The enhanced capabilities of GIS at a time when its use is rapidly expanding—particularly by organizations responding to the COVID-19 pandemic—have caused greater concern over establishing and maintaining effective GIS governance. Organizations need to think big but focus on the details to establish an effective GIS governance program

The CIO of a medium-sized city government was concerned. The city was in the midst of a large-scale digital transformation that promised to reinvent how services were delivered to its residents. The city had committed millions to revamping department systems and investing in critical smart infrastructure.

Early results were promising. The city had enjoyed a high-profile win by integrating road disruption notifications with social media. Notification of planned and unplanned disruptions on a map in real time was a hit with residents. However, the CIO noticed a concerning trend. This win created a demand for new map-based solutions that was stretching his team’s ability to deliver.

In the past, GIS was acknowledged as an important system of record for city assets as well as the home for most of the city’s mapping information. This new demand had pushed expectations for location-driven applications to new levels. But without a way to manage demand, set expectations, and nurture the development of these apps, the CIO recognized he was facing failure. Without strong GIS governance, how could he deliver on the promise to reinvent the city through digital technology?

This situation is not unusual. Much of the success with GIS comes not from the implementation of the technology but its ability to build a location capability. This means marrying the technology of GIS with the science of geography and ingraining it in the organization’s DNA. A well-developed, robust GIS capability is the foundation on which the dreams of a location-based digital transformation are built. To do this, good governance is critical.

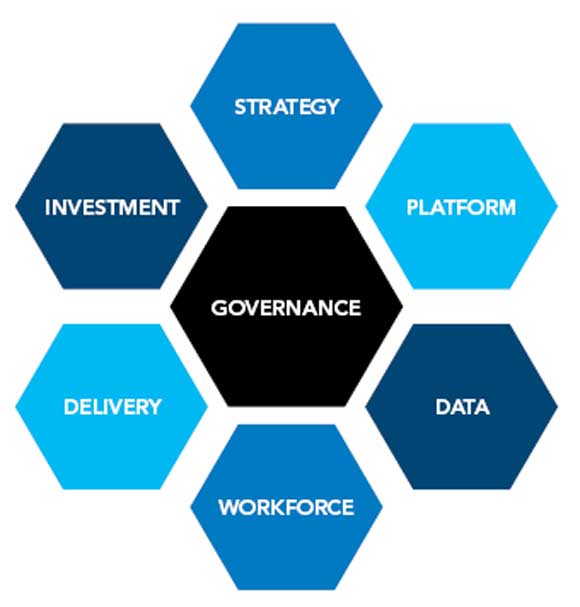

By governance, we mean the system of control. This control extends to the applications and infrastructure that drive your location platform, the data at the heart of your maps and information products; the people who build and support the platform, and the capital used to grow and sustain your location capability.

In short, governance is one of the most important factors determining the long-term success of a GIS. Without good governance, plans stall. They are doomed, as the poet W. H. Auden put it, “each to his own mistake.” This article discusses some of the reasons why organizations fall short in this regard and looks at a comprehensive framework for GIS governance.

In short, governance is one of the most important factors determining the long-term success of a GIS.

Where Do Organizations Go Wrong?

GIS governance often falls short for several reasons.

First, governance is generally a poorly understood topic in GIS circles. It’s not uncommon to hear managers say that they know they need governance, but they don’t know exactly what it means. This speaks to a lack of a shared understanding of why governance exists in the first place. This lack of understanding often results in piecemeal, unstructured attempts at implementing governance in a single area such as data access or application ownership. These are fine starting points but don’t constitute a comprehensive approach when considering the range of decisions required to sustain a modern GIS.

Second, GIS governance programs often lack attention to the ongoing job of governing. It’s one thing to establish a steering committee and assign responsibilities, but another to keep the program going beyond a semiannual meeting. A well-executed program requires the commitment and energy to govern day-to-day.

Third, governance of GIS relies too much on other, broader levels of governance. To be clear, GIS doesn’t exist in isolation. So, it’s not surprising to see governance of GIS fall under an organization’s IT governance or data governance programs. The problem is that these corporate-wide governance programs are often too general and overlook some of the unique aspects of GIS that require focused attention. These aspects include platform decisions, unique geospatial data considerations (e.g., standards, models), and worker skill sets. Effectively, this speaks to the hierarchical nature of governance—where higher levels dictate broad standards (e.g., corporate data privacy policy) and lower levels shape those standards appropriately (e.g., geospatial asset information access rules).

Last, governance is a cultural shift that requires discipline. For some, this means rules, and rules mean bureaucracy. Organizations that fail in their governance ambitions often fail because the opposition to change was too much to overcome. A systematic and explicit approach to governance is needed so that stakeholders understand the value of taking this on.

A Comprehensive Definition

To address these challenges, we need to start with a broad definition of governance. Governance is about decisions and decision-making. Specifically, it’s about defining the major decisions that need to be made with regard to an organization’s GIS (the decisions) and how and by whom those decisions are made (the decision-making). Done correctly, governance creates a system of accountability that defines and enforces the rights of stakeholders.

To be clear, governance is not management. Governance is about setting direction. Management is about executing according to those directions. The distinction is important because much of the GIS conversation has traditionally centered on management topics. While management is vital, we want to draw a clear line between the two to keep the focus on doing the right things (governance) versus doing things right (management).

To be clear, governance is not management. Governance is about setting direction. Management is about executing according to those directions.

