If there’s any field where expertise was once a significant barrier to entry, it’s GIS. Collecting, analyzing, and visualizing spatial data has traditionally been complex, technical work that only trained specialists could do. Today, generative AI tools are at the brink of knocking those barriers down. Fast.

This raises some tough but necessary questions: What happens to GIS departments when users can do the basics themselves? What skills do GIS practitioners need to cultivate to keep up? And what can GIS departments build that AI can’t easily replace?

Which GIS tasks will users handle themselves with AI?

Traditionally, GIS departments and organizations have been responsible for a broad range of services: managing spatial data, running analyses, producing maps, and supporting decision-making processes. In the past, these services depended heavily on specialized software and deep technical knowledge, which, to a degree, protected a GIS team’s role in an organization.

Today, those barriers are rapidly falling.

Across the geospatial technology spectrum, AI is already supplanting human expertise. Generative models can automatically discover and organize datasets from public and private sources, a task that once took analysts hours of searching and cleaning. Data preparation—historically one of the most time-consuming aspects of any GIS project—is now being accelerated by AI that can identify errors, harmonize datasets, and even predict missing values with minimal human oversight.

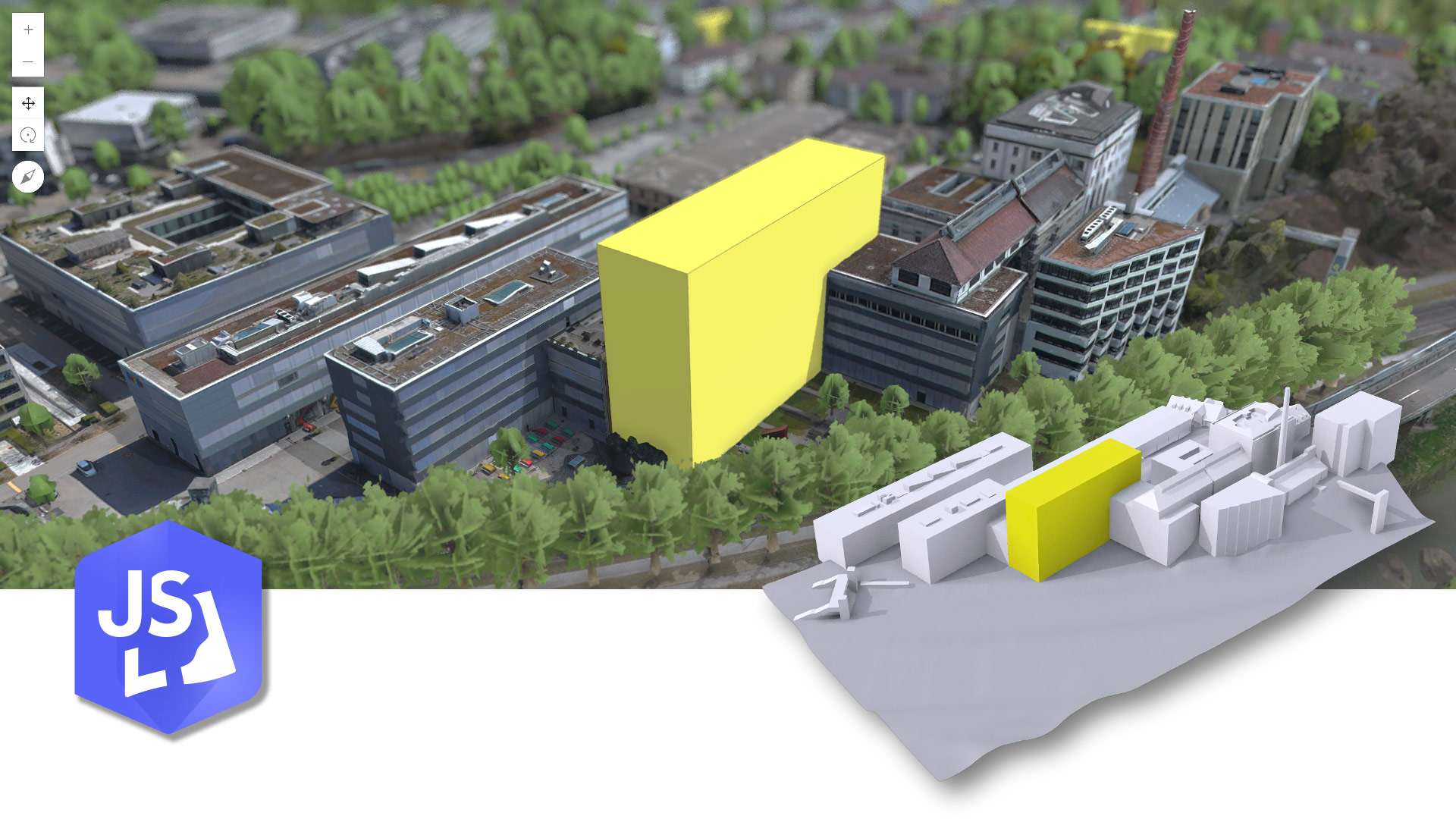

For instance, when an analyst needs to update a city’s land-cover map, they might spend days sifting through data portals, downloading files, fixing projects, and preparing data. With an AI agent, that analyst can search cloud repositories like ArcGIS Living Atlas of the World, on-demand Earth observation data from AWS, or Microsoft’s Planetary Computer to select the best imagery based on the project’s area and specific criteria, such as cloud cover and resolution. Once it identifies the appropriate data, it could manage all the tedious preprocessing steps, including cloud masking, band normalization, clipping, and projection alignment.

Another example: conducting a site suitability analysis. Traditionally, an analyst gathers data layers such as zoning maps, traffic flows, demographic data, and environmental constraints, then manually weigh these factors according to project priorities. After building weighted overlays and running spatial models, the analyst produces a suitability map. Instead of doing this manually, an AI agent developed with a tool like LangChain could handle much of the data planning and organization. It could then trigger a tool like PyLUSAT to run the suitability model. A user simply prompts the agent with a natural language request, such as, “Find the best location for housing based on proximity to transit and low flood risk.” And just like that, a suitability map is generated!

