For Native Americans living in North Dakota, GIS technology has helped address a significant question: How can their voting rights be preserved in the face of a new, statewide voter identification law?

Just weeks prior to the 2018 midterm elections, the US Supreme Court voted not to intervene and let stand a lower court decision upholding a state law that requires that all North Dakota residents present identification with a street address before being allowed to vote.

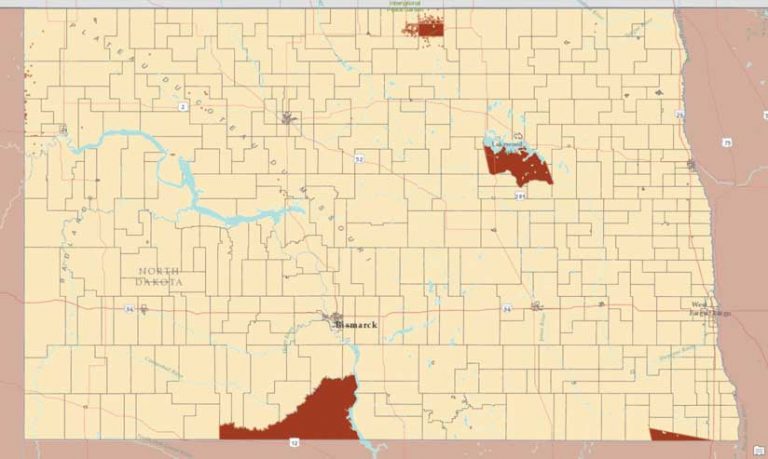

Many of the state’s nearly 30,000 Native Americans live on reservations and do not have street addresses. Reservations have dirt roads, streets without signs, and nearby structures identifiable by their features, not numbers. Instead of addresses, many residents use post office boxes.

But the use of post office boxes is no longer acceptable under this new legislation, which went into effect 30 days before the November 2018 midterms. Even though supporters of the law said it was necessary to prevent voter fraud at the ballot box, the law also threatened to prevent many residents on reservations from exercising their right to vote.

Four Directions, a Native American voter rights advocacy group that has been fighting against that law’s restrictive impact since its inception, reached out to Jean Schroedel, a professor of politics and policy at Claremont Graduate University (CGU). Having worked on Native American voting rights (and with Four Directions) in the past, Schroedel was poised to find a solution for the affected residents of the Standing Rock, Turtle Mountain, and Spirit Lake reservations in North Dakota.

Schroedel turned to her colleague Brian Hilton for help. Hilton is a specialist in GIS in the university’s Center for Information Systems & Technology, director of the advanced GIS lab, and a longtime user of Esri technology. The two had worked together on a related matter several years prior regarding the court case Wandering Medicine vs. McCulloch. That case dealt with voter access for members of isolated tribes in Montana. Hilton had helped illustrate with geographic data that voter turnout was significantly impeded due to travel distance, geographic obstacles, and other socioeconomic factors.