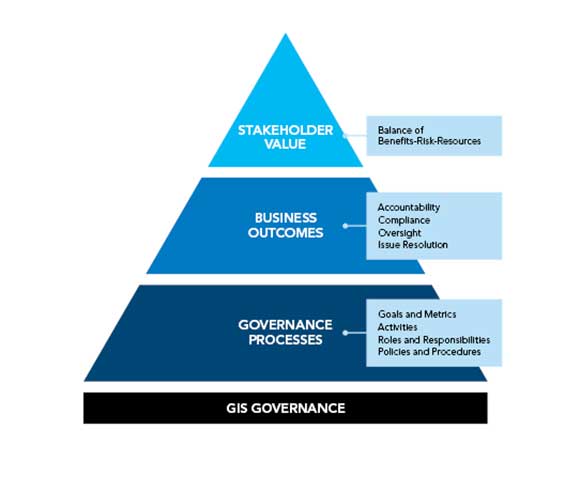

In practice, governance involves executing a set of processes that are defined based on the major GIS decision area they support (which will be discussed in the next section). Each process is composed of a defined set of goals, key performance indicators (KPIs), structured activities, roles and responsibilities, and policies and procedures.

Collectively, governance processes drive key business outcomes. These include improved accountability, compliance, delivery oversight, and resolution of issues. Effective governance brings structure to decision-making and clarity over responding to change.

Ultimately, governance creates stakeholder value. With greater accountability and control, the organization is positioned to make better decisions with its GIS—decisions that align with and support the organization’s strategic mission and work to find an effective balance among the competing constraints of benefits, risk, and resources.

A Structured Framework

With governance defined, consider the specifics of implementing governance for GIS. Based on my experience, I’ve identified six major decision areas for GIS called domains. Domains are composed of more than 20 governance processes that have been compiled into best practices. Building a successful governance program requires a clear focus and maturity across these areas.

Strategy Domain

Smart organizations have a clear vision of where they want to go with GIS and how to get there. Effective GIS governance means establishing core principles, determining short- and long-term objectives, defining the optimal organizational structure, and monitoring progress against the plan. Governance in the strategy domain supports alignment of the GIS vision with the business vision. Specific governance processes included in this domain are guiding principles, the strategic plan, stakeholder relationships, organizational structure, and innovation.

Platform Domain

Applications and infrastructure are the foundation of GIS. Many decisions must be made that impact the integrity of the technical environment and alignment with strategy, now and in the future. This cuts across the vast world of location-based technology including mapping platforms, geoanalytics solutions, mobile applications, and imagery management. Governance in the platform domain enables a sustainable, flexible, and fit-for-purpose GIS technology architecture. Specific governance processes included in this domain are technology architecture, solution portfolio, platform access, and platform performance.

Data Domain

Data is at the heart of GIS. This is true whether we’re talking about geospatial or nongeospatial data, structured or unstructured data. Effective GIS governance establishes consistent GIS data standards, architectural models, data usage, access controls, accountability across the data life cycle, and quality controls. In addition, a key architectural decision relates to the structure of data ownership. This refers to ownership of systems of record versus ownership of derived sources and the business rationale behind decision rights. Specific governance processes included in this domain are data architecture, data usage, data stewardship, and data quality.

Workforce Domain

GIS requires unique skills and competencies across a range of technologies and disciplines. As a broad enabler, GIS is also leveraged by all manner of stakeholders. This means effective GIS governance considers development of the competencies, talents, and external relationships across the entire workforce. Governance in the workforce domain supports sustaining a skilled and informed workforce. Specific governance processes included in this domain are training, development, talent management, and partnerships.

Delivery Domain

An effective GIS is well supported and delivered as a service to the business. Good governance supports practices that promote efficient delivery of GIS as a service including needs capture, delivery, communication, and change management. Governance in the delivery domain establishes an effective GIS operation. Specific governance processes included in this domain are service management, communications, business needs, and change management.

Investment Domain

The end game for GIS governance is an answer to the question, where do we invest our resources? Effective GIS governance provides a mechanism for prioritizing investment decisions and monitoring progress. Governance in the investment domain aligns resources with GIS and business priorities. Specific governance processes included in this domain are budget management and investment prioritization.

Management Structure

To bring it all together, an effective governance program requires a strong management structure. This means organizing stakeholders into meaningful teams and establishing clear reporting relationships. While there is no single management structure that works for all organizations, a three-tiered structure is common. The first tier is a group of influencers (e.g., sponsor, executive champion, IT champion, and stakeholder champion). The second tier is a steering committee. The third tier typically consists of strategy, technical, and operational working groups.

This management structure represents general groupings of key governance roles. In many cases, individuals will play multiple roles and contribute to multiple aspects of governance. This is especially true for smaller organizations.

Influencers

This group is made up of influential and vocal stakeholders who do not make the final decisions on the GIS but whose input is critical to its success. They’re generally interested in business value, risk, and alignment with overall business objectives.

Steering Committee

The steering committee is the primary decision-making body for the organization’s GIS. It is tasked with setting the overall direction and approving key GIS decisions.

Strategy Working Group

This group is generally responsible for developing the governance processes supporting the strategy and investment domains. Depending on the size of the organization, these stakeholders might sit on other working groups or be a part of the steering committee.

Technical Working Group

This group is responsible for developing the governance processes supporting the platform and data domains. Stakeholders in this group might also participate in corporate IT governance and data governance programs. They often act as an important conduit to these other, broader governance programs.

Operational Working Group

The operational working group develops the governance processes supporting the workforce and delivery domains. These stakeholders are typically involved closely in the day-to-day operations of providing GIS services. They may also work closely with broader IT service delivery programs.

A Valuable Undertaking

Implementing governance for GIS is a challenging but extremely valuable undertaking. It takes focus and commitment. With a bit of structure, however, any organization can achieve the benefits of good governance. This doesn’t mean it happens overnight. By focusing on key problem areas and implementing processes and management structures that will bring these areas under control, organizations can start down a path that will lead to good governance.