In other words, the services that users once relied on GIS teams to perform are increasingly available on demand, often at the click of a button. This means that, in the future, the real value won’t come from performing standard tasks faster. It will come from tackling the complex, strategic, and ambiguous problems that AI tools aren’t equipped to solve—challenges that require human judgment, contextual understanding, and nuanced decision-making.

Which skills does a GIS team need to evolve to stay ahead?

The shift in cognitive workload driven by generative AI doesn’t mean GIS expertise is becoming obsolete. It means the nature of that expertise is evolving, and quickly.

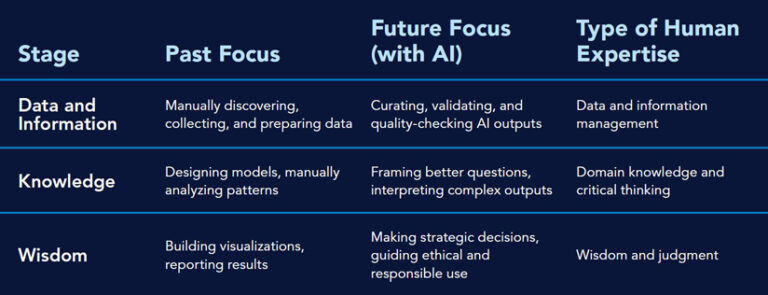

A useful way to understand this evolution is through the DIKW model: Data » Information » Knowledge » Wisdom.

At the base level, data is raw and unprocessed—coordinates, satellite imagery, and survey points. A step up, data is organized into information, like a shapefile showing flood zones. Knowledge builds on information by adding context, experience, and interpretation—for example, understanding not just where the flood zones are but why they matter to vulnerable communities. At the top is wisdom—that is, the ability to make sound judgments; anticipate consequences; and act ethically in complex, real-world situations.

For much of GIS history, professionals have operated primarily at the data and information levels. Finding, preparing, and analyzing spatial data has been where much of the value is created.

Now, AI is rapidly taking over those lower layers.

This means the future of GIS expertise lies in the more advanced stages, with knowledge and wisdom. GIS professionals will need to curate data, not just collect it. They’ll need to validate and question AI-generated outputs, not accept them at face value. They’ll need to frame problems more clearly; guide organizations through uncertainty; and connect spatial insights to real-world decisions that balance economic, environmental, and social priorities.

In practical terms, this means investing in higher-order skills:

- Critical thinking: Ask smart, strategic questions that AI can’t anticipate.

