Deep in a densely wooded state forest in Virginia lies the ghost of a once-thriving community named Lucyville. For decades, Lucyville’s story remained buried, known only from fragmented memories and scattered records. But thanks to the curiosity and dedication of a group of middle school students, Lucyville’s legacy is being rediscovered and celebrated.

Powered by ArcGIS StoryMaps, a history project on Lucyville has transformed a forgotten piece of the past into a living lesson in community and identity. The students at Cumberland Middle School in Cumberland, Virginia, created four ArcGIS StoryMaps stories to explore the community’s legacy and piece together Lucyville’s fragmented history and the lives of its residents.

A Forgotten Hub of Ambition

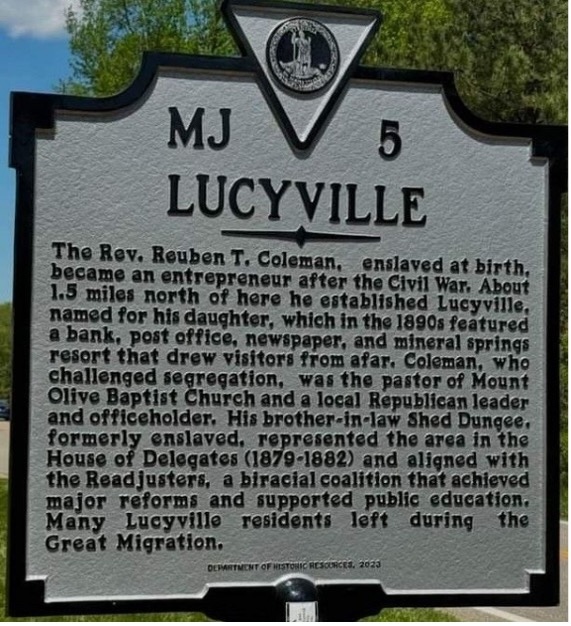

Founded around 1879 by Reverend Reuben Coleman—a man born into slavery and freed before the Civil War—the community was a testament to his entrepreneurial spirit. Named after his daughter, Lucyville became a bustling resort centered around mineral springs. In its 1890s heyday, it boasted a hotel, post office, bank, and even its own newspaper. It attracted Black and white residents as well as visitors from far and wide.

The community’s significance ran deep. Coleman, a respected pastor and local political leader, actively challenged segregation. As development and logging activities in the area expanded, Lucyville faded away, eventually becoming incorporated into Cumberland State Forest. Its story was gradually lost to time.

A School Project Sparks a Renaissance

The journey to rediscover Lucyville began a few miles away in an otherwise unlikely place: a middle school classroom. Lewis Longenecker, a history teacher at Cumberland Middle School, was looking for a way to engage his students beyond textbooks and standardized tests. An opportunity to connect students to history arose through a statewide Black History Month competition to propose new historical roadside markers honoring prominent Black figures.

Although some of his students’ initial proposals for figures connected to Lucyville weren’t selected, several students secured approval for a marker honoring Samuel P. Bolling—a politician, businessman, and formerly enslaved person who served in the Virginia House of Delegates. In a separate contest, another group got markers approved for Art Matsu, a football player and coach who was the first Asian American student at the College of William & Mary, and Kim Kyu-sik, a Korean politician and academic.

When state-sponsored competitions were discontinued, Longenecker, with the support of grants, decided to continue the work independently.

“There are a lot of historical figures here in Cumberland County who did a lot of really important things that should be recognized,” Longenecker says. “Those stories need to be told.”