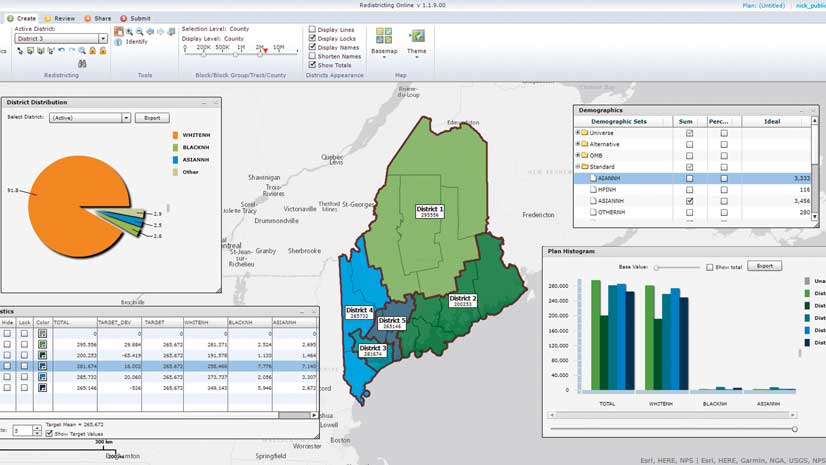

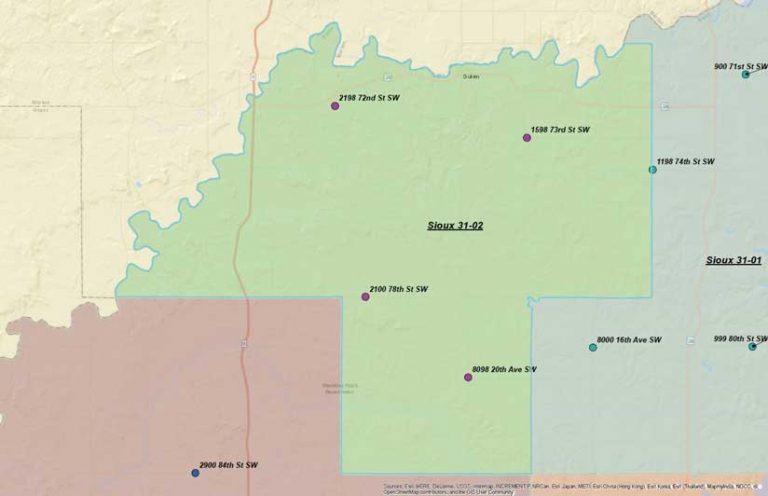

This time, with the midterms drawing near, the project required haste. With just two weeks to Election Day, Hilton went to work. After obtaining shapefiles of the voting precincts in North Dakota from the Harvard Election Data Archive, he selected the precincts that intersected the Standing Rock, Turtle Mountain, and Spirit Lake reservations. He split those precincts into four roughly equal areas. He identified locations in each precinct quadrant that were not on an existing house but were on a physical road that had a name (e.g., 35th Avenue SW).

“It was somewhat laborious, as you have to zoom in and zoom out [of the map] and see if there are buildings or anything nearby to find a location that’s suitable for an actual address,” explained Hilton. It required that he use both ArcMap and ArcGIS Online to constantly consult Imagery, Streets, and OpenStreetMap basemaps.

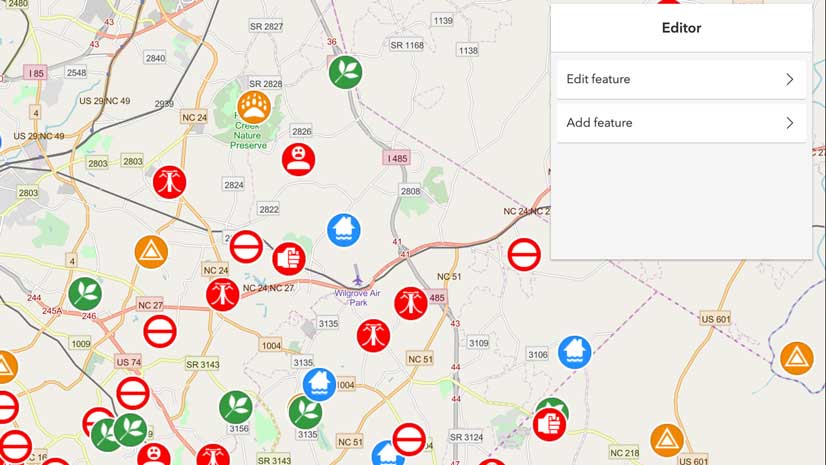

At each location suitable for an address, he created a new point and assigned it a street and address using the Burkle addressing system to determine the street number. [The Burkle addressing system was devised for assigning road names and addresses in rural areas and is used in North Dakota to establish rural addresses for mail delivery and 911 response.] For each point, Hilton added address information to a spreadsheet and created corresponding maps of each precinct quadrant.

To demonstrate that address geocoding was not possible in many locations in the reservations, Hilton also used the ArcGIS API for JavaScript to create an online map that showed that addresses for many locations did not exist in the database. For many locations, the only information that could be provided was latitude-longitude coordinates. The tribes used the online map to explain why Hilton needed to create addresses for Native American voters living on the reservations.

The spreadsheets and PDF maps Hilton produced were sent to Four Directions. The organization then brought these materials to polling places so Native American voters could point to their residence and have an address given to them. Four Directions even funded the cost of printing new IDs with street addresses and helped shuttle residents to and from polling places.

The result? Voter turnout for the Standing Rock, Turtle Mountain, and Spirit Lake reservations was the highest ever recorded. It is anticipated that similar increases could occur if these methods were widely distributed to other places with similar challenges. If the issue of disenfranchisement based on a street address requirement arises again, the tools are now in place to combat it.

Hilton observed that Native Americans could further benefit from this work, as it could provide first responders with a better method of identifying the location of 911 calls and other related emergencies. The impact of this work has also received extensive coverage including articles in Time magazine and the New York Times.

I can’t think of another time where I felt that the research...mattered quite as much.

The collaboration of Schroedel and Hilton, which brought the university’s politics and policy program and information science program together to find a solution to the problem, epitomizes CGU’s emphasis on transdisciplinary efforts. The university’s teaching philosophy is grounded in the belief that complex problems require scholars to transcend academic boundaries to find the best solutions to real-world challenges. As Schroedel said in an interview on CGU’s YouTube channel, “I can’t think of another time where I felt that the research…mattered quite as much.”

For more information about CGU’s use of Esri technology and the university’s Center for Information Systems & Technology, contact executive director of Advancement Communications Nick Owchar at nick.owchar@cgu.edu.

Learn more about CGU’s GIS program. Read more about Schroedel’s work related to Native American voter suppression.