diseases. And, as Microsoft cofounder Bill Gates recently pointed out, we are falling short in preparing the world for the “significant probability of a large and lethal modern-day pandemic occurring in our lifetimes.” Based on studies from several global health research institutions, he is urging the United States government to take the lead on this. It is imperative that we advance and implement new spatial health research, methods, and infrastructure to address these health challenges.

AAG’s collaborations with organizations around the world also suggest that we need new institutional and educational models for integrating geography more fully into health research and practice. Public policies and institutional initiatives that incorporate spatial data and analysis into global health research and practice can generate extraordinary discoveries in health research and produce new efficiencies in delivering health services to people no matter where they live.

To engage with these issues more deeply, consider participating in the special IGHRN symposium that will be held during the AAG’s annual meeting in Washington, DC, April 3–8, 2019.

Contact Doug Richardson at drichardson@aag.org.