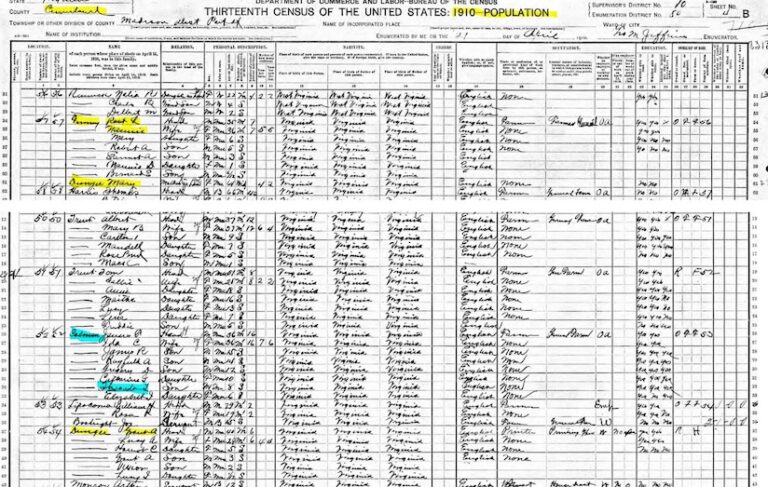

The project took on a life of its own. Students in Longenecker’s classes dove into the research, and they weren’t just completing an assignment—they were becoming historians. They scoured census data and analyzed primary sources from local archives. Their hands-on approach fostered a sense of ownership and pride, transforming abstract historical concepts into personal discoveries.

The Power of Storytelling with GIS

As students unearthed more information, they needed a way to synthesize and share their findings—this is where Annie Evans and ArcGIS StoryMaps entered the picture. Evans, director of education and outreach for the New American History project at the University of Richmond and a co-coordinator of the Virginia Geographic Alliance, has long championed technology as a tool for making history engaging. Having met Longenecker through a separate educational collaboration, Evans introduced him to ArcGIS StoryMaps.

Despite the challenges of working in a small, rural school district with limited resources—such as sharing a single classroom laptop to create the ArcGIS StoryMaps stories—students embraced the technology. ArcGIS StoryMaps provided an intuitive and powerful way to weave together narrative text, historical documents, images, and geospatial data.

“I’m not the greatest when it comes to technology,” Longenecker admits, “but [ArcGIS] StoryMaps makes creating presentations so easy, and it’s not that difficult for the students to learn.”

The students made four ArcGIS StoryMaps stories that viewed Lucyville’s history from several contexts, including the lives of key figures, the community’s layout, and its connections to other historical events. These ArcGIS StoryMaps stories, which began as school projects, became op-ed pieces published in the Cardinal News, a regional online news outlet. This helped bring the Lucyville story to a wide public audience.

The project was supported by Esri education experts and a variety of professional organizations dedicated to education and history. The Virginia Geographic Alliance, which promotes geo-literacy, provided mentorship and connected Longenecker with a GIS expert at Old Dominion University. The New American History organization, led by renowned historian Dr. Edward Ayers, provided a philosophical framework, championing the use of digital tools to empower students to become creators of history, not just consumers of it.

Reconnecting a Community

The impact of the Lucyville project extended far beyond the classroom. As the students’ research brought names and stories to light, they began to locate living descendants of the Lucyville community. Many of them were unaware of the full scope of their heritage, holding only small pieces of the puzzle—a photo album, a half-remembered story, a family cemetery plot.

“Until these middle school kids and their teacher put all these pieces together, they didn’t really realize how they were all interconnected,” says Evans.

These efforts culminated in the unveiling of a state historical marker for Lucyville in April 2024. The dedication ceremony was more than just a historical event; it was a massive reunion. More than 100 descendants of Lucyville residents returned to Cumberland County—many meeting for the first time—to celebrate their shared history. The students led site tours, sharing the stories they had found.

Inspiring a Generation

For the students, this project was a transformative experience. They developed critical skills in research, primary source analysis, and digital storytelling. They learned how to use GIS to visualize data and communicate complex narratives. More importantly, they discovered the power of their own voices and their ability to make a tangible impact on their community.

The Lucyville project is a reminder that history is more than a static collection of dates and facts; it’s an ongoing narrative that shapes our world. The students at Cumberland Middle School didn’t just learn about history—they uncovered it.

“If we can make history more interesting, engaging and personal, and local, kids will remember projects like this for the rest of their lives,” Evans says.

For more information about educational resources from the New American History project and the Virginia Geographic Alliance, contact Annie Evans at annie.evans@richmond.edu.

For teachers looking to replicate the success of the Lucyville project, Esri offers a wealth of free resources designed to bring geography and data storytelling into the classroom, such as the ArcGIS for Schools Bundle. To explore these tools and start bringing the power of GIS to pre-college classrooms, visit the Esri K–12 Education web page.