- Solution conceptualization: Develop use cases that address complex business uses centered around a geographic approach.

- Interpretation: Look beyond the patterns in the data to understand what they mean in context.

- Ethical judgment: Lead conversations about privacy, fairness, bias, and the responsible use of spatial data.

- Strategic communication: Tell compelling, clear stories that move decision-makers to act.

GIS departments that focus on higher-order skill sets will go from service provider to trusted partner. Instead of merely being asked to create maps and runs models, you’ll have the opportunity to engage in discussions earlier in the process. This engagement will help leaders understand which spatial questions are truly relevant.

Rather than just producing outputs for others to interpret, you will take on the role of guiding interpretation, challenging assumptions, and framing decisions through a spatial lens. As a consultant myself, I am often asked how to elevate GIS on senior leadership’s radar.

Perhaps AI will be the catalyst that makes this happen.

What assets can you build to enhance your ability to remain relevant?

As AI gets more sophisticated, GIS managers face a tough reality: Skill and expertise alone won’t protect your team’s relevance. To stay essential, GIS programs need to build assets that AI can’t easily replicate. Think of these assets as intellectual moats—durable advantages that protect your team’s value over time:

- Authoritative data: Most AI systems are trained on open, generic datasets, the kind of data that is readily available but often lacks depth, specificity, or context. These models are excellent at recognizing broad patterns, but they struggle when nuance matters—when small local differences, historical subtleties, or regulatory complexities change the meaning of spatial information. That’s why owning or curating high-quality, authoritative spatial data is one of the strongest moats a GIS department can build. It’s not just about collecting more data. It’s about creating datasets that are richer, more accurate, more timely, and more deeply connected to the realities of the organization or community you serve. For a city, for example, data reflects the local ground truth—not just current zoning maps but political forces that shaped urban boundaries. It weaves in domain-specific insights like how soil composition affects land valuation or how informal transit networks operate in a city. When GIS teams build and maintain these specialized datasets, they create a strategic asset that AI can’t easily copy or replace.

- Organizational fluency: Every organization operates within a web of political dynamics, cultural norms, legacy systems, and informal networks that aren’t written down in any dataset. They’re invisible, but they often matter more than the technical solution itself. AI might be able to suggest a supposedly optimal solution on paper, but it won’t understand the undocumented realities that determine if it succeeds or fails in an organization. GIS managers who know how to navigate those realities and understand where GIS can create real impact bring a kind of wisdom that AI can’t replicate. It’s not just technical expertise; it’s knowing how to make GIS matter in your specific environment.

- Creating and brokering GIS-AI agents and ecosystems: GIS managers who develop the skills to design, train, and orchestrate specialized AI agents (lightweight AI assistants built for specific geospatial tasks) will put their organizations on a very different footing. Instead of relying on off-the-shelf models that treat every organization the same, they’ll build bespoke AI ecosystems that reflect the unique goals, constraints, and realities of their environment. Imagine having agents trained on your spatial data and becoming the orchestrator of those agents to the extent that your team’s primary job becomes brokering an agent ecosystem—essentially a fleet of AI agents built to serve your business. And because these agents are trained on your organization’s own data, they get smarter and more aligned over time, evolving in a way that generic AI tools can’t.

The Risk of Standing Still

There’s a real risk here, and it’s not just about falling behind. If GIS departments don’t examine their strategy, they risk becoming irrelevant.

When users can generate their own maps, run their own analyses, and produce their own spatial insights without our help, the old service provider model simply doesn’t hold up. If the value you offer is limited to technical outputs, it’s only a matter of time before someone asks, “Do we even need a GIS team for this?” Staying focused on technical execution could result in a missed opportunity to lead and shape how AI is used.

The rise of AI marks a fundamental shift for GIS. It automates tasks across the entire geospatial data life cycle. It democratizes access to powerful analysis and visualization tools. It also changes users’ expectations about what GIS can and should deliver.

However, it doesn’t diminish the importance of GIS. It makes human GIS expertise more important than ever, as long as that expertise evolves.

The future belongs to the GIS programs that move beyond technical execution to strategic leadership. It belongs to the teams that invest in human skills, durable assets, and deep relationships. It belongs to those who are willing to ask themselves the hard questions now and act boldly on the answers.